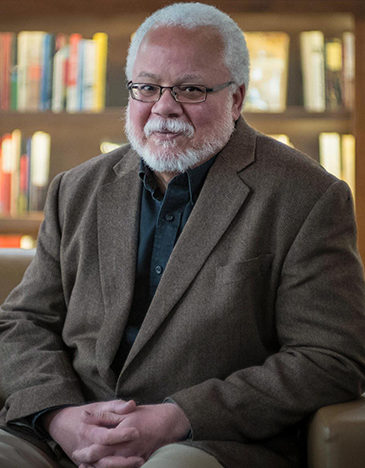

About the Lab

About

In the Religion, Race, and Democracy Lab, we explore big questions that concern us all. How have religion, race, and democracy divided us? How can diversity unite us?

No two aspects of modern democratic life bind us and divide us into groups more forcefully than religion and race. We see their impact everyday in the news and in our lives. But there is more to the story, and we want to tell it.

Stay connected as we launch a new website and our forthcoming podcast, Sacred & Profane, in Spring 2019.

Mission

The Lab supports teaching, facilitates research, and produces stories in many forms on religion, race, and democracy.

We bring researchers, students, journalists, and public leaders together to focus on the ways these complex forces are found in and shape our everyday lives.

We are committed to the idea that learning more about how religion and race work with democratic societies can help us to live together in today’s pluralistic and increasingly global societies.

Who’s Involved

The Lab provides a highly collaborative and creative research environment for UVA students, faculty, and journalists.

Students take courses on our topics, conduct sponsored research, and learn about producing scholarship for a broad public audience.

Our faculty Lab Partners develop new courses and host symposia on religion, race, and democracy, mentor students to become independent researchers and public intellectuals, and contribute to our podcast, Sacred & Profane.

The Lab’s professional staff produce our podcast, curate our website, and oversee our public programs.

Why a Lab?

A lab in the sciences tests hypotheses and discovers new knowledge. In a similar way, a humanities lab brings students, faculty, and staff together to investigate and solve problems collectively. The Lab runs on the conviction that new understandings arise when we bring the excellence of our different disciplines into a highly creative and collaborate environment. Working together, we are committed to producing engaging research that stimulates the public imagination.

Democracy Initiative

The Religion, Race & Democracy Lab is the first of several humanities labs that have been launched by the University of Virginia’s Democracy Initiative, an ambitious, interdisciplinary research and teaching enterprise to study how democracies have fared in their efforts to achieve legitimacy, stability, civil equality, accountability, prosperity, and resilience in the face of contemporary and past challenges.

A Common Thread

Research Samples

-

audio

Freedom’s Hat

Caleb Hendrickson: Chances are you’ve seen the U.S. Capitol building with its monumental dome hundreds of times even if you’ve never been to Washington D.C. It’s an icon, maybe the icon of American democracy. And the shape of the dome might be familiar from elsewhere. It’s modeled on cathedral domes, specifically St. Peter’s cathedral in Rome and St. Paul’s in London. Many mosques are also built with domes like these. Of course at the top of a cathedral dome you find a cross, and at the top of a mosque, a crescent. At the top of the Capitol dome there’s a statue of a female figure.

Caleb Hendrickson: She’s dressed in flowing robes and on top of her head…that’s what this story is about.

Caleb Hendrickson: Can you tell from here what’s on top of her head? Can you take a guess?

Interviewee 1: I’ve seen this statue in the visitor’s center but I can’t remember.

Interviewee 2: Looks like a vulture.

Interviewee 3: A rooster, or maybe an eagle?

Interviewee 4: Um, feathers? Yeah it just looks like feathers from down here. Inside we thought it was a chicken (laughter).

Interviewee 5: I would say one of those Roman helmet things with the ridge on it. I think she’s supposed to be freedom so I am thinking it goes back to Roman Greek, that kind of stuff.

Interviewee 6: There may be a symbolic meaning for this, but I don’t know it.

Caleb Hendrickson: The statue depicts freedom personified as a classical goddess. She’s standing on a globe inscribed with the words e pluribus unum. And yes, on top of her head rests a peculiar feathered helmet. This is the story of Freedom’s hat.

Vivien Green Fryd: I did not know the complexity of that statue when I started working on it. I had no idea that race and slavery were central to the statue’s iconography.

Caleb Hendrickson: This is Vivian Green Fryd, professor of art history at Vanderbilt University. She has written extensively on the art and iconography of the capitol building, particularly the Statue of Freedom, which was designed by the American sculptor Thomas Crawford in the years leading up to the civil war.

Vivien Green Fryd: He originally had her standing atop the globe of the world in order to show that the US’s Manifest Destiny was successful. She also was holding a sword as well as the American shield. And on her head, she was wearing what’s called the pileus or the Phrygian cap, which in English we call the Liberty cap.

Caleb Hendrickson: The pileus is a soft cone-shaped hat with origins in ancient Rome, where it was worn by liberated slaves.

Vivien Green Fryd: And when slaves were freed, the owner had shaved their heads, covered their heads with the cap, and then tapped them on the shoulders with what’s called the vindicta, and that becomes the staff with the cap on top is a symbol of liberty.

Caleb Hendrickson: Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy, was Secretary of War at the time the statue was commissioned. He had also been put in charge of the capitol’s extension.

Vivien Green Fryd: He objected to the Liberty cap, arguing, “Its history renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free and would not be enslaved.” Well that’s a really problematic statement because Davis was a plantation owner, a slave owner from Mississippi who argued on behalf of the slave system and the extension of slavery into newly acquired lands. So in making that statement he’s suggesting that the slaves on his plantation and on plantations throughout the United States are not human beings. They’re not people. He uses the term “people who were born free and would not be enslaved.”

Vivien Green Fryd: Crawford knew he had to change the cap.

Caleb Hendrickson: The capital’s engineer suggested replacing it with another Roman symbol, the helmet usually worn by Minerva, the goddess of the city and the goddess of war.

Vivien Green Fryd: So, the statue was a conflation of three very separate personifications. She’s a statue of America. She is also Minerva, the goddess of the war. And she’s Liberty. But what’s significant is the absence of the Liberty cap is the lightning rod of that work because it really all has to do with slavery.

Caleb Hendrickson: The Secretary of War rejected any work of art bearing any reference to slavery or to African Americans. While the building bears no visible trace of slavery, a great deal of its iconography depicts Native Americans, either as noble savages or obstacles to be conquered in fulfillment of the nation’s Manifest Destiny.

Vivien Green Fryd: The works of art on the building and inside the building establish an iconographic program that represents the subjugation of the native peoples.

Caleb Hendrickson: In this light it’s also significant that Crawford topped off Liberty’s new helmet with an imagined headdress, “inspired by the costume of our Indian tribes.”

Vivien Green Fryd: All these really conflicted issues about our nation are embodied in that statue.

Caleb Hendrickson: How are we to look at fraught images from our nation’s past? Thinking of them as sacred images of our civil religion might give us a place to start. These images command our gaze. We make pilgrimages to look at them, to come into contact with what they represent. But sacred sites are not sacred from the dawn of time. We imbue a place or an image with sacred meaning by the way we regard it, by the way we look, and the way we squint to make out its meaning. In the Capitol visitors center a small didactic panel tells some of the story we have just told. It begins to train the eye we bring to the icons of our conflicted past. How this eye learns to see and how it learns not to see will shape what the future of democracy looks like.

Caleb Hendrickson: Crawford’s Statue of Freedom was cast in 1860 in a foundry overseen by an enslaved laborer, named Philip Reed. Jefferson Davis left for Richmond not long after. He never returned to Washington he never saw the finished Capitol Building or the statue at its top. Neither did Thomas Crawford. At the height of his career, the sculptor’s sight began to deteriorate. He wrote to his wife of the tumor slowly darkening his vision: “The fact is t’is all in my eyes as yet. And I have not found any way so far of getting it out.”

Caleb Hendrickson is a doctoral candidate in religious studies. His work focuses on issues in religion, art, and visual studies.

-

audio

In the Halo of a Moment: Mira ji’s Life, Times, and Poetry

Meghan Hartman: Alone in a hospital room, with only a book as his witness, he finally got his wish: he died. As he had lay deteriorating, his body slowly turning in on itself, he would say to Akhtar ul-Imān, his dear friend, “ilāhi! Agar Mīrā jī ko sahat nahin ho sakti to unhen maut de de. Kam az kam isī taklīf se to nijāt ho jayegi.” “God, if Mira ji can’t have health, then give him death. At least he will be free from this suffering.” So God listened to him.

He died in the evening on November 3rd 1949 in the King Edward Memorial Hospital of Mumbai. He was 37. But, it is hard to be sure which suffering exactly Mira ji was referring to. Was it the crippling loneliness after nearly all of his friends had abandoned him? Or was it his fellow poets kicking him out of the literary circles which Mira ji had considered family, unlike the conniptive kinship tie of his brother who had long ago sold some of Miraji’s work to serve as packaging for veggies? Or was it the tumors enflaming his body? Or was it the doctors threatening to “correct” him with electro-shock therapy, straightening out a “seemingly” بھٹکا ہوا شاعر, a wayward poet as one biographer later dubbed him, rather unceremoniously? Or was it amorphous frustrations that to be different, to be queer, to write startlingly new poetry in a new genre, would just land you in the pits of ridicule?

Maybe all those painful questions pulsated as intensely as the tumors engulfing his body. But isī taklīf, this suffering. His emphasis on particularity, this, isī, a demonstrative so sure of a “here” and “now.” So completely confident in space-time, in the halo of a moment seemingly demarcating the past from the future, as if a moment were a forge between two mountains.

This suffering. This. Mira ji had spent a life time of writing Urdu poetry, crafting a new genre of long narrative poems called nazms, which would unmoor our faith in a clean definition of time and space, mixing up the chain of past-present-future, unsettling any reliance on chronology really. His nazms would always measure our measurements of time and remind us: what is a millisecond from a cosmic perspective? What is a second to a god? What does that look like?

So maybe, as he withered on the hospital bed with his book and shouted out to God to be free of this suffering, this actually referred to a moment which had accumulated other fossil-moments buried deep with memories not only belonging to him – but memories of other epochs, like the time of a pre-colonial India without British oppression, without British technologies of cruelty in the forms of outright massacres, or more subtly suffused in the syllabi of schools…or the time of Prince Siddhartha, poised to become the Buddha, which then wound up painted on the walls of the Ajanta Caves, which then trickled from the open veins of those living rocks into the eyes of Miraji standing before them, who then wrote a poem about it. Ajanta ke ghār, “The Caves of Ajanta.” Fossilized space-time enchanted Mira ji.

But all of this is not to say that Mira ji was an escapist or apolitical, though many of his contemporaries and biographers lobbed such insults. Mira ji was much more brilliant than he received credit for…he understood that he was a creature of his social environment as much as he was an accretion of multiple time streams coalescing in his body. So as anti-colonial efforts gathered more and more steam, but began to ring in monochromatic colors, Mira ji meanwhile was crafting his non-identity politics, his slippery dance between inter-temporal dimensions, first darting to the time of gods in Krishna’s Brindavan, then taking a pit-stop at the beginning of time. His resistance came in these subtler ways, etched into the scaffolding and themes of poems, or the resistance to succumb to simple definitions of identity…he was always pluralizing and specifying.

Perhaps that is why Miraji liked small words like (isī meaning ‘this’) or magar (meaning but). He liked small words because he saw worlds in them. Proliferating worlds saved from the brink of extinction, always a kaleidoscopic fervor. He once wrote this about a tiny little conjunction we call “but:”

“مگر۔۔۔ یہ مگر بھی عجیب لفظ ہے۔ میں سمجھتا ہوں کہ یہ لفظ بڑھتی ہوئی زندگی کی علامت ہے جہاں

ایک فقرے کی ہستی معدوم ہونے لگے۔ یہ مختصر سا لفظ اسے موت سے بچا کر آگے بڑھا دیتا ہے۔”

“But – this is a wondrous word too. I understand that this word [but] is a symbol of ever-expanding life where the existence of a phrase would begin to slip into extinction. This somewhat brief word saves the phrase from death and amplifies it.”

His jagged ending of a life cut short is – or at least I’d like to think so – is his version of a “but.” Though he died alone with only four people attending his funeral, his death has left him hanging in a wide open space, not exactly a void or an abyss, but a large expanse – the types of expanse he would write about in his poems, where you feel like the ecstasies of dissolving into a vital space, where breath and air start to merge. Though Mira ji lies buried somewhere in Marine Line Cemetery, he still speaks through his poems and essays. I would like to think that I can still hear your voice whenever one encounters the worlds you created in your poetry. One of your fellow writers once described your voice like this:

آواز بہت عمدہ اور بھاری پائی تھی۔ ریڈیو پر اکثر ڈراموں میں بولتے تھے۔”

“His voice had been rich and full of gravitas. On the radio he often used to perform plays.”

And another writer-friend wrote this:

میراجی گراموفون کی طرح بولتے رہے۔ یوں تو میرا جی کو گفتگو کا بڑا سلیقہ تھا۔ ”

“Miraji would speak like a gramophone. That was his flare in conversation.”

Mira ji, your voice still echoes in every present moment. We hear you.

Deep in the thicket of words, Meghan Hartman emerges. She can be found translating various Urdu, Farsi, and Sanskrit poems, studying furiously in the Teaching Assistant cubicles (aka the cubes) with her friends, and absorbing the various worlds of sound in and outside of her headphones. She also is pursuing a PhD in the Religious Studies department at the University of Virginia. Her dissertation will delve into the Urdu poetry and literary criticism of Mīrā jī, a luminous poet-philosopher of the twentieth century. When she does leave campus, Meghan can be found playing with her favorite four-legged friend Missy, performing sarcastic bits and sketches with her roommates, writing her own poems, or napping.

-

video

View Transcript

video

View Transcript

Reid’s Records

David Reid (owner of Reid’s Records): Well I mean, uh, back in the day we probably would have, I came back to run the store in the early 1990s. And I believe we had probably had about six or seven employees at that point. And we would have two cash registers going and people would be coming in every Friday after work all through the weekend.

We had tickets for all kinds of concerts, and you know, Reid’s was kind of like the happening place for all the newest music that’s coming out. When people were dependent on actual physical product. So we were bustling.

Christmastime probably would be the busiest time of year. I mean we’d just be from start to finish from sunup to sundown, we would just be swamped in here. People coming from all over the Bay Area. I think Reid’s (sigh), I don’t think Reid’s is so much, uh, critical to Oakland or to Berkeley or the Bay Area. I think Reid’s story is mostly one of longevity and service. And that a black enterprise can thrive and be supported by the black community, not being reliant on any other. Because I mean if it wasn’t for African American clientele here, Reid’s would not have existed, and it would not exist today.

I mean I was, back in the 90s, I was like the number one choir robe seller for Murphy Cap and Gown in California. And, I basically had no white choirs ask me for robes. I mean they wore robes, but they tended to gravitate to where they wanted to gravitate. So its always been probably 98 percent black clientele that have supported this store for 74 years and I think that’s, that’s, to be commended not by Reid’s, but by our community.

The neighborhood in the last, I would say, oh goodness since the probably mid-90s has changed dramatically. South Berkeley was basically a black enterprise zone, and a black, basically black neighborhoods. And it has changed, gentrification has taken over. All the most main black businesses have gone and have been replaced by housing or were just not replaced. So it’s kind of like the area has gone the way the demographic has changed. Berkeley, South Berkeley, is no longer mainly a black neighborhood anymore. It’s like I said, it’s been gentrified. So there is very few black businesses here that was left.

Back in the day we had doctors and lawyers and restaurants, of course pool halls. I mean there was things going on up and down the street 24 hours a day. But now it’s become very quiet. And culturally very sparse.

My prayer for future generations is to not make the mistakes, to allow the same things that happened to you that have been happening to my generation and generations previously. African Americans, I know we’ve achieved a lot of things in a lot of ways but, it’s with gentrification, there’s no where you can point where we are. I mean if you go to any city nowadays and you go to look at Martin Luther King Boulevard, there’s none of us there. We don’t live there anymore. It’s like a tombstone. This is where black people used to be. And I think that’s a tragedy.

Paige Taul is an Oakland, CA native who received her B.A. in Studio Art with a concentration in cinematography from the University of Virginia. She currently attends the University of Illinois at Chicago for her M.F.A. Her work focuses on themes of blackness in relation to self and family.

Who's Involved

In The News

Get Involved

Learn about forthcoming podcast episodes, newly published projects, research opportunities, public events, and more. There’s a lot in the hopper—stay tuned for the launch of the Lab’s robust website filled with dynamic multimedia, including our first season of Sacred & Profane, coming spring 2019.