[00:00:00] Kurtis Schaefer I'm Kurtis Schaefer.

[00:00:02] Martien Halvorson-Taylor and I'm Martine Halvorson Taylor. And this is Sacred and Profane, a show about how religion affects all sorts of decisions that we make in our daily lives.

[00:00:17] Kurtis Schaefer Today, we're highlighting documentary work done by students here at the University of Virginia in an ongoing series we call Field Notes, graduate student Kevin Rose studies how religion intersects with our fossil fuel based economy. In our first season, he helps us tell the story of a Hare Krishna community in West Virginia, which was faced with the decision to allow fracking on their land.

[00:00:45] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And now he's brought us this story of a Christian camp dedicated to seeking a more environmentally sustainable future but unable to extract itself from our unsustainable present.

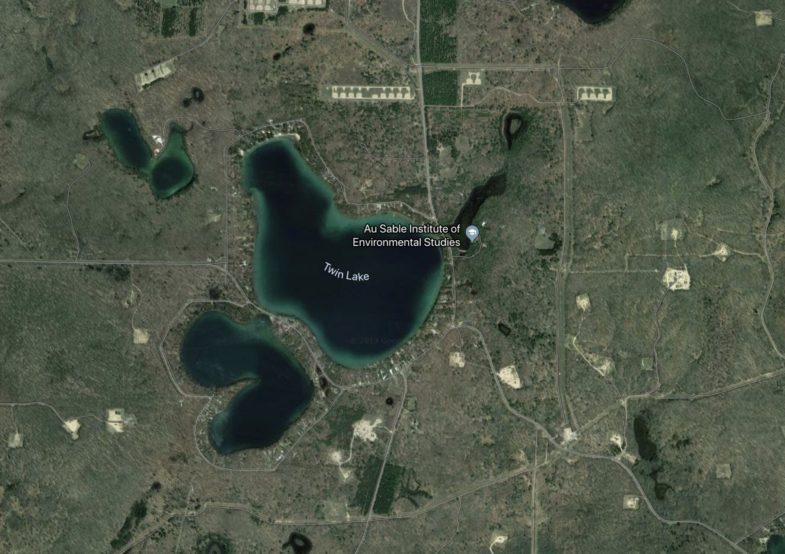

[00:01:08] Kevin Stewart Rose It's a typically busy weekday morning at the Au Sable Institute for Environmental Studies. We've got students from Christian colleges around the country are buzzing around this camp in northern Michigan packing mosquito nets and scientific instruments into big vans as they get ready for ecology classes out in the woods and wetlands around the camp.

[00:01:30] My name is Emily and this class is field techniques and wetlands. So that basically means because standing water.

[00:01:37] And we look at some trees and we look at some dirt. And we say, oh, yes, this is in fact, a wetland.

[00:01:46] Kevin Stewart Rose For Emily and the few dozen other college students taking summer classes with her ensemble offers a chance to complete some science credit hours while exploring the connection between their faith and the environment. The technical term for this kind of place would be a biological field station, but it's one that's set aside specifically for evangelical college kids.

[00:02:08] Emily I grew up trying to install recycling programs at my elementary school. It started at a very young age and it's always been very intricately tied into my Christian faith, which is really cool coming to our sabal and kind of getting my first glimpse of what a broader environmental Christian community looks like from the inside.

[00:02:28] Kevin Stewart Rose Au Sable looks like a pretty typical summer camp. There's a dining hall, a few cabins for campers and a large for evening social events. Everything surrounded by these dense, tall pines so that you can't always see the next building over, even if it's a stone's throw away. But over the last few decades, Au Sable has come to serve as something much more than a summer camp.

[00:02:51] Emily It's been amazing. You have so much in common with everybody. Just everybody's on the same page. And we're all super excited about the environment together.

[00:03:00] Kevin Stewart Rose You could call Au Sable a crown jewel for evangelical Christian ecology. Students from the major evangelical colleges around the country come here each summer to explore the link between their faith in the environment. What those students don't immediately know and what Ensemble's founders couldn't have predicted back when they started it was that there was something else bubbling beneath the surface that would link faith in the environment in a more complicated way.

[00:03:27] One of the most productive oil supplies in the region was right under their feet.

[00:03:37] When a high school science teacher named Harold Snider founded Osogbo Trails in the 1960s, he envisioned it as a summer camp where elementary school boys could explore the link between the Christian God and the woods around them. As one of Snyder's co-founders put it, all, Sabal at that time was focus less on full fledged Christian ecology and more on hikes in the woods. Singing hymns about God's creation.

[00:04:01] Bert Friesland My name is Bert Friesland. So when I met Harold Snyder, he was trying to start a Sabal Trails camp for youth, a camp for boys. Combine what was then called conservation and Christianity. And on the first few years, we just had boys from 10 to 13 and we had pretty much a typical camp program. And Harold, of course, taught the classes. You might call them nature classes. I got a letter from Amoco Oil Company one day because I was the treasurer and the business manager saying we would like to explore or do some seismic testing for oil under those 80 acres burned, ended up playing a key role with all the rights to do that.

[00:04:45] Kevin Stewart Rose Amoco's letter said it could offer a one eighth royalty, one eighth or one. Burt called up an acquaintance who worked for a much smaller still in Standard Peninsular Oil in Grand Rapids.

[00:04:54] He invited Peninsular to come do some drilling instead. And in the end, he negotiated a one fifth royalty with that local company.

[00:05:02] Bert Friesland As it turned out, it was probably one of the best oil wells ever hit in Michigan. And so he harvested, you might say, lots of money from that one 5th royalty. It was truly a godsend. And they just enabled us to take some real leadership in this Christian environmental movement.

[00:05:23] Bert, who takes a lot of personal pride and being responsible for that one fifth royalty, says he was receiving monthly checks for fifty thousand dollars in those first few years.

[00:05:35] Dave Mehan Certainly in those days, no one was talking about climate change.

[00:05:39] Kevin Stewart Rose This is Dave Mehan, one of the new staff that Au Sable was able to hire after it struck oil.

[00:05:46] Dave Mehan Everybody was just excited. It happened because Au Sable up to that point always never had enough money.

[00:05:51] I've always called it one of God's greatest ironies, that he gave a Christian environmental facility an oil well.

[00:05:58] Bert Friesland as a board, which suffered from a little bit of guilt because we seem to be engaged in an enterprise which is just contrary to what's going on in the world with respect to carbon footprints. And we've never come up with a clear cut answer as to how we can be related to the oil business in these times when there's so much concern about global warming. But we never really took any board action because we didn't know how to get out of it.

[00:06:26] But I don't think I can overstate the service we have done to God's kingdom.

[00:06:33] Kevin Stewart Rose With that money and with young people, for the young people who attend summer sessions here, those oil royalties have been crucial in creating their experience of Christian environmentalism. But as far as I could tell, none of the students I spoke with during that Wellins class even knew about the oil well yet.

[00:06:52] The camp directors do eventually explain their oil royalties to the students, but they do it at the very end of their summer session. After students like Emily have had their life changing experience and Christian environmental community mosquitoes are pretty active right here.

[00:07:10] Emily You see that? I can not.

[00:07:13] Heath Garris My calling is to glorify God through creation care. Currently at Au Sabal, I teach their field techniques in wetlands course.

[00:07:25] Kevin Stewart Rose That's Heath Garris, one of the professors at Au Sable, since the director of communications asked me not to bring the oil up with any students. I asked Heath to talk about how the students typically find out.

[00:07:37] Heath Garris So we have integration days. We all get together and do the same sorts of things in the field. And one of the integration days last year was sitting on an abandoned oil pad on the samples property and considering whether or not students would come to Isabell had they known beforehand that some of the reason why they're there and they're paying less money for it is because of the oil and gas industry. And we had students who sat there and said, oh, that's nice to know. And they you know, then it was time for lunch.

[00:08:07] We had a few students who were pretty emotional over this. They felt like they were coming to an environmentally conscious organization that was stewarding creation in the way that they had preconceived to be the best for the organization. And they felt like this was kind of a violation of that that they had expressed, wanting to have known that before they had applied and put deposits down and all that sort of thing. But that was kind of a minority position.

[00:08:34] We are always at risk of being called hypocrites by virtue of the fact that we drive fossil fuel driven vans, we eat food, we make waste. Being concerned for the environment is great, but claiming that you are having no impact on the environment is a bit hypocritical. But our job is not to live carbon zero.

[00:08:58] It's to make waves so that one day we might. And sometimes that involves burning fossil fuel.

[00:09:07] Kevin Stewart Rose This idea that whether it was right or wrong for Au Sable, to get involved in oil in the first place, they're stuck with the issue now, no matter what. That's something I heard from several people.

[00:09:18] Fred Van Dyke Now, the fact is that they're going to consume and emit a great deal of carbon based compounds in the work of protecting God's creation.

[00:09:30] Kevin Stewart Rose That's Fred Van Dyke, the current executive director of Au Sable. I asked Fred to take me out to see the well itself.

[00:09:37] Fred Van Dyke So I have to park and walk. OK.

[00:09:42] Kevin Stewart Rose But that won't stop even if Au Sable doesn't like the idea of depending on fossil fuels. Institute leadership like Fred say there's not a lot they can do about it. On the other hand, they still need to maintain its identity as this evangelical environmental organization. To do that, they've developed this carefully crafted and repeatable story about where the oil comes from.

[00:10:07] Fred Van Dyke The land that Harold Snyder originally bought was sold to him by a man named Louis Kleinschmidt.

[00:10:14] And the only reason we got a well is Harold had befriended a guy, Louis Kleinschmidt.

[00:10:19] Louie Louie was not well-liked in the county. He lived in a trailer in the woods. Harold befriended Louie because Harold, a genuine evangelical Christian, wanted to share Jesus Christ with Louis because he knew Louis, a local alcoholic.

[00:10:36] Bert Friesland Frankly, an alcoholic.

[00:10:38] Fred Van Dyke He needed to know Jesus Christ. Harold failed to bring him to a living faith in Jesus Christ. But he didn't fail to communicate to Louis that he loved Louie. Louie was not seen around for a while. A neighbor went to check on him at the trailer and found Louie inside dead. In the trailer, they also found that Louie had written a new will when Louie died.

[00:11:09] He gave that 80 acres to us.

[00:11:11] Bert Friesland He left us in his will.

[00:11:12] Eighty acres of land

[00:11:14] Fred Van Dyke he bequeathed to ASOL 80 acres of land.

[00:11:17] Bert Friesland And it was 80 acres of pretty much scrub land.

[00:11:20] Fred Van Dyke It was 80 acres of small, scrubby red pine. And Hole was discovered has been called by some the largest, most long lasting and most sustainable deposits of oil and natural gas in northern Michigan.

[00:11:37] Kevin Stewart Rose According to this story told again and again by the people at Au Sable, no matter what you might think about the fossil fuel economy in this country, that jack pump whirring away on their land was placed there thanks to its founders, Christian love.

[00:11:52] Bert Friesland We believe in the sovereignty of God. He put Harold Snyder here and me. He put Louis Kleinschmidt here. He put those 80 acres there. They brought the two of us together.

[00:12:04] Fred Van Dyke So this legacy that was given to the institute was a product and a direct effect of a disciple of Jesus Christ, loving somebody that nobody else loved.

[00:12:18] And eventually that person responded in the way that he could.

[00:12:26] Kevin Stewart Rose Even so, when they hear about it at the end of the summer, many of the students insist that the institution divest from the oil money the students displayed or poor ray of responses to that.

[00:12:39] Fred Van Dyke Some thought, yeah, it's time to shut the well down. Others said, no, we drove the vans here. The difference between us and maybe another field station is worth contributing to the supply for the demand that we are creating.

[00:12:57] Kevin Stewart Rose The truth is, landowners don't always have that much sway in the matter of oil extraction.

[00:13:03] That was certainly true for Au Sabal in 1975. At the time, thanks to something called the rule of capture, an oil company could legally take the oil from beneath you using a well across the street. In other words, if Au Sable had refused drilling on their land in the first place, that oil might have been extracted anyway. And according to Fred, divesting from the well now could mean seeing it transferred to new owners who would probably keep it pumping. And this is not just a Sobel's problem. It can be hard for all of us to see how to confront the entire fossil fuel system. And much easier to focus on personal behavior around things like consumption habits and solar panel projects. And that emphasis on personal choice meshes really well with evangelical faith, which is all about the Christian's personal relationship with God.

[00:13:56] Susan Walderman And so for me and learning about how the world works, it challenges me too. Well, how should I live in such a way that I'm a good tender and care of of creation?

[00:14:09] Kevin Stewart Rose That's Susan Walderman, a former student who now works with Fred on Ecology Research.

[00:14:14] Susan Walderman So I really take that to heart, my friends, when they come to my house, they always think it's so cold because I keep the thermostat low. You know, that's one small thing. I try to ride my bike as much as possible and think about how can I make one trip instead of four trips, you know, as those daily decisions and even the sorts of things that that we buy.

[00:14:34] Kevin Stewart Rose And some of these consumer choices can be really big, like Fred's goal of installing a field of solar panels near the oil well. And there's also some longer term activity going on. A bunch of research projects focused on restoration.

[00:14:52] Restoring prarie land and restoring the Baudin River with the dam removal. Restoring habitats in the kirtland's warbler and restoring forest on vacated oil pads

[00:15:07] Susan Walderman And we're approaching a vacated oil pad.

[00:15:10] And if we look over in that direction, you can see some Jack Pines that are starting to grow, distinguish them from the grass. And you can even see some of that red pines beyond the idea of trying to help restore whatever it is.

[00:15:29] In our case, a vacated oil pad is an important piece of it. And I think that that idea of restoration ecology fits well. And also, you know, it falls within that understanding that God is about restorative work. And so in doing research work related to that, it causes it or allows us to think.

[00:15:57] Kevin Stewart Rose These two strategies, daily consumer choices and the work of restoration.

[00:16:02] They help folks at Au Sable, deal with the irony of their dependance on fossil fuels.

[00:16:08] First, they reduce the connection between their personal choices and the issue of fossil fuel consumption. Then they step in to do restorative work in the fossil fuel industry's wake, an industry that has left the northern Michigan forest pockmarked with these rectangular wounds around the wells.

[00:16:27] This restorative work leaves that system intact, but helps Au Sabal process their sticky situation.

[00:16:34] Their dependance on the fossil fuel industry as beneficiaries of extraction. But in the short term, it's not always clear how much restoration is even possible in light of the deep impact the fossil fuel industry has on the land.

[00:16:50] Susan Walderman There was just the assumption that it would actually go back to forest land and it hasn't. This tree is number 17, you know, and it's only a few inches off the ground.

[00:17:03] We planted this tree five years ago. That's where the challenge is. Sometimes I have to remind myself when I when we can't find them, that I have a wonderful job outside, especially when the grass is really thick and you're looking for this thing that is only a few centimeters off the ground.

[00:17:32] So.

[00:17:36] Kevin Stewart Rose Back at the camp, the students, professors and staff still gather every week to sing praise songs and read Bible verses that affirm their religious commitment to caring for the Earth.

[00:17:49] In a week or two, Fred will take them to the oil well and tell them how all this gets funded. Some will feel like their rug's been pulled out from under them. This Christian environmental camp they've been at all summer is directly contributing to climate change. Maybe the biggest environmental issue we're facing, other students will think long and hard and decide it's worth it to pull that oil out of the ground. It means creating a place in the Michigan woods where they get to deepen their own care for creation. Like a lot of us, they feel stuck living in a world powered by oil.

[00:18:27] The structures around them can feel insurmountable. So they turned to the story that their faith tells them that they should focus on the choices right in front of them, what to do with the oil money and how to live in spite of their sticky situation.

[00:18:45] Singing It is well, in my soul

[00:19:04] Kurtis Schaefer Sacred and profane is produced by the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia. This piece was reported by Kevin Rose. Ashley Buffalo is our program manager. Our senior editor is Emily Garrick. Kelly Jones is the lab's editor.

[00:19:26] Kevin Stewart Rose Thanks to everyone at the Au Sable Institute for Environmental Studies, including former director Cal DeWitt and founder Garrett Crowe.

[00:19:33] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Music in this episode comes from Blue Dot Sessions. You can find out more about this episode and our work at Religion Lab DOT Virginia Dot Edu or follow us on Twitter at the religion lab. And if you like the show, please rate and review us on the platform of your choice. It really makes a difference to new shows like ours.

Nestled in the tall pines of Northern Michigan, the Au Sable Institute of Environmental Studies is a unique blend of Christian summer camp and biological field station. It’s an important institution in the world of evangelical environmentalism, or as the folks at Au Sable call it, “Creation Care.” But what students don’t always realize when they register for summer sessions there, however, is that all of this Creation Care is funded directly by oil royalties. In 1967, when a high school science teacher named Harold Snyder founded Au Sable Trails, a summer camp where elementary school boys would come to deepen their love for God and nature, he probably wouldn’t have predicted Au Sable’s future connection with oil either. But in 1975, amid an oil boom across the region, drillers hit perhaps the longest lasting and most productive oil well in Michigan right on Au Sable’s land.

That oil money that resulted funded Au Sable’s expansion into the environmental institute it is today. Each summer, dozens of students from Christian colleges around the country spend five-week sessions there, fulfilling science requirements through ecology courses in the lakes, forests, and bogs around the camp. At the same time, faculty and research associates engage in a number of ongoing ecology research projects they hope will help protect and restore the ecosystems of the region. And everyone at the camp gathers regularly for praise songs and prayers that celebrate God’s love for the environment.

It’s what former associate director David Mahan called “God’s great irony, that he gave an environmental institute an oil well,” and as others reflected to me, a situation that’s been really hard to unstick themselves from. I got interested in this story because I think, in a way, this is just a more intense version of the challenge many of us face: figuring out how to respond to climate change when our dependence on fossil fuels feels so darned unavoidable. There’s no consensus on this question at Au Sable. Some people are okay with what they see as a necessary compromise to fund all the work they do, although most look forward one day soon when the well runs dry and the institute no longer has to make it. Others are stunned when they hear about it, such as a few students who say they wish they’d known prior to putting down deposits on their summer session. In the end, though, I was most interested in how they use their faith to square with this sticky situation. Evangelical faith is deeply rooted in assumptions about free will and personal choice, just like many Americans’ faith in democracy is rooted in assumptions about their power to choose, despite the way the fossil fuel industry seems to have created so many entanglements with the government, with infrastructure, and with the economy that it can be hard to envision alternatives. So how do these assumptions about free will and personal choice get squared with a situation that feels so inevitable?

How to cite this episode:

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K (Presenters), Rose, K. (Reporter), & Gadek, E. (Producer). “Field Notes: Sticky Situation” Sacred & Profane (2020, June 1).

Additional Reading

Dochuk, Darren. Anointed with Oil: How Christianity and Crude Made Modern America. New York: Basic Books, 2019.

Fowler, Robert Booth. The Greening of Protestant Thought. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

LeMenager, Stephanie. Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Mitchell, Timothy. Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil. London: Verso Books, 2011.

Additional Credits

(Top banner)

Au Sable’s active well. Photo: Kevin Rose.