[00:00:00] Kurtis Schaeffer I'm Kurtis Schaeffer

[00:00:02] Martien Halvorson-Taylor I'm Martien Halverson-Taylor, and this is Sacred and Profane.

[00:00:07] Kurtis Schaeffer Our series about religion in unexpected places.

[00:00:09] Josué Buenas noches

[00:00:09] Jessica Marroquín This is Josué.

[00:00:09] Josué Hola...

[00:00:15] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And this is Jessie Marroquín. She's a PhD student here at UVA.

[00:00:23] Jessica Marroquín Hi, Martien.

[00:00:24] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Hi, Jessie.

[00:00:25] Jessica Marroquín Hi, Kurtis.

[00:00:26] Kurtis Schaeffer Hi, Jessie. Okay. We can't be distracted here. We have to get right back to Josué.

[00:00:31] Josué ¡Claro que sí!

[00:00:32] Jessica Marroquín Okay.

[00:00:33] Josué Gracias, gracias.

[00:00:38] Jessica Marroquín So Josué lives in Mexico. He wakes up early.

[00:00:42] Josué En lo mío, pues es levantarme temprano.

[00:00:44] Jessica Marroquín Does this chores.

[00:00:45] Josué Y empezar mis labores domésticas... (Josué laughs)

[00:00:45] Jessica Marroquín Takes his daughter to school.

[00:00:45] Josué Porque soy un padre de familia y tengo que..

[00:00:45] Jessica Marroquín And then goes to work for the family business.

[00:00:45] Josué Y me voy a trabajar.

[00:00:56] Jessica Marroquín On the weekends for fun, Josué rides his motorcycle with his MC, his motorcycle club.

[00:00:56] Josué (turns on his motorcycle). Mire, yo tengo tres motocicletas.

[00:00:56] Jessica Marroquín Before leaving the house, Josué prays to God and puts himself in his hands.

[00:01:14] Josué Me pongo en las manos de Dios que es el máximo creador.

[00:01:35] Jessica Marroquín Josué is a very devout man growing up, he says he even meant to be a priest.

[00:01:40] Josué Yo iba a ser sacerdote.

[00:01:42] Jessica Marroquín But it didn't work out.

[00:01:45] Josué Por circumstancias de la vida, ya no lo logré hacer.

[00:01:46] Jessica Marroquín In a country where 81 percent of adults identify as Catholic, it is not surprising that Josue so religious. What might be surprising is that he also has an altar in the corner of his room devoted to the saint of death.

[00:02:03] Josué Yo tengo un altar en casa, a mi Santa, a mi Santa Muerte.

[00:02:13] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So tell us who is Josué's Santa Muerte?

[00:02:17] Jessica Marroquín The short answer is she's a folk saint, meaning a saint who is embraced by believers but not recognized by the Catholic Church. If you've ever seen an image of her, she is very striking. Usually she's shown as a skeleton draped in long robes, sometimes dark, sometimes colorful. She wears a crown. Sometimes a simple crown of flowers. Sometimes something more royal with golden jewels. And like the Grim Reaper, she often carries a scythe. And that skeletal image is part of what makes Santa Muerte so controversial. Take Josué's family.

[00:02:56] Josué ... de una familia muy religiosa.

[00:02:58] Jessica Marroquín They're devoutly Catholic. And some were shocked when he started venerating the Santa Muerte.

[00:03:01] Josué Porque, como le vuelvo a repetir mi familia no estuvo muy de acuerdo.

[00:03:08] Jessica Marroquín They told him that she was evil.

[00:03:09] Josué Me decían que ella era mala, que por qué la tenía.

[00:03:22] Jessica Marroquín Josué's family also isn't alone in their distrust of the the. In 2016, Pope Francis visited Mexico City and met with Mexican bishops in the cathedral at the heart of the city.

[00:03:35] Pope Francis Me preocupan tantos...

[00:03:38] Jessica Marroquín He spoke about his worries that the drug trade is leading souls into temptation and demise.

[00:03:44] Pope Francis Que seducidos por la potencia vacía del mundo...

[00:03:47] Jessica Marroquín Although he never referenced the Santa by name, it was clear she was on his mind as he spoke of chimeras in macabre symbols connected to drug trafficking.

[00:03:58] Pope Francis ... exaltan las quimeras y se revisten de sus macabros símbolos que al final comercializan la muerte...

[00:04:11] Jessica Marroquín Symbols that commercialize and glamorised. And seduce followers away from true Catholicism. To Pope Francis, she embodies what is wrong in Mexico today.

[00:04:26] News reel 1 Y hablamos de México, ya que al menos nueve muertes es el saldo preliminar de la guerra urbana entre el demoninado cartel del noroeste y las fuerzas del orden.

[00:04:35] News reel 2 Last year was the deadliest year on record for Mexico's drug related violence has infiltrated all parts of society and all parts of the country.

[00:04:49] Jessica Marroquín Officially, two hundred and seventy five thousand people have been murdered in the last 24 years. And that doesn't count the tens of thousands of people who've disappeared.

[00:05:05] Jessica Marroquín It's not just Pope Francis who sees the Santa as a symbol that glorifies that violence. The Santa has been known as the patron saint of the drug trade, a kind of shorthand for violent death.

[00:05:21] News reel 3 These are pictures the detectives have taken from various crime scenes. A shrine to Santa Muerte complete with food and drink.

[00:05:29] News reel 4 Es bien sabido que la Santa Muerte ha sido venerada por criminales. Hecho que ha dañado la imagen del culto.

[00:05:43] Devotee of the Santa Muete Muchos lo tienen como algo malo. Nosotros no, nosotros lo tenemos como algo bueno.

[00:05:43] Kurtis Schaeffer And that's what we're going to talk about on the show today. Because despite the Santa's association with crime and violence as a kind of narco saint, her devotees have created one of the fastest growing religious movements in Mexico and the western United States, one that is not just compelling because of what's going on in Mexico today, but because of what her followers see as deep roots going all the way back to Aztec tradition.

[00:06:10] Jessica Marroquín And she is way more complicated and interesting than what you see on TV.

[00:06:22] Andrew Chesnut What she really is is the patroness the spiritual patronus of the narco wars in Mexico.

[00:06:30] Jessica Marroquín This is Dr. Andrew Chesnut.

[00:06:32] Andrew Chesnut I'm professor of religious studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. And what do I mean by that? Yeah, she has a robust following among cartel members, but also among Mexican law enforcement at all levels. At municipal, state, federal judiciales. I know I know for a fact that she is very popular also among law enforcement. It's both sides.

[00:06:58] Andrew Chesnut It's both sides.

[00:07:04] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Can you explain the distinction between being a narco saint and a saint of the drug war? That's a fascinating distinction.

[00:07:11] Jessica Marroquín So a lot of the news articles report on her being found on crime scenes. We start associating her with drug lords and the idea that killers are leaving her to sort of mark the scene of the crime. What Dr. Chesnut has studied is that she is really associated with anyone involved with the effects of the drug wars. And there are a lot of people whose lives have been touched by it, not even just law enforcement and traffickers.

[00:07:36] Kurtis Schaeffer So there's this sense that multiple kinds of people find meaning in her. It's not just people perpetuating violence, it's people who are victims of violence. People who are bystanders. I wonder if there's a sense that she helps people in times of uncertainty and that image of death provides a very realistic sense of certainty. We know we're all going to be there. And ironically, it provides some stability in the midst of a life that may seem profoundly unstable.

[00:08:13] Jessica Marroquín Absolutely. And I think that that is what we see in the veneration of the of the saint in Mexico, given the state of violence that the country has faced in the past 20 years. It is not surprising that people are turning to someone who is outside of the traditional church for protection. The church has not protected them. Catholicism has not been the answer for comfort or for certainty. In this case, people are turning to someone outside of the institution.

[00:08:45] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So she's sort of like a Saint Christopher. Is she viewed as protective?

[00:08:49] Jessica Marroquín Yes, definitely. You ask her for protection, but also for revenge, but also for good health. She's all of those things. She's very malleable. Whatever you need. You ask her to give you and provide.

[00:09:02] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Interesting.

[00:09:04] Kurtis Schaeffer So she's the antithesis of the Grim Reaper. She's not bringing death to you. She's using the power of death for you.

[00:09:11] Jessica Marroquín And I think that that's a really good point, Kurtis, that the Santa Muerte is... you're asking her or devotees are asking her for a good life. Right. That's all that they want. Whether that's through health or through protection, it's really not about death, even though her name is literally holy death.

[00:09:32] Kurtis Schaeffer In a Buddhist context in the Himalayas or on the Tibetan plateau, people people expect to see images of skeletons or even body parts in temples. And often they either represent deities or actually that have power. And if you make offerings to that power, they can bestow that protection upon you. If you don't, they can come and get you.

[00:10:02] Jessica Marroquín And that's a similar attitude to the Santa Muerte, you make her a promise you have, you should keep that promise.

[00:10:06] Martien Halvorson-Taylor You should keep that promise because she's awesome,

[00:10:10] Jessica Marroquín Because she is awesome and produces awe and miracles

[00:10:15] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And fear.

[00:10:22] Jessica Marroquín Also, something that is very important to know is Mexico is very much a place of huge diversity in cultures, right. We have such a a past that lingers very much in our present in terms of our indigenous diversity, those histories and those traditions and customs and beliefs that have fuzed with European Catholicism. So it's not just the violence. It's also that Mexico itself is already a place where it's very much open to mixed religions.

[00:11:00] Jessica Marroquín For her followers, that's a lot of her appeal. You can turn to her for anything for help with love, wealth, protection.

[00:11:09] Jessica Marroquín She also represents a link to Mexico's pre-hispanic past.

[00:11:15] Josué Cómo explicarle...

[00:11:24] Jessica Marroquín Josué explains that she is an angel of God.

[00:11:35] Josué Ahorita es conocido como el arcaangel, como el arcángel Azrael.

[00:11:41] Jessica Marroquín But also an embodiment of the Aztec or Mexica dieties of death, Mictlantecuhtl and Mictecacihuatl.

[00:11:53] Josué Nosotros veníamos con Mictlantecuhtli y después fue Santa Muerte.

[00:12:02] Jessica Marroquín Josué says that after the conquista, the Catholic Church spoke ill of these gods and banned their worship.

[00:12:02] Josué Sí, entonces, hay muchísima, muchísima gente fue asesinada por creer en Mictlantecuhtli.

[00:12:02] Jessica Marroquín In this way, he believes how the Church approaches the Santa Muerte now is really similar to how the Church tried to suppress indigenous religion centuries ago,

[00:12:13] Josué La iglesia, la Iglesia fue la empezó a hablar mal de ella... empezó que, pues puso en mal a la Santa Muere.

[00:12:29] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So so what's what's the appeal to people now to make that link?

[00:12:33] Jessica Marroquín Well, I think that we talk about the pre-hispanic duties or culture as something that is exactly that, "pre-hispanic," but it's actually something that is very much in our present in Mexico today. And I think that how you create the identity of Mexico is very much tied to the pre-hispanic cultures. The Santa Muerte for devotees could be a mix of Catholicism and indigenous practices. It's a way to maintain that identity of Mexico as this melting pot that is fully inextricable from this past. So it's not a past. It's a present.

[00:13:12] Kurtis Schaeffer What kinds of evidence do people point to when they connect Santa Muerte with the Mexican past?

[00:13:20] Jessica Marroquín Right. That's funny that you say Mexican pass because devotees in Mexico City are literally connecting her to them Mexica or what we call the Aztec past. So I have that same question. And I spoke to an archaeologist in Mexico City who took me to archeological sites to show me some artifacts and see if there's a connection between that past and the Santa Muerte.

[00:13:44] Kurtis Schaeffer So what did you do with the archeologist?

[00:13:47] Jessica Marroquín Yes, so Lorena Vasquez is an archaeologist that I met at the Templo Mayor museum that has amazing artifacts. And if you haven't been, you should absolutely go.

[00:14:00] Jessica Marroquín And she walked me to this side street right next to the Zócalo. So you see all these people, hear all these noises. And she moved this piece of wood, just this plank off of this historic building. And we go up the second story. And this place used to be an apartment building. And they discovered an enormous tzompantli.

[00:14:38] Lorena Vázquez Sí, entonces buscábamos los indicadores arqueológicos para poder decir que aquí había un tzompantli, no?

[00:14:39] Jessica Marroquín An Aztec skull rack. This particular tzompantli has about a thousand skulls.

[00:14:44] Lorena Vázquez Mil craneo, más o menos.

[00:14:46] Kurtis Schaeffer And tell us what a skull rack is.

[00:14:48] Jessica Marroquín Yes. So the skull rack is where the assets used to display publicly skulls of children, women, and adults...

[00:14:58] Lorena Vázquez Hay muchísimos que no se ven.

[00:14:59] Jessica Marroquín We still don't know exactly why we go based off of the descriptions of the Conquistadors, or the Spaniards, who arrived and described there awe.

[00:15:11] Lorena Vázquez Leyendo a los conquistadores, a los cronistas.

[00:15:15] Jessica Marroquín But our interpretation is that the tzompantli was part of the religious sacrifices to the dieties of death. Visually, it's easy to see a connection between the Aztec tzompantli and the Santa Muerte.

[00:15:28] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Right. So you have these these powerful divine beings closely associated with skulls and skeletons and with death.

[00:15:37] Jessica Marroquín Right. But academics debate whether or not there is an unbroken link from the Aztec cult of death to the Santa Muerte today.

[00:15:54] Lorena Vázquez Yo veo que son dos cosas diferentes porque además es una deidad que es distinta a estas deidades.

[00:16:01] Jessica Marroquín You could say this sort of personification of death is an idea that came about in two separate belief systems. In fact, the Santa's long black robes and scythe also point to roots in la parca, medieval Spain's version of the Grim Reaper, who's also female.

[00:16:11] Kurtis Schaeffer So you talked about this idea of death in two different traditions. We can see the connection visually between Aztec tradition and the Santa. Even if we don't fully understand the ritual behind things like tzompantli. So can I ask, is there any historical evidence that she has related to La Parca beyond the robe inside?

[00:16:29] Jessica Marroquín There is evidence in the sense that there are religious texts that have drawings or illustrations of skulls and skeletons that accompany sermons or moralizing texts.

[00:16:44] Kurtis Schaeffer Santa Muerte is the Grim Reaper. Right?

[00:16:47] Jessica Marroquín I think that that's too simple to say.

[00:16:49] Kurtis Schaeffer OK. Yes. So tell us about that sameness and difference.

[00:16:53] Jessica Marroquín I think the difference is the Grim Reaper is not venerated as a god or goddess. The Grim Reaper is coming to get you when your time comes. You better be good because your time will come and you're either going to have to suffer the consequences after you die or you're going to welcome it since you've let it good moralizing life. You followed the code, but the Santa Muerte has no code to follow their promises. The devotees make her a promise. She protects them. So there's very... even though esthetically looks similar. I think that that's why it's so confusing. Right? Just because you have skulls and skeletons doesn't necessarily mean they're one and the same. It means that maybe they're connected in some ways but they gain different meaning depending on the time and context.

[00:17:33] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Ok, but despiot this, it seems like people, or followers like Josué are interested in making a connection between historical Aztec deities and the Santa Muerte.

[00:17:46] Jessica Marroquín Right. And I think that that is both because that is such a relevant past in the present, but also it legitimizes the Santa Muerte, right? If she's connected to these ancient old traditions, beliefs, customs, then the send them where there is technically older than the Catholic Church. Right? Or has been present for such a long time that their veneration is valid or legitimate.

[00:18:25] Kurtis Schaeffer The Santa's primary strength seems to be that she can embody so many contradictory traditions and values.

[00:18:32] Jessica Marroquín Absolutely. Andrew Chesnut would definitely agree with you.

[00:18:37] Andrew Chesnut She is malleable. I mean, there's no doubt that she is the result of religious syncretism. The Spanish bring La Parca that these indigenous groups view through their own religious lens. And so turn the Spanish grim repressed into this miraculous, miracle working, supernatural figure that she is today.

[00:19:06] Jessica Marroquín Whether or not she has unbroken roots to the Aztec past believers are mixing a lot of traditions indigenous, Catholic and even secular into one avatar.. For example, it is now common to see a rosary service for the Santa on the 1st of every month at some public sanctuaries, places of gathering or chapels.

[00:19:26] Andrew Chesnut We all know that the rosary is the epic prayer dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the Santa Muerte rosary is basically the same, just substituting out some of the lines, dedicating it to Santa Muerte instead of the Virgin.

[00:19:43] Jessica Marroquín In the past, people used to venerate the send them where that behind closed doors today walking around Mexico City. You can see her on street corners. There are murals, altars, and shrines devoted to her. And she's also on people's bodies, on tattoos, clothing and jewelry, and phone cases. She's become a part of everyday life.

[00:20:11] Josué ¿Quiere que le prenda mi moto?

[00:20:20] Jessica Marroquín That's the bike that Josué rides as a member of the Santa Muerte Motorcycle Club. He says every time he rides, she rides with him.

[00:20:31] Josué Como favor, se lo pido a mi Santa, a mi Santa Muerte.

[00:20:47] Jessica Marroquín Literally, on his jacket, watching and protecting. Josué was a rider before he was a believer. One day he was riding with his old motorcycle club and he saw a group of 200 riders arrive in a parking lot. They all had black leather jackets on with a female skeleton figure on their backs. It was the Santa Muerte motorcycle club. Josué admits he was afraid of them.

[00:21:09] Josué Me daba miedo. En primera, porque era algo que yo no conoció. En segunda, por lo que le comento, que aquí es conocida la Santa Muerte para gente mala.

[00:21:25] Jessica Marroquín I tell them it must be wild. Now that he's one of them, to see people's reactions when a large group rides up in jackets with skeletons on their backs.

[00:21:34] Josué (laughs)

[00:21:36] Jessica Marroquín Josué laughs and admits that like he did at first, some roll up their windows or walk away. But he says people mostly ask him if they can give the Santa cigarettes.

[00:21:48] Josué Ofrezco cigarros, veladoras, tequila, cerveza, a la Santa que es lo que, como ofrenda.

[00:22:02] Jessica Marroquín They want to make offerings to her. Say hi to her. Even take selfies with her.

[00:22:11] Jessica Marroquín Despite what the historical evidence may say, the pope may say or what family members may say. There are devotees from all walks of life who are turning to her, have faith in her and believe in her.

[00:22:26] Jessica Marroquín Josué is obviously one of them, and his faith has not dimmed after nine years of writing with the sentence where the motorcycle club. He is currently waiting impatiently for the club's next vote.

[00:22:40] Jessica Marroquín If approved, he will tattoo the Santa on his body and carry her with him wherever he goes.

[00:22:49] Josué En este caso, la Santa Muerte es una intercesora, es una intercesora como otros seres divinos.

[00:23:20] Kurtis Schaeffer Sacred and Profane was produced for the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia. Jessica Marroquín reported this episode for us. Our senior producer is Emily Gadek. Our program manager is actually Ashley Duffalo. Kelly Jones is the Lab's editor.

[00:23:37] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Music for this episode comes from Blue Dot Sessions. You can find out more about our work at religionlab.virginia.edu or by following us on Twitter @thereligionlab. You'll also see pictures of the Santa from Jesse's original reporting. And if you like the show, please head over to iTunes or the platform of your choice to write and review us. It really makes a difference for new shows like ours.

Santa Muerte. Holy Death. To outsiders, she’s become a symbol of cartel driven violence in Mexico—a “narco-saint,” worshiped only by traffickers, and venerated at crime scenes. To her followers, she’s a protector with roots stretching back to the pre-Hispanic past.

Dr. Jessie Marroquín joins us to explore the complex history of the saint, now one of the the fastest growing religious movements in Mexico and the Southwestern U.S.

Aesthetics Embodied: The Emergence of la Santa Muerte in the Catholic Democratic Public

By Jessie Marroquín

Since the early 2000s, we have seen a proliferation of studies on a genealogy and understandings of the folk saint, la Santa Muerte (Holy or Saint Death) in Mexico. Scholars have focused on either establishing or disproving connections between the pre-Hispanic adoration of la Santa Muerte and the development of the modern Mexican nation-state (c. 1920s-2000s). Since the drug war began in 2006, and violence increased, la Santa has been imagined as a narcosaint. My project adds to this existing body of work.

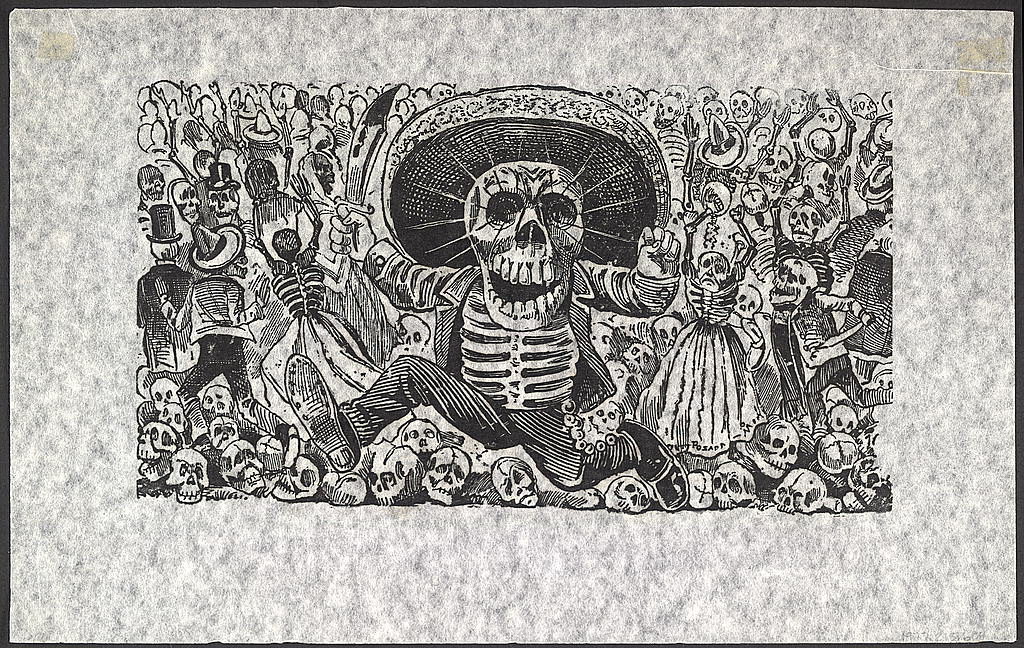

Scholars posit that modern worship of la Santa Muerte is a mixture of medieval European and Amerindian indigenous practices and aesthetics—with inherited elements of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Mexicas, the colonial Catholic danse macabre, and the now-famous Day of the Dead imagery produced by José Guadalupe Posada (c. 1910-1913). Posada’s engravings were published at the onset of the Mexican Revolution, the only other period in Mexico’s history characterized by a level of violence which rivals that of today. I am interested in the nuances of this “jump” from Posada’s political engravings all the way to a type of public rebirth of la Santa Muerte in a democratic society permeated with daily violence.

In 1910 this fierce calavera appeared in a broadside with the headline “Calaveras del montón, número 1,” reproduced in Posada’s Mexico / Ron Tyler. Washington, D.C. : Library of Congress, 1979, p. 268. Part of: Caroline and Erwin Swann collection of caricature and cartoon (Library of Congress).

I am interested in questions such as, what is the relationship between a fragmented body politic, drug violence, and the emergence of a privately worshipped figure in public spaces? What does this story tell us about class, race, and ethnicity in Mexico’s violent, corrupt democracy? Can we rethink la Santa Muerte as not only a narcosaint, but also as a historic, rebellious figure to the institutionalized Catholic democracy in Mexico? Is she a continuation of Catholicism or marks a rupture with Catholicism?

As part of my research for this podcast, I had the opportunity to travel to Washington D.C. to work with the Posada collection at the Library of Congress. I also travelled to Mexico City where I visited museums such as the Templo Mayor and the Museo de Antropología, walked and explored the streets of the busy city, spoke to devotees of the Santa Muerte, and met with scholars who helped bring this project to light.

If you would like to learn more about the Santa Muerte, you can visit websites, such as https://skeletonsaint.com/, or look at the resources listed below. These are just a selection of some studies among many that have and continue to be published.

How to cite this episode:

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K. (Presenters), Marroquin, J. (Reporter), & Gadek, E. (Producer), “La Santa.” Sacred & Profane (2020, May 4).

Additional Reading

Adeath, Claudia and Regnar Kristensen. La Muerte De Tu Lado. Fundación del Centrohistórico de la Ciudad de México. Libros de la Meseta. 2007.

Brook, John L. Blood + Death: The Secret History of Santa Muerte and the Mexican Drug Cartels. Headpress. 2016.

Casal Sáenz, Heber. La Santa Muerte: el culto de los que oran y los que matan. L.D. Books. 2016.

Chesnut, Andrew R. Devoted to Death. Oxford University Press. 2012; 2018.

Flores, Juan Antonio. “La Santísima Muerte en Veracruz, México: vidas descarnadas y prácticas encarnadas”, in Juan Antonio Flores and Luisa Abad González (eds.), Etnografías de la muerte y culturas en América Latina. Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. 2007.

Fragoso, Perla. “De la calavera domada a la subversión santificada. La Santa Muerte, un nuevo imaginario religioso en México.” Cotidiano, vol. 26, no. 196, 2011, pp. 5–16.

Kristensen, Regnar. “La Santa Muerte in Mexico City: The Cult and its Ambiguities.” Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 47, no. 3, 2015, pp. 543-566.

Lomnitz, Claudio. Death and the Idea of Mexico. Zone Book. New York. 2005.

Mobio, Francis. Santa Muerte: Mexico, La Mort Et Ses Dévôts. Imago. 2010.

Perdigón Castañeda, Katia. La Santa Muerte, Protectora de los hombres. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. 2008.

Reyes Ruiz, Claudia, and Editorial Porrúa. La Santa Muerte: historia, realidad y mito de la niña blanca: retratos urbanos de la fe. Editorial Porrúa. 2010.

Uriarte, Raúl R. and José Luis Cisneros. “De la niña blanca y la flaquita, a la Santa Muerte: hacía la inversión del mundo religioso.” Cotidiano, 26: 169, 2011, pp. 29–38.

Additional Credits

I personally want to thank the Religion, Race & Democracy Lab for making this project possible. I am also in debt to professor Dr. Andrew Chesnut (Virginia Commonwealth University), anthropologist Dr. Roberto García Zavala Roberto (Universidad la Salle Mexico), archaeologist Lorena Vázquez Vallín (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), photographer José Luis Guadalupe, and other collaborators who have chosen to remain anonymous. This podcast would not have been possible without their participation and collaboration.

(Top banner)

Close-up view of Santa Muerte south of Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. Photo by Not home. Transferred from en.wikipedia, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3538006