[00:00:00] Kurtis Schaeffer I'm Kurtis Schaeffer

[00:00:01] Martien Halvorson-Taylor and I'm Martien Halvorson-Taylor. And this is Sacred and

Profane.

[00:00:08] Phil Woodson Good morning.

[00:00:08] Crowd Good morning.

[00:00:13] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Not long after sun up on a typically humid day here in

Virginia, a group of 25 or so people gathered in downtown Charlottesville right in front of the county

courthouse. Our colleague Jalane Schmidt was there that day. She's a professor in the Religious

Studies Department here at the University of Virginia.

[00:00:34] Phil Woodson Jalane, hello.

[00:00:39] Jalane Schmidt And I do a lot of public history projects in the city of Charlottesville,

Virginia.

[00:00:45] Martien Halvorson-Taylor If Jalane sounds a little distant here. That's because we're

social distancing. Since we can't meet indoors these days, we reached her at home by phone. But

let's get back to the story.

[00:00:58] Jalane Schmidt I was there, the Bible study, which was led by two activist pastors, Phil

Woodson and Isaac Collins.

[00:01:06] Isaac Collins Why are you here so early in the morning? (With crowd) This spirit has

called us here to tell the truth. This statue is an idol to white supremacy.

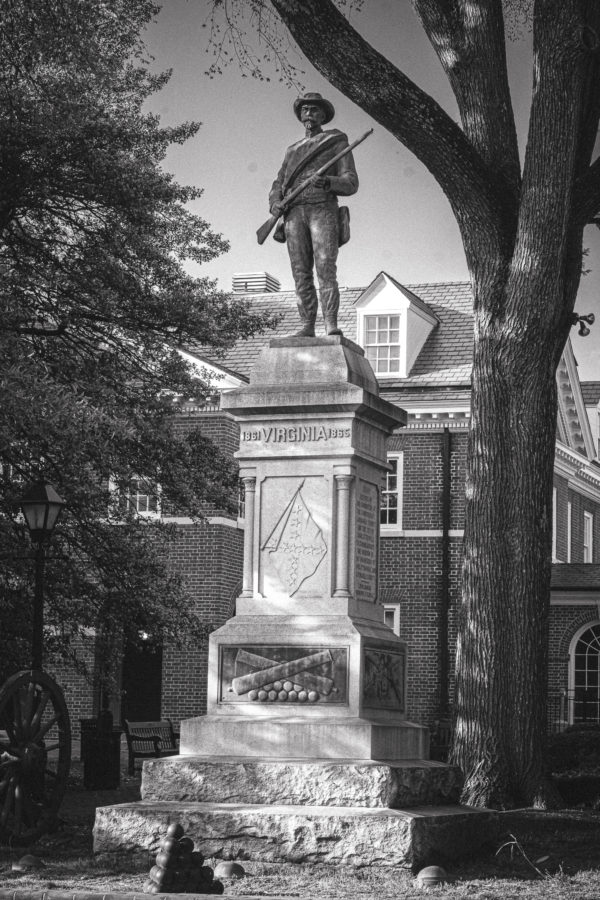

[00:01:22] Kurtis Schaeffer That statue they're gathered in front of is known as Johnny Reb. It's a

bronze statue of a soldier with a rifle in his hand ready for action. On his belt buckle are the initials

C.S.A. That stands for a Confederate States of America.

[00:01:39] Jalane Schmidt And this was one of the first of three Confederate statues to go up in

downtown Charlottesville. Johnny Reb has been standing in front of the county courthouse since

1980; it got paid for with money raised by a local chapter of United Daughters of the Confederacy.

[00:01:55] Kurtis Schaeffer In the decades after the Civil War, hundreds of Confederate statues

went up in towns across the United States. Most are in the former Confederacy, but a total of 31

states across America, including California, Washington and even Illinois, the land of Lincoln, put

up some kind of Confederate monument.

[00:02:15] Jalane Schmidt The soldier in front of the Charlottesville courthouse was mass

manufactured outside Chicago and sold all across the country. Depending on the town, they just

added a belt buckle that read “USA” instead of “CSA.” They're kind of a generic image, like a cast

bronze G.I. Joe.

[00:02:35] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Besides the belt buckle, there's another detail that stands

out. Carved into the granite plinth, holding up the statue, is a cross formed by the 13 stars of an

artfully draped Confederate battle flag.

[00:02:55] Jalane Schmidt And that cross, it’s at the heart of what we're going to talk about today,

because as much as these monuments are idols to white supremacy, they're also steeped in

Christian tradition. They were placed in public spaces with the full support of white church leaders

and congregations. And at that Bible study, Reverend Isaac Collins talked openly with his

congregants about those links.

[00:03:20] Isaac Collins We're not used to thinking about these statues in religious terms. And yet

when you look at the history of their installation and the ceremonies that were held at the time,

there were pastors there. There were prayers that God has invoked repeatedly. It's really about a

theology, one that's become less explicit in our day. Yeah, I mean, there are literal angels guarding

the path of Stonewall Jackson over here. We realize that there are spiritual arguments for why

these things should come down, not just political or historical, but spiritual as well, and we feel like

as pastors in Charlottesville, we've kind of inherited that legacy and we wanted to respond to it.

[00:04:00] Kurtis Schaeffer Jalane, you've been giving tours of the Confederate monuments in

downtown Charlottesville for a few years now.

[00:04:06] Jalane Schmidt Yeah, and I'm not giving the tourism bureau type tour down there. I

started giving these tours during the summer of hate during this summer of 2017 when there were

lots of journalists who are coming to town in Charlottesville and wanted to know the background of,

you know, why there were so many statues in our town and what they stood for.

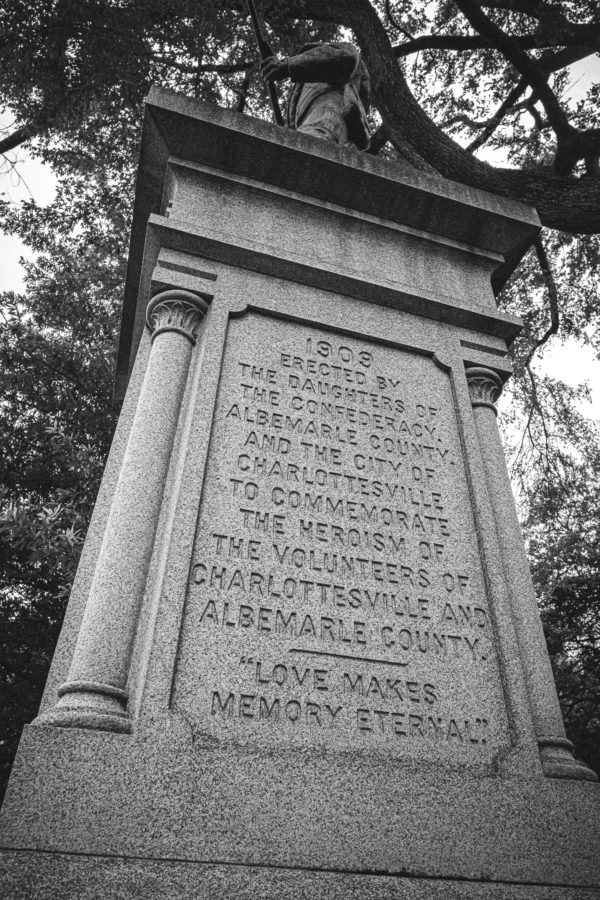

[00:04:28] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So you had an idea of where to go to explore the religious

ideas that lie behind these statues. You took us on a tour a few weeks ago to look at yet another

Confederate monument in Charlottesville. This one is in a cemetery on the University of Virginia's

campus. And it went up even before the statues downtown.

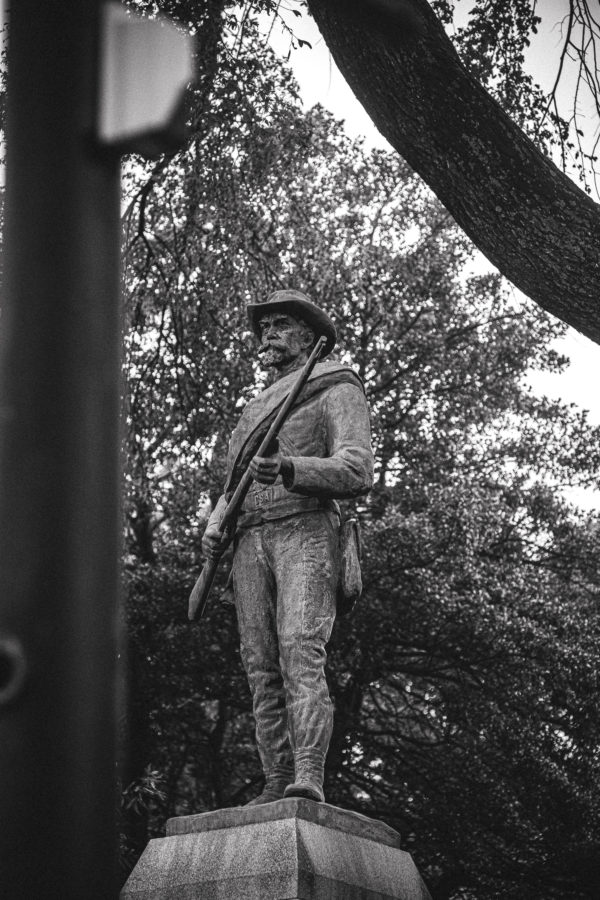

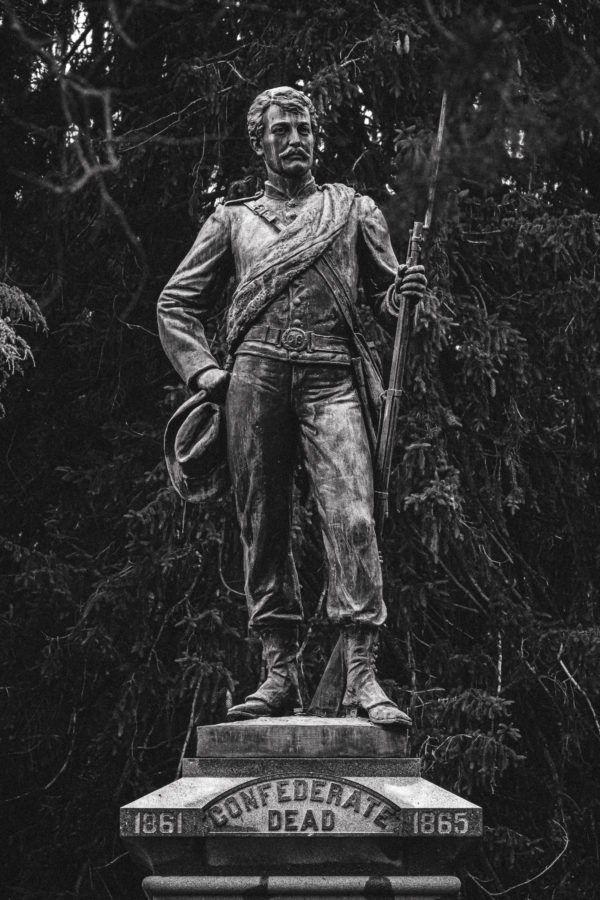

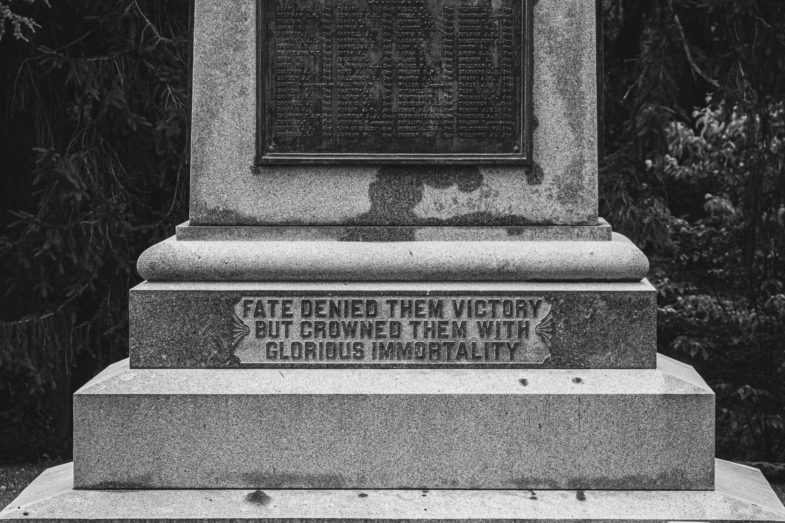

[00:04:54] Jalane Schmidt Yeah, well, it kind of does escape notice. You know, for a lot of people,

it's just kind of tucked away. If you weren't coming and looking for it, you probably wouldn't see it.

We're standing here and we've got a, you know, a granite plinth here. It's about ten feet tall. And

then on top of that is a bronze figure of a Confederate soldier, about eight foot tall. It says

“Confederate dead.” And then, “Fate denied them victory, but crowned them with glorious

immortality.” This is the first Confederate statue that was installed in town. Most of the first

Confederate monuments that were installed - and this is all over the South - were put in

graveyards. They were objects of memory, memorialization of mourning at the dedication

ceremony.

[00:05:52] Kurtis Schaeffer At the dedication ceremony, veterans gathered with the families of

soldiers killed in the war. Locals, including faculty from the University of Virginia, attended too.

Music was played, wreaths were laid, speeches were read, including a formal dedication by a

veteran who'd served alongside Lee.

[00:06:12] Jalane Schmidt The veterans themselves are dying off, so there's a lot of concern, you

know, to educate the next generation of white Southerners.

[00:06:25] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Before the war, Southern whites were frank about their

reasons for creating a new government. Take James Holcomb, a law professor here at UVA, say

he quit his job at the university in 1861 to advocate for Virginia's secession.

[00:06:45] Reader (James Holcombe) The institution of slavery is so interwoven with a whole

framework of society and a large portion of our state and constitutes so immense an element of

material wealth and political power to the whole Commonwealth, that it's subversion through the

operation of any unfriendly policy on the part of the federal government would, of necessity, dry up

the very fountains of our public strength, change the whole frame of our civilization, and inflict a

mortal wound upon our liberties. And if there is danger to an interest of such importance - serious

danger, although remote - there can be no higher duty which any Christian or any patriot owes to

his country than to resist it in its first approaches.

[00:07:33] Jalane Schmidt So, in the minds of these confederates, the antebellum South was an

ideal Christian society, a benevolent, paternalistic hierarchy, and one that was ordained by God.

Just as God looked over his children on earth, Southern slaveholders imposed order on their

households.

[00:07:51] Kurtis Schaeffer That kind of paternalistic idea of slavery as a Christian institution

endured after the war. Even as veterans and their descendants began to cloak the reasons for

secession and more acceptable language. It had never been about slavery at all. Rather, it was

about states’ rights. Or if slavery was a part of it. It was only because slavery was the most

humane option for a people who could not be trusted with their own freedom. Speaking to a

reporter from the New York Herald in 1865, Robert E. Lee had this to say: "Based on wisdom and

Christian principles, you do a gross wrong, an injustice to the whole Negro race in setting them

free. And it is only this consideration that has led the wisdom, intelligence and Christianity of the

South to support and defend the institution up to this time." So in other words, Lee was insisting

that far from being cruel. Slavery was a Christian institution in the best sense.

[00:08:49] Jalane Schmidt Even after the end of slavery, any sort of change to this God ordained

racial hierarchy justified violent opposition, and especially the notion of citizenship and rights for

the descendants of enslaved people. At ceremonies held in the shadow of Confederate

monuments. There were very pointed calls for black people to stay in their place.

[00:09:12] Reader The war brought out in the Southern slaves traits of character that call for

recognition, their loyalty to master and mistress, their fidelity, watchfulness and courage were great

and most surprising.

[00:09:25] Jalane Schmidt That came from a 1915 speech, a local pastor game at a Memorial

Day ceremony on this very spot in the University of Virginia's Confederate cemetery.

[00:09:37] Reader The teachers of the Negro race, if they would find the best possible exemplars

for their pupils, should themselves study the character of the Southern slave of the war period and

portray the same as clearly as possible. And now let us bow our heads.

[00:09:57] Jalane Schmidt And this is at the heart of the Bible study I went to downtown. It was a

recognition of the intersection of white supremacy and white Christianity in the South. There's this

idea that the old south was also a more Christian place. And that was something that the men and

women who maintained Confederate graveyards were very clear about from the beginning. Take

that pastor who spoke earlier.

[00:10:23] Reader While loyal to the country as she now is. We will say concerning our beloved

Confederacy, if I forgive thee, old Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not

remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth. Without disloyalty, you may

substitute Confederacy for Jerusalem.

[00:10:44] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Jerusalem in Christian theology is the holy city, the center of

the world where God resides, evoking the earthly and the heavenly. Is it this kind of religious

language and symbolism to describe the Confederacy that gives these monuments a kind of

pernicious traction?

[00:11:05] Jalane Schmidt Yeah, and particularly that and then the combination with of other

esthetic tropes like Greek allegorical figures of valor and faith - you know what I mean - that are

just kind of completing this neoclassical tableau really lends the power to it. And, you know, many

of these gatherings that took place there with the benediction of these pastors.

[00:11:37] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So as we were leaving the UVA graveyard, Jalane, you

showed us something just outside the wall that goes unmentioned in all of these ceremonies.

[00:11:49] Jalane Schmidt Yeah. We are outside the walls proper of the cemetery here.

[00:11:55] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Dozens of unmarked graves where the enslaved men,

women and children who worked to build and maintain the university were buried.

[00:12:09] Jalane Schmidt These black graveyards were regularly raided by so-called

"resurrectionists," as they were called. And these were people who were hired by the university

medical school to procure cadavers and to transfer them to what's called the anatomical building.

Remember that? I mean, the Confederates that are buried in their quadrant over there are being

guarded, as it were, by the Confederate Soldier Monument that's, you know, on a pedestal,

standing guard, standing sentry, making sure that they're at rest, that they're remaining at rest. But

meanwhile, over here on the other side of the wall of the cemetery, these graves are being

subjected to being robbed, to having the bodies disinterred, to be dissected by U.V.A. medical

students. And effectively, you know, as Justin Greenley has said, you know, that people are being

enslaved after death.

[00:13:10] Martien Halvorson-Taylor It's a powerful reminder of how these markers get used not

only to promote one version of history, but also to suppress others.

[00:13:19] Jalane Schmidt Exactly. And again, if you consider the fact that the outright majority of

residents of the city of Charlottesville and Albamarle County between 1820 and 1890, the outright

majority were African-American; till 1865, the majority of residents were born slaves. So, yes, I see

these these Confederate monuments, they're actually doing a lot of work to quash memory. It's a

very kind of public facing assertion of what should be taught to the young. You know, what the

public is supposed to remember.

[00:13:52] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And that's why these statues end up not just in religiously

symbolic places like cemeteries, but in public spaces like the Johnny Reb statue in front of the

courthouse where we started our story. Even in that more secular space, we can still see how

white Christian institutions intersect with white supremacy. In the 1800s, the courthouse served as

a meeting place for many Christian denominations. Thomas Jefferson attended services there,

calling it the town's "common temple." And, it was also a place where contracts were filed and

estates were settled and therefore a place to do business. Before the war, in Charlottesville, a lot

of that business was buying and selling black men, women and children. That included members

of the Gillette, Granger, Hubbard and Hern families, 33 of the over 600 people that Jefferson

enslaved at Monticello over the course of his life. Three years after Jefferson's death, they were

sold to pay his debts just a few yards from the courthouse where he and other white citizens

worshiped. For many years, the only sign of that history was a small brass plaque embedded in the

nice brick sidewalk just a few yards from the courthouse and the statue of Johnny Reb. Unless you

knew the brass plaque was there, you could miss it entirely. You could walk right over it.

[00:15:47] Isaac Collins Churches, you know, all over the country and especially over the south

have not dealt with the legacy of the people who abandoned them and what they've done. And

actually, you know, when I talk to congregants or people that come to the study about that, often

time there's that there's a fear, right, of condemning their parents who believed in segregation or

their great grandfather who fought in the civil war. You know, what do we do when these statues

are somehow them talking about them in this way? This notion that we just have to maintain the

past instead of trying to repair the past or improve in the past makes them feel like they're also sort

of condemning their families. You know, Christianity is about transformation. And so, when we

when we feel when we feel as a church that maybe it's best to kind of let things be, then we're not

really practicing the faith that we proclaim.

[00:16:49] Martien Halvorson-Taylor A few weeks ago, the Bible study met again. It was a very

different feeling than the quiet gathering on a Saturday morning the year before.

[00:16:58] Phil Woodson Good evening. This tiny toy bullhorn my wife got me is working out

great.

[00:17:04] Martien Halvorson-Taylor That night, the square was full.

[00:17:08] Phil Woodson My name is the Reverend Phil Woodson, I’m the associate pastor at

First United Methodist Church. Just a few housekeeping issues before we begin…

[00:17:17] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd at the

hands of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin had been going on for weeks.

[00:17:25] Phil Woodson I want to announce, if you've been out in the streets and have you been

protesting, well done. Make sure you're wearing masks. We've been talking about wearing

glasses.

[00:17:34] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And in Virginia, protesters have taken on Confederate

statues once again as tangible symbols of white supremacy. Protesters in Richmond have torn

down three Confederate statues in the heart of the city and the governor has promised that a

multistory statue of Robert E. Lee will be removed as well.

[00:17:58] Isaac Collins We talked about these idols, these statues as idols for white supremacy,

but the truth is that when they are gone, the work will not be finished. These statues are the

heroes. They tell the story of white supremacy in our community. They are meant to terrorize

people that don't look like this and they are meant to valorize the people that do. White folks,

nothing less than our souls is at stake in this fight. Nothing less than our very humanity is on the

line. And it starts with embracing Christ’s call to completely transform the way this society is built. It

is time for our community to imagine the anger of our black brothers and sisters and join them in

the call to defund the police and dismantle our existing criminal justice system.

[00:19:07] Kurtis Schaeffer Jalane, as we record this, so much is happening in the state of

Virginia and in Charlottesville with the statues. Can you tell us what's happening right now?

[00:19:18] Jalane Schmidt Yeah, well, in Richmond, these statues are coming down almost on a

daily basis it seems. The mayor of Richmond, Levar Stoney, has declared that the statues

constitute a public safety hazard, so he has directed that they be taken down. And so just an hour

ago, they took down the soldier and sailor monument. Richmond's landscape is changing very

quickly right before the residents' eyes. It's different here in Charlottesville, where the two big

statues of generals, Lee and Jackson, are still standing because there is an injunction and the city

has filed a motion with the Supreme Court to have that injunction dissolved. And the county has

just announced their process is moving forward to consider what to do with Johnny Reb. So, there

are you know, there are definite steps that are being taken in both the city and the county toward

removal of our local statues, but it's not anywhere with the same pace as what is going on in

Richmond.

[00:20:18] Kurtis Schaeffer The statues may be symbolic, but they're invested with intense

emotional energy and they have been for the entire time that they've been standing. What do you

think is going to happen with that emotional energy when they're gone?

[00:20:37] Jalane Schmidt Wow, that's a really good question, because already we're kind of in

this interim time where we're waiting, we're waiting, you know, as we're recording this in the

summer of 2020, you know, we're looking forward to perhaps September, October, that these, you

know, that finally these statues will be removed. What's happening right now is there are actually

armed neo-confederates that are in our parks every night at the least, actually at the Jackson

statue and in their words, guarding the statues, you know, and sometimes accosting passers-by

and this sort of thing. So where does that energy go? Well, right now, you know, we're seeing

people, you know, kind of show up with a better kind of instilling some fear. You know, they have

their own fear and turmoil about what they say, what they see as their history being taken away.

And they are projecting that outward, you know, onto the community, onto passers-by in the parks.

Hopefully, you know, a lid will be kept on that and we’ll move forward with removal. I mean, in

Richmond, there hasn't been people showing up with arms, you know, to oppose the workers who

are taking down the statues and hopefully that will be the case here in Charlottesville

[00:21:49] Martien Halvorson-Taylor: If we've been talking about these monuments as symbols of

white supremacy intersecting with Christianity. What is the challenge that is being meted out to

Christianity with the removal of these symbols?

[00:22:06] Jalane Schmidt: You know, there's been a lot of talk about how, relatively speaking, it's

easy to take down a statue. But what's difficult is to take down these systems of white supremacy

that have been put in place brick by brick, you know, over the decades. What would it mean to

dismantle systems of oppression, say, in education, in health care, in the criminal justice system?

That's the real work that needs to happen. I'm concerned that there might be a sense of that taking

down these statues means that the work is done when really it's just beginning. That's just that the

statues were a very tangible material marker of white supremacy. But we still need to dig into the

systemic systems of white supremacy.

[00:22:52] Isaac Collins: Why are you here so late in the evening? (With crowd) The Spirit has

called us here to tell the truth. This statue is an idol to white supremacy. We have gathered here to

reckon with the full history of Charlottesville’s past. (Without crowd) I do not believe you. Can you

talk about this like you believe it? Let me hear it again! (With crowd) This is our community and we

do have power! We have power to plant seeds of justice! We are united!

[00:23:38] Martien Halvorson-Taylor: Sacred and Profane was produced for the Religion, Race

and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia. Our senior producer is Emily Gadek. Our program

manager is Ashley Duffalo? Kelly Jones is the Lab’s editor. Today's story was brought to us by

Jalane Schmidt. Special thanks to the Reverend Phil Woodson and the Reverend Isaac Collins.

Thanks also to Mary Gardner McGee.

[00:24:07] Kurtis Schaeffer: Music for this episode comes from Blue Dot Sessions. You can find

out more about our work at religionlab.virginia.edu or by following us on Twitter @thereligionlab. If

you're curious about Charlottesville's Confederate monuments, head to thesemonuments.org for a

recording of a tour offered by Dr. Andrea Douglas and our guest, Jalene Schmidt. If you like the

show, head over to iTunes or the platform of your choice to rate and review us. It really makes a

difference for new shapes like ours.

[00:24:44] Martien Halvorson-Taylor: This is our last episode of the season, but we'll be back this

fall with an episode that explores how Charlottesville is creating a new kind of public memory here

in Courthouse Square and across the city. Stay tuned.

There are hundreds of Confederate memorials across the United States. With our colleague Jalane Schmidt, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia, we explore an often-overlooked aspect of Confederate monuments: religion. Not only are these monuments typically steeped in religious symbolism, white Christian communities also helped to build and maintain them.

And we hear from a group of Christians here in Charlottesville wrestling with that legacy today.

How to cite this episode:

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K. (Presenters), Schmidt, J. (Guest), & Gadek, E. (Producer), “American Idols.” Sacred & Profane (2020, July 20).

Additional Reading

Douglas, Andrea, and Jalane Schmidt . Marked by These Monuments, WTJU 91.9 FM, www.thesemonuments.org/.

Natanson, Hannah. “Two women lead a free tour of Charlottesville’s Confederate monuments each month. A new website lets everyone listen.” Washington Post, August 20, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2019/08/20/two-women-lead-free-tour-charlottesvilles-confederate-monuments-each-month-new-website-lets-everyone-listen/.

Natanson, Hannah. “Are Confederate monument fans committing the sin of idol worship? An unusual Charlottesville Bible study makes the case.” Washington Post, September 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2019/09/13/are-confederate-monument-fans-committing-sin-idol-worship-an-unusual-charlottesville-bible-study-makes-case/.

Martin, Marcus L, et al. President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 2018, slavery.virginia.edu/.

Schmidt, Jalane. “What You Need to Know about Charlottesville’s Courthouse Confederate Soldier.” Medium.com, July 10, 2020, medium.com/@JalaneSchmidt/what-you-need-to-know-about-charlottesvilles-courthouse-confederate-soldier-f6f5e2cee5d4.

Schmidt, Jalane. “Humans Were Sold Here.” Medium.com, March 2, 2020. https://medium.com/@JalaneSchmidt/humans-were-sold-here-e326e28b03ad.

Additional Credits

Special thanks to voice actors Manfred Jones and Ben Richey.

(Top banner)

Photo: Ézé Amos. Plinth detail on the monument to Confederate General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, by Charles Keck, 1921, Charlottesville, Virginia.