RE:NEW THE GLOBAL

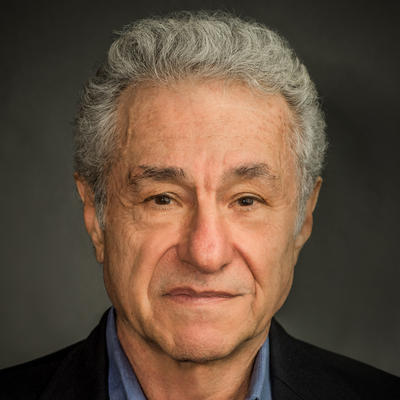

[00:00:07] Kurtis Schaeffer Good afternoon. I'd like to welcome you, everyone who's joining the second conversation in our two part webinar series, Re:New Democracy. I'm Kurtis Schaeffer, professor and chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia and co-director of the Religion, Race & Democracy Lab, which is hosting the event. I want to encourage audience members to engage in the conversation by raising questions throughout the program. Please use the Q&A function at the bottom of your screen. The chat and raise hand functions have been disabled. Our moderator and panelists will be able to see your questions and we'll answer them as they can. Also, we are recording today's webinar, as we did in our first event last week. The footage will be made available on our Web site, Religion Lab.Virginia.Edu, where you can learn more about the religion, race and democracy lab. And if you are interested in programs like this, our signature podcast, Sacred and Profane. The Religion, Race and Democracy Lab is pleased to host Re:New Democracy with the University of Richmond, Jepson School of Leadership and Wake Forest University's interdisciplinary humanities program. We opened the series last week with a conversation about democratic renewal in a local context. Today, a new set of conversation partners will address the challenges and possibilities of democratic renewal on a global scale. And now it's my pleasure to introduce our speakers. Gar Alperovitz has had a distinguished career as a historian, political economist, activist, writer and government official. For 15 years he was the Lionel Bauman professor of political economy at the University of Maryland and is a former fellow of King's College, Cambridge University, Harvard's Institute of Politics, the Institute for Policy Studies, and a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution. He is also the president of the National Center for Economic and Security Alternatives and is a founding principle of the Democracy Collaborative, a research institution developing practical policy focused and systematic paths towards ecologically sustainable, community oriented change and the democratization of wealth. Our next guest Sucheta Mahajan, is professor at the Center for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and a former chairperson of both the Center for Historical Studies and the Archives of Contemporary History at JNU. She has been Gillespie visiting professor at the College of Wooster, Ohio, a fellow of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, fellow of the Rockefeller Foundation's Bellagio Center, visiting fellow of the Trinity Long Room Hub, Trinity College, Dublin, and a visiting professor at the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme in Paris. Her significant books include Independence and Partition: the Erosion of Colonial Power in India, India's Struggle for Independence, and Education and Social Change. Her fields of interest spanned the short and long history of the 20th century. Its politics, political economy and social change. And the oral history of independence and partition. In recent years, she has been engaged in major south north multi-University initiatives on democracy, cultural trauma and global humanities. Now, if you were able to join us last week, you will have met our next two guests. So I'll introduce them more briefly. I encourage you to read their full biographies on our Web site. So up next, we have Corey DB Walker, Wake Forest professor of the humanities, who will serve as our moderator. And finally, we welcome Thad Williamson, associate professor of leadership studies and philosophy, politics, economics and law at the University of Virginia. And as I say, you're welcome to read their full biographies on the Religion, Race and Democracy website. Now, I will turn it over to our moderator, Corey Walker.

[00:04:23] Corey Walker Thanks so much, Kurtis. Good afternoon, everyone, and I'm so delighted that everyone has joined us for the second and our webinar series on re:new democracy. In our last gathering, we confronted the challenges presented by the ongoing crisis in democracy, the ongoing crisis of democracy in the United States with specific and sustained attention to the democratic crisis at the local level. While the crisis is broad and deep, we were inspired by ongoing efforts in the former capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, in creating a novel attempt to broaden and deepen democracy in its community wealth-building efforts. In many ways, Richmond embodies the promises as well as the perils of new efforts to renew democracy with a vibrant civil society that continues to push for more sustained cultures of democratic responsibility and democratic accountability across all sectors of society. But to think that democracy can exist only in America or in a vacuum outside of global trends is to not only state, the obvious is not, it's to miss, it's to unnecessarily draw rather our attention away from a broader, deeper crisis of democracy globally. Indeed, Melody Barnes, who joined us last week, reminded us of this when she underscored that the global democratic decline reported by Freedom House. Indeed, in their last report, Freedom House found that twenty five of forty one established democracies suffered overall declines over the past 14 years. Democracy is in retreat globally as we witness the rise of new authoritarian regimes and nominally democratic governments in the wake of the stresses and strains of conflicts over what should be an international consensus about how we should govern ourselves globally. And in a moment of global pandemic, economic collapse and ecological crises, we see an exacerbation of these democratic drifts globally. Today, I'm excited to have such Sucheta, Gar, and Thad with us to begin to examine this deep democratic deficit globally, but also to begin to understand how new openings may be presenting themselves in this moment of democratic decline. I'd like to begin with Sucheta, who joins us from New Delhi. Sucheta, democracy is in decline. You join us from the world's largest democracy. We've seen some of the challenges facing India. Challenges, some deep democratic challenges in our contemporary moment. Talk to us a bit about how you understand and analyze the current democratic crisis facing us globally.

[00:07:32] Sucheta Mahajan Thank you so much, Corey, for them and to the University of Virginia and to the religion race lab for having me here on this very important part of this very important conversation. I'm just, you know, as an introductory kind of statement, I thought I just flagged two issues. And then, you know, I take up some of the questions maybe later on. And so most of what I'm saying is going to be in the context of India. And I think that's why I'm here so that there is a voice from the global south, you know as it well. But before I take up the two issues that I wanted to take up, one was the shrinking of democratic space. And the second, the sharpening of structural inequalities. Let me just make a caveat. And that is I'm largely talking today about challenges to democracy in the context of the pandemic that we are facing. Because I think that is the one huge reality, which has changed just about everything right now in our lives. And here I thought, let me just make a proposition which would probably just set it out very, in the form of a kind of paradox that here we are today in a world where we are facing a global challenge by a pandemic and this global pandemic is being fought by democratically elected politicians, mostly on what we are told is a war footing in the so-called national interest. And at whose own? We are asked as ordinary citizens to sacrifice whatever we have left of our democratic rights. So I think this is a huge paradox that we're in right now. And, in India, what we are facing today is a huge shrinking of the democratic space. So much so that I think a claim like we're the world's largest democracy is something which sounds very hollow today in the sense it's just reduced to numbers. You know, number of people. Today we are facing an undeclared emergency. According to the Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders, there are so many such reports. But I'm just taking one of them, India stands at an appalling 142nd out of 180 countries in 2020. And we've fallen six places back since 2015. Yesterday, as I was just reading up for today's webinar, I came across a statement by 99 ex civil servants who had occupied the highest offices on the land who call this an undeclared emergency and they made a statement which civil servants, as you know, normally not want to make such statements. So I think it's very important where they called for adherence to the rule of law and they called for a nationwide movement to uphold the constitution, a constitution which for years radicals just, you know, dismissed as kind of a bourgeois document, which we really didn't care about. So what is this undeclared emergency we have? There is, of course, the usual blatant violation of liberties, drowning out of the voices of people. But what's different now is, and more dangerous, I would say, is that fighting this pandemic in the so-called national interest has become an excuse for further suppression of dissent. And indeed, even passing of restrictive laws. You will be shocked to know that the Epidemic Diseases Act, which has recently been invoked, goes back to the colonial era. It has not even been reformed at all. There are new labor laws on the anvil, which talk about twelve hour and six day weeks. Governments are going to be allowed. State governments can pass these laws now, which commentators have called going back to 19th century barbarism. Surveillance has crept in and this is all through the back door in the form of technology. It becomes mandatory, for example, to if you want to take a flight in India, you have to upload an application, which is ostensibly to mark the location of people suspected of having the Covid virus. But actually, it compromises your privacy. It's hugely unimaginable ways. So we have a situation to sum up this part, where normal political activities have just been suspended. You cannot even put up a placard to express your dissent. The state has gone on a witch hunt of so-called anti nationals, mainly Muslims, but also dissenters, critics, activists, students from my university, Jawaharlal University, which is one of the liberal universities in India, have been picked up for no good reason and slapped with charges of sedition. The head of the Delhi Minorities' Commission, you know, his his task is to look after the minorities interests, has been recently booked for sedition. I mean, the list just goes on. So shrinking of democratic space is the first important or the biggest challenge. And along with that comes that the the way in which a step, this democratically elected government that we have has adopted strategies to deal with the pandemic, which have exacerbated structural inequalities, whether these are along lines of class, gender, race, or in the case of India, religion based community. And you would be shocked to know, your audience would be shocked to know, that here, as Europe found its Jews, US has its Afro-Americans, in India of course, it's always the Muslims. Two hundred million Muslims have been the focus of anti-Muslim hate speech since the present ruling party came to power, and now this has just gone berserk. Muslims have being vilified in the social media. A leader from the ruling party, this is not some extremist right wing person, this is the leader of the ruling party, described Muslims as human bombs who are intending to spread the virus. Words like Corona-jihad, are being used in the media and emboldened by support from the leaders. There are, of course, extreme right wing groups, Hindu communal groups, who are going around beating and lynching Muslims and calling for their boycott. It's actually quite horrific what is happening and linked with this, of course. And I will end with this is, of course, what's happened to the poor. The poor, and this is where the class inequality, and its probably here where it's the most, the poor were most hit by the sudden lockdown; Four hours notice and we were locked down for two months and a survey done by a newspaper pointed out that 34 percent households in India could only last out for a week with their provisions and income. This was sometime in April. They would need assistance, but rather than giving them assistance, they... The entire media was full of what I can only call searing images of the long march home by these poor migrants, and they were beaten on the way by policemen. It was a criminalization of poverty, such as we have not seen in our lifetimes. My parents, who came as refugees at the time of partition from what is now Pakistan, used to talk about this kind of a movement and what it was. But here there is also state violence, you know, which is there along with it, people being mowed down by trains or just falling to the side of the road, exhausted, hungry, helpless. And of course, the contrast is with how people like us, the privileged, who are all over social media. Where people are just sharing posts all the time about NUE, about boredom. What? What should I see on Netflix? Oh, God. I have ran out of recipes for Far Eastern food. So this is the kind of inequality that we are facing. And we're talking about in this overall situation of shrinkage of democratic space. Thank you, Corey.

[00:17:58] Corey Walker Thank you so much, Sucheta. You really bring the democratic crisis to really to a point of sharpness and underscoring the ways in which we have the shrinking of democratic spaces. And in that shrinking, we see new authoritarian movements both by state as well as through civil society, by the mobilization of ethnic and religious hatred, and utilizing those ethnic and religious hatreds to consolidate particular anti-democratic regimes. And the sharpness of inequality, the sharpness of global inequality and inequality within societies really brings brainstorms, brings to the forefront the crisis of democratic governance and democratic possibility. I'm reminded that in India, Modi operationalize the lockdown in a few hours. And that left folks with just four hours and then left folks with no resources. And of course, the long march then enable the mobilization of different forms of violence both state sanction as well as informal sectors of violence. So democracy does ring a bit hollow when we use those empty phrases, "World's largest democracy", when democracy isn't real in the everyday. Gar, let me turn to you. We've heard from Sucheta on the challenges facing democracy in India. Begin to give us a way of thinking and a way of understanding our contemporary moment when democracy is on decline globally in the midst of a global pandemic. And how you begin to understand this particular moment that we're in.

[00:19:54] Gar Alperovitz Well, let me stand back and say I want to talk a bit about some positive things that are developing within the danger zone, within the threat and the dynamics between the two in the United States in particular. First, let me say I, as some of you know, I've been a historian of the bombing of Hiroshima, which is coming up, into the seventy fifth anniversary in two weeks. We have both not used nuclear weapons since that time, but also simultaneously there's been a massive, massive proliferation in an era when there have been authoritarian governments with those weapons and there are great dangers. I want to put that on the middle of the discussion. It often gets tossed aside. In the United States, I think what's striking to me is that there is on the one hand, the failure of the traditional social democratic structure, which is we call it liberalism in the United States, social democracy in Europe, which was a politics of balancing the power of the corporation and power of people like Mr. Trump with a politics significantly supported by labor unions all over the Western world, was a major institutional base for that politics. And it sort of kept the rough balance. In some cases, labor was 85 percent, as in Sweden, and you had a strong welfare state. I'm obviously oversimplifying. The United States had never reached more than 34 percent. It is now, that power base for a progressive politics in the United States is not 85 percent as it was at the peak in Sweden, not thirty four percent as it was here, but six percent and radically decline. So the institutional backing and people don't often probe to this. But we political economists and historians understand that without institutional power, politics is a weak, weak. a weak entity. That's very weak in the United States. And I think the election of Donald Trump is part and parcel of that weakness and that failing of the democratic process enforced by progressive institutional power. On the other hand, and I want to open this direction of things beginning to build in a new direction that offers some prospect and hope for the longer term. I'm a historian as well as a political economist, so I think it's useful to think in decade terms, although I've worked in House and Senate and at the highest levels of the US government as well. So I have a political near term as well as a long term view of this. But I would point out that there are new developments at the grassroots level. There is the Bernie Sanders movement, which demonstrated far greater progressive politics at the movement level. But there are also very interesting developments at the local level with that may speak some about this as well. What we're seeing all over this country and now in Great Britain and experiments in Denmark and in Spain of community wide ownership efforts which have a political economy powering, re empowering of the base of politics, in a way taking the place of labor unions as the institutional power base of a progressive or left politics. We're beginning to see that many parts of the country around a theme, and I think the theme is important politically and economically. But for those of you who want to know more about it, you can; the biggest ones are in Cleveland, Ohio, the evergreen cooperative structure, community wide structures of ownership in England. It's Preston. There's a very, very powerful examples there and many, many more on the Web sites we can give your attention to. But the building up at the community level of new forms of ownership, social development, ecological development reminds me very much of the prehistory of what became the New Deal in the United States, the development at the state and local level, which became enlarged in the Roosevelt administration to national politics and national policy. So the press doesn't cover much of this, but there's an extraordinary amount which the institute I'm associated with has been researching going on at the local level that I think offers hope in combination with the new movements. Now, I'm not pollyannic about this. I think Mr. Trump and also the forces he represents are very dangerous. But the longer term prospect is whether or not we can rebuild from the bottom up, not simply politically and not simply socially and not simply ecologically in terms of the movement's. But also the institutional structures that empower the John Kenneth Galbraith, the famous American liberal economist, 20th century economist, to talk about countervailing power, that the corporate dominated politics of the right needed to be countervailed not only through elections and democratic politics, but through institutional power. And in most of the advanced Western countries, that was labor unions empowering a progressive politics with the decline of labor here and even in Sweden, the most advanced of these, the reconstruction of new community empowerment, both economically, politically, but also morally, a vision of community as a guiding principle is beginning to be reconstructed at the grassroots level. And there are many experiments, if we have time to talk about, that are quite advanced, involving large scale ownership by workers and community in this country and abroad. And I see this viewing it as a historian, as a developmental trajectory, as the decay of the old political economic models fail. So I, and I want to set that set that as one part, the other, and I've, you know, spent a very good deal of time on foreign policy. American foreign policy has been constrained more and more in terms of having burnt the fingers of the policy makers on repeated war interventions that failed. We're seeing a great deal of posturing and there is a great deal of danger in the arms race. But I think it is fair to say, and most people don't realize it, the military budget is at a three to four percent level of the GDP in the United States, very large in the absolute. But very reduced in terms of the percentages. So the longer perspective that I want to offer, the consideration for this discussion is even as the decaying international posture of the American old interventionist war possibilities is decaying. And even as the labor union base of progressive politics is decaying, and even as the politics of a populists like Mr. Trump is faces us, is a danger and threat, simultaneously, there is the beginning of a whole new movements, both politically. And we've seen that in the Bernie Sanders movement and so in the ecological movement and the feminist movement, but also more important in some ways or equally important, new institutional forms. For the first time, we're seeing people talking about public ownership of the oil companies and taking them over. We're seeing community ownership, neighborhood ownership, municipal ownership in cities as far ranging as Detroit, Cleveland, but also in Boulder, Colorado. We're seeing experimentation not often covered by the press. Far reaching experimentation and new forms of democratic ownership, along with the political and moral reconstruction that you see in the Sanders move that the environmental movement and the feminist movement. So viewing it as a historian. The moment of Donald Trump is one thing and a very dangerous moment in this country. But on the other hand, there is a constraining possibility globally against interventionism. We've gotten our fingers burnt so many times on that. There's caution on the interventionist side. I hope. And on the other hand, a slow build up of the ideas, the institutions and the politics for a longer reconstruction of American politics. So I think we're in a very dangerous but also a period of possibility of the long haul. For those of who know something about our own history, the United States, much of what became the New Deal was actually developed in the 1920s and the prehistory of the New Deal in experimentation, that state and local level. And I think we're living in a similar period in the United States for what's happening at the grassroots level in terms of new ownership structure, ecological structures, solar development, vast range of developmental possibilities combined with the local politics that I see as the basis potentially. I'm no... no utopian, but potentially, there is a new building of power that I think can begin to lay the foundations for a longer term, a transformative possibilities. One last thing, odly we have noticed in the United States at moments of crisis, the last time in the great and the Great Recession, we nationalized General Motors, Chrysler, we nationalized AIG, one of the biggest insurance companies in the world. And so crises moments of potential major or minor semi crises also open interesting possibilities in this country. So I am worried about the immediate questions. Mr. Trump may act in an unruly way in this election. He is showing more and more signs of erratic behavior. But in terms of the longer term build up the country, I think there is reason to be hopeful about the direction of not only acknowledged politics and not only movements, but of institutional design. We posed with the question, and I think it is an exciting question as well as a daunting one. If the traditional models of socialism, state socialism and Soviet Union are faulting, if social democracy as in Sweden or even in the weak forms and in the United States and Great Britain is faltering because the labor union base is collapsing. And that's what's happening in both countries. Our own labor is down to six percent of the labor force. Sweden, it was at eighty five percent. What is the next the new system, the next society? And I think we're being the ground and the seedlings being built around these new community structures, the call for nationalization, which occurs and has occurred and is likely to reoccur, regional structures like the Tennessee Valley Authority in this country. I think we're seeing the laying down of ideas, experimentation, political movements that offer the possibility. Not more, but not less of the beginning of the foundations of a new direction for the country here. One would hope and certainly that is the direction I would urge we begin to pay attention to and work towards.

[00:31:04] Corey Walker Thanks so much, Gar. You not only point out that we are in a moment of democratic crisis, but in this moment there are openings that are opening up with folks who are working on the ground to exploit the fractures in our democratic culture and democratic politics to begin to think how do we begin to reconstruct society along new lines? How do we begin to develop responsive institutions that respond not only to our democratic deficits and our economic inequalities, but also to the highest aspirations we have as human beings and the highest aspirations for a new egalitarian society. You also remind us that the reconstruction of democratic, democratic possibility is not just built on the residue of the old, but more importantly, how bold we can face the new and willingness to experiment with new arrangements, new formations across all sectors of society. I want to turn now to Thad in order to get some intellectual, just to grab some intellectual understanding of this moment when in a certain way we can see that we have the emergence of new democratic possibilities and new understandings of democracy, so Thad in a moment where we see and witness a deep democratic deficit both within the U.S. and globally, but we also are witness to new possibilities of Democratic community emerging within the US and emerging in global society. How do we begin to make sense of this dialectic of democracy where we have this deep democratic deficit, but we have a renewed aspiration for a deeper democracy that even exceeds previous forms of democracy and responding to the highest aspirations of human possibility?

[00:33:12] Thad Williamson Thank you, Corey. And thanks again to the organizers of this, as always, Dr. Walker poses a multilayered, challenging questions. I'll do my best. I mean, I think the first thing to put on the table is that we do ourselves a disservice when we act as if democracy is an idea without enemies. Right. As if it's not a threat to certain people. And let me just break that down a little bit. I mean, I think when we talk about political democracy, people, you know, commonly reference, you know, four different aspects talk about representation. The idea that whoever is running the government should come from the people. Talk about accountability to the people. That is, you can't just do anything you want. And there has to be some structure making sure that what you do aligns with what people want. Thoroughly, we talk about empowerment, which is that anybody can have a voice. Anybody can raise an issue. And any time anybody can organize for change at any time, whether they're in power or not. And then lastly, we talk about governance, you know, providing basically the basis of order, but also addressing problems, our collective problems in real time. Well, if you look at the first three of those, representation, accountability, empowerment does all, are specifically democratic qualities that speak to the concept of political equality. And that's what defines democracy is this aspiration to political equality. But obviously, you can't have that unless you have two other things. One is a pretty robust measure, socio economic equality. Because people with vastly different levels of wealth and income are going to have different levels of influence and political voice. John Rawls, who his book is coming about 50 years old next year and maybe passé in some circles, his theory of justice, but still provides a lot of resources for working at out the internal connection between the idea of equal democracy and equal socio economic regimes. You really cannot have one without the other. And so the second thing besides socio economic equality is the idea of a robust public sphere and a public state, public spaces. But the idea that government can be a tool to advance the interests of people. OK. So, yeah, I think what we've seen in the US but to some extent globally is a kind of attack on that logic by people are threatened by these ideas. They see where they're going. They realize it if democracy truly builds a virtuous circle where a greater political empowerment is leading to a greater narrowing of the socio economic gaps. People of privilege want to stop at this, they have been in various ways, sometimes through racial and ethnic division, sometimes through an attack on quote unquote, the government. But it's been the last part in the most dangerous part for now is people pointing to the failures of governance, the fact that we're not solving our problems adequately, especially climate change. But many, many others. You know, the US has been literally a disaster in responding to Covid. People are looking at that governance failure and it doesn't necessarily go in a pro democratic direction in terms of the conclusion, it might go into authoritarian direction. Someone say, see, I told you this isn't work and provide a scapegoat, that they offer themselves, you know, or a sliver of restrictions on democracy as a way to solve the immediate problem. So, yeah, I think it's important to be aware of all those dynamics as we think through what it is to vitalize democracy. Says we're making sure yeah we have to solve the problems, but we have to do so a democratic way and not take the shortcut. And really, I think, you know, the intellectual discussion that is ongoing that needs to happen is there is one group of folks who think that trying to do a sort of a social Democratic restoration is the strategy. If we can go back to the 50s and 60s in the US context, when we had high tax rates and inequality seemed to be narrowing a little bit. If we can just recreate that whole picture, then we can get a handle on this. And there are others and Gar is a preeminent proponent of this. And I think quite persuasive is you can't reconstruct that world if you wanted to. And then our world was flawed to start with. Instead, we're in a world where we invent a new system of democracy in real time. And what's really hard is, is that. The urgent problems are right there in front of us, and anyone who gets even a snippet of power, whether it's a mayor or a president, is going to be, as some point, overwhelmed by the problems and consumed by them. Right, after you're in their office for a little while, you own it. And so we have to change our thinking and to think about how can we do systemic change over the long haul. So doesn't really matter who holds those offices? But but the progress is in the right direction. Because you have this idea that you're going to elect a president who's going to be a savior is, I think, misguided, and another one of the sort of false ideas need we to put behind us. So I hope that's helpful. You know, just just to put that on the table. But back to you. In simple terms, democracy has enemies because its internal logic is sort threatening of elites. And the situation that we're in now, we have to look to reconstruct a different system, you know, that is entirely new and obviously not ignoring the past or not taking the positive out of the past and present. But but but the system we need to create needs to be different in kind of what we've seen before. It won't be adequate to meet the actual challenges.

[00:39:08] Corey Walker Thad, I want to thank you for really bringing to the forefront the issue of democratic enemies within democratic regimes and how deep inequality within democratic regimes exacerbates democratic legitimacy. And as we talk about democratic deficits globally, we're also facing a legitimation crisis around democracy as an ideal and as a political form. And it's within the democratic... that legitimation crisis where we see new authoritarian regimes occupy space to provide individuals with safety and security, to assuage fears and to allay concerns. I'd like to move back to Sucheta on this simply because in your context in India, you're seeing the mobilization of these of new forms of hatred, of new anti-democratic forms of governance. Talk to us a bit about some of the opportunities that are, that are being mobilized by different communities. I know some of the work that you're doing at JNU really is geared towards building that next democracy, going deeper than just being a democracy, the world's largest democracy based on just a population figure. But actually going deeper. Talk to us a bit about some of the things that you see going on that are attempting to assuage this democratic crisis.

[00:40:48] Sucheta Mahajan Yeah, thank you, Corey. I thought some of the things that Gar and Thad and others made was so important, you know, to the discussion and as a historian, I think of the kind of I think rethinking that's been happening that I see around me is a lot to do with going back to our recent past, in our case, to our anticolonial struggle, which, apart from its anti imperialist orientation, was also a movement which brought about huge joining among the masses on all kinds of issues, you know. So from democracy through consensus, focus on civil liberties. A new kind of internationalism where Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to get up and go and fight in the Spanish Civil War. You know, that kind of, we have these cultural resources. We don't have to look towards the Greek pollice or to some other idea of direct democracy in practice. We have our own panchayats which are, you know, direct democracy and decentralized decision making, which are working sometimes not so well. But there's a whole system out there of governance, of self governance, with direct participation by citizens, which one can look at, recover, restore, etc.. So I think you would find it very interesting that even in very Left-Wing universities like mine, there is a rediscovery of Ghandi. There's a rediscovery of Tagore. There's a recognition, however, it's not so simple because in India, as you know, there are, we we our present is encapsulated at one moment of time, so many different stages of development, which other countries would have gone through, say, over centuries. So communism, regular kind of old style communism also thrives very well in one part of India, in like Kerala, for example. Which it would interest you to know, the only state in India with a communist government. It's run by it's called the Communist Party of India. Marxist, quite dogmatic, but they've done a fantastic job as far as containing the pandemic is concerned. And the health minister has been honored by the United Nations organizations, etc. But basically, it's an example of global best practice, you know. So it's, so we can't, like you say, the old type of socialism is over. No, it makes sense or it's making sense in certain areas. As I said, in other very creative spaces like the universities and at the community level, for example, what Gar talked about for, you know, in other parts of the world. But there's been a fantastic, again, I would say a flourescence of community level organizations and civil society movements, what are called youth social movements, not the regular style of institutional politics at all, but around issues around right to information, on right to food, right to employment. You know, these are very different kind of movements, which I've been. I wrote a book about one of them which was about, you know, right to education. And it was amazing, the woman who was behind this initiative. She was a political scientist at a university in South India. And she started this off. She was a she was a Maoist. She wrote her first book on Maoism. And she was you know, like a committed Maoist, almost. And she discovered Ghandi and self-sufficiency, decentralization, and most of all, working with nonviolence. And she built up at the grassroots level this, she was also the reason I'm talking about it, it is not just because I wrote this book on her, but she was the first PHD of our university, you know, so she's, she's one of us, you know. And later on, you know, her movement then became like best practice and development for the government and a National Commission for Protection of Child Rights was formed. So I think I would completely go with Gar in this that, you know, the reason we're here and we're talking is not because we are here to you know, we're only, you know, like steeped in pessimism. No, it's because of this excitement that there is the possibility that, despite being in these almost like, you know, you're facing a Leviathan kind of state sometimes or a behemoth. You know, it's huge. And you're worried and you're scared. And I you know, I personally have many cases against me in the university ect... I was thrown out of my chairpersonship for just opposing things. So we live in this world. It's tough, it's worrying, you know, ect. But what's happening around us and the kind of world we are part of, what we've been seeing, is just fantastic. How you know, how students, how teachers, how just ordinary people, the kind of tales of courage that comes. And as I said, the amazing cultural resources we have to fight this kind of Right-Wing Hindutva, this populism, the casteists, the whole thing that, you know, that edifice, this is there. But, you know, we have the resources and that's what, you know, being a civilizational sort of state, I think really helps over there. So we can we certainly see the light at the end of the tunnel.

[00:47:40] Corey Walker Thank you so much Sucheta. You remind us that the resources available to us don't just come from one place, but they come from many places. And these deep civilizational resources offer us new opportunities for democratic renewal in ways that we don't immediately think of. And these international dialogs really open up an understanding of the possibilities that are there. And no one possibility has to see all spaces. And, of course, the work in Kerala. I'm thinking of a good colleague there, Vijay Prashad at the Tricontinental, doing some great work there. So there's some opportunities that are always there. And Gar, I want to turn to you, turn to you with this. Sucheta has reminded us of the deep roots, deep democratic possibilities, deep democratic resources available to respond to this current crisis. You've made a book available in over the past two years discovered, articulating ideas around the Pluralists Commonwealth that can help us in this Democratic moment. Talk to us briefly about that project and how we can begin to revitalize and restructure democracy in the US. When we think of this huge space, this three thousand mile continental space and how we move forward to respond in our contemporary moment.

[00:49:13] Gar Alperovitz Well, let me just say that the book, we've made the book available free on our Web site; its called The Pluralist Commonwealth and the Web site, is the Democracy Collaborative. You can easily find it and you can get the whole book free. But what I do want to pick up and on what both of you have said and Thad has said and Sucheta particularly recently. At the grassroots level in the United States, there is an explosion of experimentation and of political action and of environmental action. The prehistory, the developing history of movements, but also worker owned companies, community owned development, land trust, neighborhood ownership, city ownership propqosals for Tate. And when in the last big crisis, we nationalize General Motors, nationalized Chrysler, nationalized AIG, which is the largest insurance company in the world. People don't realize an insurance company is a gigantic financial institution, like a bank, and they're minor crises like that. And there's a developmental process of great creativity of people involved, not only in politics, but in developing new institutions simultaneously and new environmental movements. So if you see this as a historical possibility, the the the wealth of experience being developed in activism, in experimental projects, some of them quite sophisticated. They're four or five hundred people working under community worker ownership in Cleveland right now. There are municipal takeovers in Boulder, Colorado. There are land ownership by neighborhoods in many parts of the country, the proposals for public ownership coming out. This is a very rich prehistory for the next larger progressive developmental thrust at that level. Viewed historically there are great dangers. Mr. Trump faces us with great dangers that could be violence and repression. Those are not to be ruled out, but at another level entirely. These are, the future sort of like a.. The emergence of a picture in a photographer's development. Slowly, you can see the image of new society beginning to develop at the grassroots level and at the activism level. So I am, I am not a utopian. The kind of fantasies that there are no struggles. I think we're in for some very dangerous periods before us. But there is also, I think, a building of power and ideas and politics and new list of things, new ideas about how to change the system. In practical terms, very practical terms at the local, regional, national, state at every level we're seeing developmental ideas emerging and organized activism as well. So I think the coming period of our, in America and also the simultaneous retreat from American wars abroad and in some imperial forms, I think there's some possibilities that a progressive movement of the real democratizing movement in Thad's sense of the word democracy is not beyond our possibilities. In any case, that's where the, where the emphasis and hope lies for the next period. I think.

[00:52:22] Corey Walker You remind us. I'm reminded that we're in a moment where both, Bernie, when we think of Bernie Sanders and the Sanders movement, we think of Black Lives Matter as a movement, beginning to really make some policy, some policy pressures throughout the US and its international ties, modes of new forms of solidarity that are really connecting these movements across nation states that does open up space for the expression of a new type of democratic politics. And even globally, we have Yanis Varoufakis and Bernie Sanders coming together and creating the Progressive International just launched in May. We'll see what happens with that going forward. Thad I want to talk to you a bit about some of your work and really how we can leverage all of these these new tendencies to begin to develop new and more robust policy frameworks, moral calls for democratic renewal that really are catalyzed and linked to new new ways of imagining community, new ways of imagining political subjectivity. Talk to us a bit about some of the work in which you're doing and really expanding the idea of community wealth building in a context, in a state, that has been in some ways, some significant ways averse to really novel forms of public policy that respond to the pressures of broader civil society.

[00:54:12] Thad Williamson Sure. Well, I mean, certainly, as we discussed last week, this incredible time to be a rich man, you know, to be America. In general and likely globally as well, we think about the bracketing that's going on with the Black Lives Matter Movement. And I think that's one of the things I learned from Gar a long time ago, that one aspect of the needed change has to be, for lack of a better term, a revolution in consciousness. Right, that people have to be able to see and imagine something different. And they have to be able to shed the way they've been taught to understand the past. And so I think you see now in this moment, especially with the younger generation, maybe even some older folks too, greater awareness and recognition and so much of what we have in America. And by extension globally or is based on vast historical crimes that we've inherited from the past. And we have enormous moral debts for the past. And that includes even some of Gars work on Hiroshima, where I was working with them when he published his book at the fiftieth anniversary. And there is, as he will no doubt recall, a lot of flack he got from challenging the conventional wisdom that many people were invested in. They weren't so much invested in the facts, the case. They were invested in the narrative of America's inherent goodness. Right. And so now I think we finally are at a point where we can cast away that claimed innocence and say, let's get real here. Let's be honest about our past, but also recognize the positive directories as well, the positive potentials and possibilities. And so I think to me wealth building for me is fundamentally a moral frame about how are we actually going to build something that's never been done before in history of humanity. Which is a truly equitable, multiracial, inclusive democracy that is also ecologically sustainable. Right. You know, and you pose that question it immediately merely becomes a global one because there's something to learn for everybody, because it, they're communities all across, you know, the world, that're taken on pieces of this. And so I think, you know, this conversation does have to be global and not just at the state level, but at the municipal level. And so what happened in Cleveland, you know, is informed by what happened in Mondragon in the Basque region of Spain, you know, 50 or 60 years ago. And now you have people from different countries wondering what's happened in Cleveland. And so I think if we can think of this as sort of a vast, global learning project in which nobody has determined an answer. But there are many, many avenues and possibilities to pursue. I think that's the right way to think about it. You know, as it is specifically the American context in terms of community wealth building, becoming that policy paradigm, as I said before, to say it a little more overtly. You know, I'm not against people invoking the New Deal as such. I usually know what they mean. It comes from a good place, but that's not literally what we want or the answer. We don't want the federal government being the only progressive actor in our system. We want to empower local communities to make their own decisions where we can actually have local activists come to table and help set the platform, help set the agenda based on their knowledge, of what's actually going on at the local level and then bring in their resources from the other systems to support that, as opposed to the bureaucratic Top-Down model that the traditional New Deal represents. So I think to me, wealth building is a way to flip American federalism in a way that's, both more democratic and I think also has a better chance of making traction on our problems. And I'm hopeful because I think regardless of which Democrat had won the nomination, all of them, including Mr Biden, if he should be elected president, is going to have to go in this direction because they're gonna find pretty quickly that they may be able to get because it's a crisis, be able to get some one or two big national reforms. But pretty soon, as the New Deal itself, they're going to run out political capital and it'll be limited in what they can do in terms of the massive federal transformation, you've got to be pushed on back to okay what can we do at the local state level? It's more strategic and use the dollars you have to try to see things that lead to bold or more radical steps at the local level. So I do think that we will see that playing out, hopefully and as soon as next January, if it takes a little bit longer, it takes a little bit longer. But yeah, I think the logic that we have to approach the problem that way is inescapable.

[00:59:05] Corey Walker Thanks so much Thad, you remind us of one of the key components and key principles that have undergirded our conversations, our two, two conversations around renewed democracy. And that key principle really is about creating a learning space, about democratic possibility that in this moment of deep crisis, we understand that the democratic deficits in the US and globally are broad and deep and they affect multiple sectors of society. But even in this moment of crisis, there are opportunities that we see, opportunities where individuals are moving and responding to the deepest high, the deepest and highest aspirations for human community and new ways, and in new manners, that really will enable us to not only meet the crisis both, but also to then build a new world. Last week I ended our conversation with Walt Whitman's, with a statement for Walt Whitman's Democratic Vistas. This week, I'd like to end our conversation quoting the words of our Arundhati Roy, who reminds us in this moment of pandemic that there is possibility. What that possibility is, we don't know yet, but we can walk through it together, together. And she writes, "Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine the world anew. This is, this one is no different. It is a port, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our databanks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly with little luggage, ready to imagine another world and ready to fight for it."

[01:01:12] Corey Walker I want to thank you Sucheta, Gar, and Thad for reminding us of this possibility. Let's go through the portal lightly. Let's go through the portal and struggle for a new world. Thank you and good afternoon.