[00:00:05] Orly Minazad There were no plans to leave.

[00:00:09] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Orly Minazad was born in Iran after the Islamic revolution swept the Shah from power.

[00:00:16] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Almost overnight it seemed the country had changed.

[00:00:21] Orly Minazad My dad thought things were going to get better. But you know the revolution ended and then it was that Iraq Iran war. You just didn't know when you were allowed to leave. It was just... you were packed and you were just waiting.

[00:00:36] Orly Minazad One day I was at school and they called me to the principal's office and my mom came in and said we're leaving.

[00:00:42] Orly Minazad So I came home. I said goodbye to my nanny and my grandmother and we just left. And that was it.

[00:00:55] Martien Halvorson-Taylor By the time Orly was 8 she and her family were living in Los Angeles home to the largest Iranian community outside Iran and the home of many Iranian Jews including Orly's family.

[00:01:09] Orly Minazad And I've been here ever since

[00:01:12] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Before we hear the rest of Orly's story, let's introduce ourselves. I'm Martien Halvorson-Taylor.

[00:01:17] Kurtis Schaeffer And I'm Kurtis Schaeffer. Martien and I are both professors here at the University of Virginia.

[00:01:22] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And this is Sacred & Profane, our series exploring how religion shapes the world around us and how we shape religions.

[00:01:31] Kurtis Schaeffer Orly grew up along with her brothers and sisters in L.A. these days. She's a freelance writer and a lot of what she writes about is the city's thriving Iranian American community. Which is how she found herself looking at an ancient piece of clay that came to L.A. as Getty Museum, back in 2013.

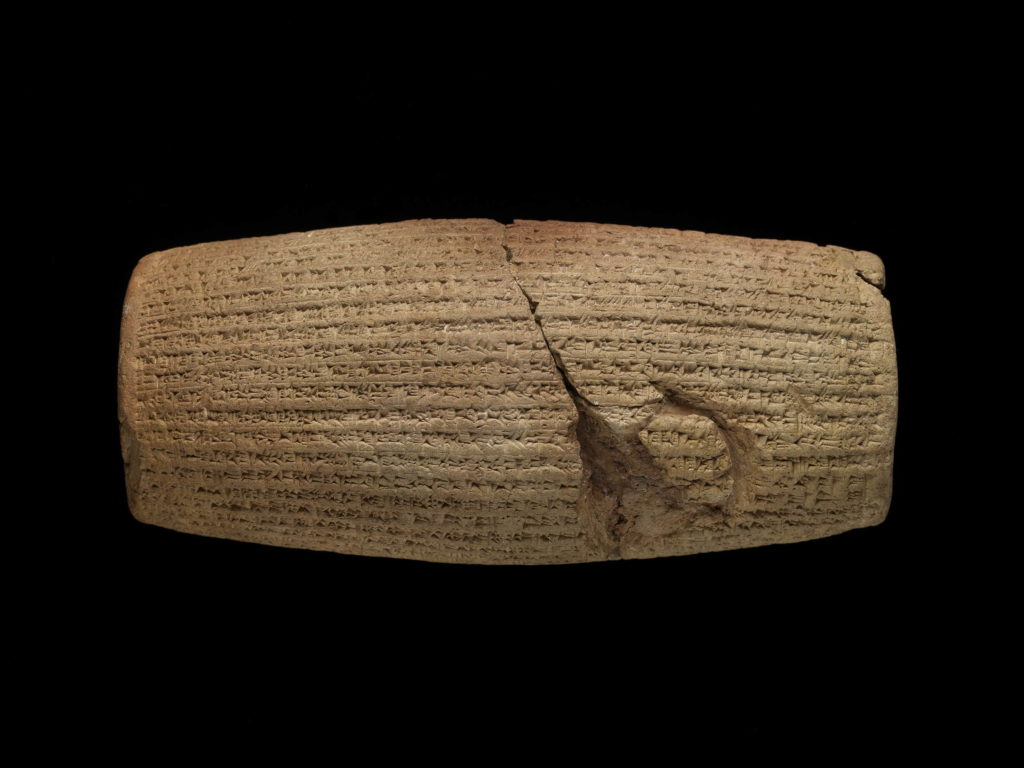

[00:01:55] Orly Minazad You know it's funny the way they presented with the lighting in this glass case is very, very melodramatic. I mean the actual artifact is not it's not a beautiful piece of art. It's just art because of what it stands for because of the context of it.

[00:02:13] Martien Halvorson-Taylor If you didn't know what this lump of clay was this artifact it's not very impressive visually. Orly calls it the Keith Richards of the ancient world. Like him, it's somewhat ravaged by time, but still vital.

[00:02:31] Orly Minazad I think what was more interesting for me was other people watching it and looking at it and explaining to their children me explaining it to my nieces and nephews.

[00:02:41] Martien Halvorson-Taylor People are drawn to this particular object not because of what it looked like but because of who wrote it and what it symbolizes. It's written in the name of Cyrus the Great a conqueror whose ancient empire began in what is now Iran and spread across the Middle East.

[00:03:00] Kurtis Schaeffer You could look at this clay cylinder. This cuneiform Keith Richards as the other side of one of the most well-known stories of the Hebrew Bible.

[00:03:09] Martien Halvorson-Taylor This cylinder, written in Akkadian, is an edict issued after Cyrus captured Babylon. It allowed conquered peoples who had been brought to the city over many years to return home. In the Bible Cyrus's edict is seen as a chance for the Jews to return to their homeland and to rebuild their temple. After decades of exile and Babylon. And, as the Bible tells it, that's not random good luck. It's God working through Cyrus. You can hear this in the prophet Isaiah's description of Cyrus and his victory.

[00:03:51] Reader Thus says the Lord to his anointed to Cyrus whose right hand I have grasped to subdue nations before him and strip kings of their robes. I have aroused Cyrus in righteousness and I will make all his paths straight. He shall build my city and set my exiles free.

[00:04:14] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Many like Isaiah have seen Cyrus his edict as a divine command and as an invitation to return to their homelands. But that's not the only interpretation.

[00:04:28] For some it's been a sign of religious tolerance — a ruler giving his people permission to freely worship their own gods, in their own lands. It's even been called the first declaration of human rights.

[00:04:43] Clip Cyrus, King of kings. Champion long before Magna Carta of human rights liberties

[00:04:52] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And it has a long history of popping up in politics around the world.

[00:04:58] Clip I want to tell you that. We remember the proclamation of Cyrus the Great. Great king, Cyrus the Great. Persian King. And we remember how a few weeks ago President Donald J Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital

[00:05:17] Martien Halvorson-Taylor For Orly, Cyrus's edict is proof of Iran's long history of religious tolerance and diversity a tradition that laid the cornerstone for modern democracies like the United States.

[00:05:32] Orly Minazad I think immigrants are just constantly trying to justify their existence in a new country. For Iranians in LA, it's come to mean that here is two thousand five hundred years ago we we Iranians had a ruler who was way more tolerant than most rulers are not even in our own country. You know even in our own American political climate and this was a confirmation that you know we can also belong.

[00:05:59] Orly Minazad I mean it still has lessons to teach.

[00:06:03] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Today on the show we'll explore some of the many ways people have interpreted Cyrus's decision to send conquered peoples home. As divine intervention. As pragmatic propaganda. As a symbol of human rights and religious freedom.

[00:06:20] Kurtis Schaeffer We'll try to understand why he may have been motivated to write the decree in the first place and more importantly we'll think about why and how his decree has remained meaningful to us millennia later. Why has the decree of an ancient monarch been held up as an example of modern democratic ideals? And how much do Cyrus's original intentions matter?

[00:06:32] Kurtis Schaeffer But before we can appreciate what Cyrus's decree might mean to us today, we have to at least try to understand what Cyrus intended 2500 years ago.

[00:06:43] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Let's go back to the account of Cyrus his edict that's best known today. The Hebrew Bible Cyrus actually appears in the Bible multiple times. This is from the Book of Ezra.

[00:06:59] Reader The Lords stirred up the spirit of King Cyrus of Persia so that he sent a Herald throughout all his kingdom and also in a written edict declared. Lord the God of Heaven has given me all the kingdoms of the earth and the has charged me to build him a house that Jerusalem in Judah. Any of those among you who are of his people are now permitted to go up to Jerusalem and Judea and rebuild the house of the Lord the God of Israel.

[00:07:31] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Ezra reflects how some Jewish authors understood Cyrus like the prophet Isaiah. Ezra I believe that even though Cyrus was a foreigner and worship different gods he was still an instrument of their god an instrument who delivered God's chosen people back to the homeland.

[00:07:51] Martien Halvorson-Taylor But the text doesn't tell us much about who Cyrus was or what his own intentions may have been.

[00:07:58] Mark Hamilton Well what do we know about him in general that he was. He was a king of a small region in what's now western Iran.

[00:08:07] Martien Halvorson-Taylor That's biblical scholar Mark Hamilton.

[00:08:10] Kristin Swenson He did grow an empire to be the largest the world had ever seen and that extended from what is modern Greece all the way over to what is modern India and South to the oceans and the seas.

[00:08:28] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And this is biblical scholar Kristin Swenson. Mark and Christian both studied the ancient near east and they'll be helping us to tell the story today. As Kristin said By the time Cyrus died his empire was the largest that had ever existed at the time. But despite that there's lots we don't know about Cyrus his life. We don't know very much about his parents or his early life or what his own religious beliefs may have been. He's a bit of a mystery in many ways.

[00:09:01] Mark Hamilton What we do know is that his actions broke with policies of empires have gone before him and we know that he conquered Babylon and 539 B.C. while he would go on to conquer much of the modern Middle East.

[00:09:25] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Babylon was in many ways the centrepiece of Cyrus his empire. It's located in modern day Iraq so geographically it was right at the heart of things. And it was a prize one of the oldest largest and richest cities in the world. Long before Cyrus came to town. Babylon had become powerful and wealthy by conquering its neighbors particularly under an earlier king named Nebuchadnezzar.

[00:09:56] Kristin Swenson Nebuchadnezzar was a very successful conquer when he defeated a peoples and he did that all over the known world. He took their best and brightest with him back to Babylon and put them to work for Babylonia.

[00:10:19] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Those conquered peoples brought there against their will help to build the palaces temples and gardens that made Babylon a wonder of the world. But by the time Cyrus arrived there was tension building in the city as, well. In part because of all these conquered foreign people, including the Jews, that Nebuchadnezzar had brought in.

[00:10:43] Kristin Swenson So it was a really cosmopolitan court. But you can imagine that not all the Babylonians were thrilled with seeing foreigners assume positions that were well-respected. As these artisans as scribes as judges I mean there were some very high positions occupied by people who had come from defeated countries

[00:11:09] Martien Halvorson-Taylor And that all of this was making Babylon...less Babylonian.

[00:12:04] Kristin Swenson So it seems that in the Babylonia of that moment before Cyrus conquers the empire the population itself was divided. Different people have different ideas about how their country should go forward. There were those who were amenable to foreigners that there were some people who felt very strongly that Babylonia should be composed of blood Babylonians people who were born and bred there.

[00:12:47] Kurtis Schaeffer So you could say Cyrus is really facing quite a dilemma. On the one hand he's gaining control of this incredibly wealthy sophisticated city on the other hand it seems that the city is ready to fracture into pieces. So what does he do. What's his move.

[00:13:05] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Well not long after he enters the city, he creates that cylinder shaped artifact that we've been talking about. The one that Orly saw in L.A. Inscribed on it is his edict written in the language that would have been spoken by native Babylonians at the time. And you could hear Cyrus's words as a kind of promise of a new day for a divided Babylon.

[00:13:30] Reader I am Cyrus, king of the world, great king, mighty king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters. When I entered Babylon, I took up my lordly abode in the royal palace, amidst rejoicing and happiness. My vast army marched into Babylon in peace. Marduk, the great Lord, rejoiced over my good deeds. By his exalted word, all the kings who sit upon thrones throughout the world, from the Upper Sea to the Lower Sea, brought their heavy tribute before me, and in Babylon they kissed my feet.

[00:13:57] Mark Hamilton He says that his his actions are motivated by the gods.

[00:14:03] Kristin Swenson He calls it kind of liberating them.

[00:14:07] Reader (CYRUS) I sent [the gods] back to their palaces to the cities of Ashur and Susa, Akkad, the land of a Eshnuna, the city of Zambon, the city of Marturu, Der, as far as the border of the land of Qutu, whose shrines have become dilapidated. I made permanent sanctuaries for them. I collected together all of their people and returned them to their settlements. I returned the cards unharmed into sanctuaries that made them happy. Make all the gods I returned to their sanctuaries ask a long life for me, and mentioned my good deeds.

[00:14:48] Kurtis Schaeffer I see a few differences from the story in the Bible. For one Cyrus is really focusing on Babylon and the chief god Marduk. But at the same time there are things that have the same sort of ring to it. Cyrus is claiming divine inspiration saying that he's doing what Marduk and these other gods want and he is sending both gods and people back to their homelands. I can definitely see how you can read this as a text of religious tolerance or perhaps cultural tolerance. Cyrus is saying hey go put your gods back in their home temples. Do what makes your gods happy. And it's not just the state turning a blind eye to these other religions. Cyrus is promising to actively support them all and to rebuild their temples.

[00:15:31] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Yeah exactly. And and the fact that we do have these similar but very different stories is interesting. It shows how various people very early on made it their own. And the Cyrus Cylinder very well may have been motivated by a certain religious tolerance toward conquered peoples and perhaps even to their gods. But I think we can also look at this as a savvy political decision.

[00:15:56] Kristin Swenson He allowed so to speak a number of foreigners to return to their native lands who had been conquered by Nebuchadnezzar. Now that makes you popular in a couple of ways. One among the foreigners who might want to go back but the other is among the native Babylonians who would have been happy to see good riddance to those people who came wandering in that weren't from here originally.

[00:16:23] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So let's look at this from another angle. There's also the question did conquered peoples in Babylon actually want to go home. The accounts of Cyrus's decree and the Bible make it sound like joyous liberation but we know that some of the Jews had been in Babylon for decades and we know from written records that many had flourished there. They wrote contracts they own businesses they gave their children Babylonian names they had put roots down in the city with this decree have felt like an invitation to go home or an edict of expulsion.

[00:17:03] Kristin Swenson I think it would have felt like that to a lot of people. And remember we're talking about 40 years here a generation between the conquest and their return. And so a lot of people who were urged to return to their native land actually may have felt more Babylonian than anything. We read that Cyrus provided all this support, which sounds so nice. But he may have been bribing them also to get go back. I promise you I'll give you some stuff and help you get your feet on the ground. But please...do go.

[00:17:44] Martien Halvorson-Taylor This came up when I was speaking with Orly about her own family.

[00:17:48] Martien Halvorson-Taylor As someone who's been living here for a long time. If there were a similar decree the U.S. and Iran worked out a way that you could go home. Would you take it.

[00:18:01] Orly Minazad I think I would visit. My mom and my aunts and uncles would just run the first flight back. You know I don't think they ever got used to living here. So for me it would be a little bit more difficult. You know I've been here since I was eight years old. My life is here. It would be very difficult for me.

[00:18:22] Kurtis Schaeffer Whatever your conclusions about Cyrus's motivations the edict shows how people and their governments have been wrestling with the same question for thousands of years. At what point is a commands to return home. A liberation. And at what point is it another form of exile who is an insider who is an outsider.

[00:18:41] Mark Hamilton We know human migration is a phenomenon that goes back as far as we know anything about human beings that goes back as long as we have text. I think it must go back well before writing. People think about how how we're going to live together. We can't read their minds.

[00:19:09] Mark Hamilton All we can do is read their text. And if you read the Cyrus Cylinder, one thing the cylinder and the text like it might say to us is the state does have a responsibility to think about the well-being of human beings that it comes into contact with and that should be its first priority.

[00:20:02] Kurtis Schaeffer So we've got this ancient edict. Whose original intention is kind of a mystery and a lot of ways. We've got people like Orly Minazad in Los Angeles who see it as a real symbol of the best of their culture and the best of human impulses. How should we look at it?

[00:20:18] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Yeah I'm I'm wrestling with that too. And so I decided to go look at the object itself... or more accurately a replica of the original that the Shah of Iran gifted to the United Nations, back in the 1970s.

[00:20:33] Guide Do you know where the Cypress Cylinder is?

[00:20:33] Martien Halvorson-Taylor The Cyrus, the Cyrus Cylinder.

[00:20:37] Guide I'm not sure. OK.

[00:20:39] Martien Halvorson-Taylor It's tucked a bit out of the way. But eventually we found it. Near the Security Council chambers.

[00:20:47] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Oh my gosh. There it is. It's so tiny. It's like it's like a football. That's amazing. I am Cyrus king of the world great King, mighty king.

[00:21:03] Kurtis Schaeffer So what did you feel like looking at it. Did it change anything for you.

[00:21:06] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So, Kurtis visually just seeing it was like this reminder from ages past of how we've been trying to work out the relationship between nations and dispossessed people for centuries. Right. It's it's an artifact of that long standing struggle and the fact that it's at the U.N. which deals with those issues every day was a sort of a potent reminder of how we haven't figured this out. The other thing I was really struck by is the bombast of the translation and it and it maybe even mistranslates the cylinder to make it a more sweeping edict than it actually was. Because it was appealing as you say to our better impulses we should all be free we should all be liberated we should all be able to go home.

[00:21:58] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So translations matter a lot hinges on them and they should be carefully done. Otherwise we're rewriting history or misreading history. On the other hand this translation if it is a mistranslation is aspirational in ways that that are probably very important for people you know racing by it at the U.N. if they ever stop to look at it.

[00:22:31] Kristin Swenson It is a work of propaganda that it celebrates some of what could be the best in us. The acceptance of difference. The recognition that religion may be beyond the ken of any one group or another. And the grace to let people be how and where they are.

[00:23:03] Kurtis Schaeffer It really gets at the heart of what we do as scholars of texts that are hundreds or thousands of years old. How much can you really know about an author's intentions when you have just a few paragraphs of very formal writing. At a certain point do we just have to accept we can never know for sure and make our best argument.

[00:23:22] Mark Hamilton You know when we when we talk about in ancient times we have fragments. There are many, many things we don't know. And we have these precious fragments from which we can find things out. Or, as a friend of mine likes to say — We're looking through a little pinhole into a beautiful garden. But all we have is that little pinhole's perspective.

[00:23:50] Kristin Swenson You asked first about what we do know about Cyrus. One of the things we know is that he established his capital at Pasargadae. Archaeologists have discovered no defenses, but copious gardens formal gardens that all face kind of out. Very open and airy. And so it appears that he did have intention of ruling in a way that didn't anticipate hostility. I do think that he understood — whether it was just shrewd political maneuvering, or a kind of humanitarian ethos — or maybe those are don't have to be separate. He saw the respectful treatment of the people he had conquered — giving them a great deal of liberty — as the way to move forward peacefully and productively.

[00:24:57] Martien Halvorson-Taylor I asked Orly about this. About how we can read so much into this ancient edict. This ancient cylinder...but we just don't know what Cyrus was thinking or intending.

[00:25:09] Orly Minazad So yeah so the first I was like This is all very beautiful and he's amazing and gracious and you know all those good things. When I read it a little bit more closely. Not that he wasn't...not that he didn't, you know, free everybody. But he was also a ruler who took over, you know, a lot of land. So it's not like he was this super meek, you know, idealistic person. And this is this is where I question his intentions. What's he trying to get rid of people. Because he really pushed for them to go back home.

[00:25:45] Orly Minazad You know I've thought about it and I think if it's going to improve the quality of people's lives it really doesn't matter to me. It doesn't because I mean at the end of the day you just want to feel safe. You want to feel like you're home wherever you're living. And if it is propaganda I guess to use it for good instead of evil...it's fine with me.

[00:26:16] Kurtis Schaeffer Sacred and Profane was produced for the Religion, Race and Democracy lab at the University of Virginia. Our senior producer is Emily Gadek. Our program and communications manager is Ashley Duffalo. Our intern is Laura Logan.

[00:26:31] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Today's guests are Mark Hamilton, Orly Minazad, and Kristin Swenson. Additional research for this episode came from Ashley Tate. Our readers were Meghan Hartman, David Vanderhooft, Rosalind Tordesillas, and Rico Gagliano. Music in this episode came from Blue Dot Sessions.

[00:26:52] Kurtis Schaeffer For more on our work, head to religionlab.virginia.edu, or follow us on Twitter @TheReligionLab. And if you like the show, make sure to subscribe, and rate us on the podcatcher of your choice. It really makes a difference for shows like ours that are just starting out.

Just over 2,500 years ago, a victorious army marched through the open gates of the mighty city of Babylon. Soon after came a decree: that all the conquered peoples who had been brought to the city by Babylonian kings — the people who helped build its magnificent temples, gardens, and palaces — could return to their homelands, to worship their own gods as they saw fit.

In the many years since it was written, the edict has been interpreted in many ways: as a sign from God; as the first declaration of human rights; as a savvy piece of political propaganda.

How much do the intentions of the person who wrote it matter, over two millennia later?

The Cylinder, Translated

“I am Cyrus, king of the world, great king, mighty king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters…” Read the rest of the translated cylinder at livius.org.

The Cyrus cylinder today, courtesy of Trustees of the British Museum

How to cite this piece:

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K. (Presenters), & Gadek, E. (Producer). “I Sent The Gods Back.” Sacred & Profane (2019, September 2).

Related Content:

What’s So Great About Cyrus?

Season 2/Episode 7

A look at two very different rulers who have become associated with the Biblical king Cyrus the Great: the last Shah of Iran, and President Donald Trump.

Additional Reading

Hamilton, Mark. W. “Who Was a Jew? Jewish Ethnicity during the Achaemenid Period.” Restoration Quarterly 37 (1995): 102-117.

Harrop, William Scott. “Cyrus and Jefferson: Did They Speak the Same Language?” Middle Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures 13, no. 1 (Spring 2013).

Kohl, Philip L. “Nationalism and Archaeology: On the Constructions of Nations and the Reconstructions of the Remote Past.” Annual Review of Anthropology 27 (1998): 223-46.

Kuhrt, Amélie. “Cyrus the Great of Persia: Images and Realities”. In Heinz, Marlies; Feldman, Marian H. Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2007.

MacGregor, Neil. “2600 Years of History in One Object.” Filmed July 2011. TED video, 19:30. https://www.ted.com/talks/neil_macgregor_2600_years_of_history_in_one_object.

Merhavy, Menahem. “Religious Appropriation of National Symbols in Iran: Searching for Cyrus the Great.” Iranian Studies 49, no. 6 (2015): 933-948.

Minazad, Orly. “What the Cyrus Cylinder at the Getty Villa Means to L.A.’s Iranian Community.” LA Weekly, October 8, 2013.

Swenson, Kristin. Bible Babel: Making Sense of the Most Talked About Book of All Time. HarperCollins, 2010.

Additional Credits

Our guests were Orly Minazad, Mark Hamilton, and Kristin Swenson. Our English readers were Meghan Hartman, Rosalind Tordesillas, and Rico Gagliano. David Vanderhooft read for us in Akkadian.

Illustration by Carson McNamara. Photo of the Cyrus Cylinder courtesy of Trustees of the British Museum.