Sacred & Profane, Season 4, Episode 10

What the Future Holds

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:00:00] I'm Kurtis Schaeffer.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:00:01] And I'm Martien Halvorson-Taylor. And this is Sacred and Profane.

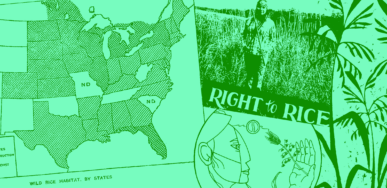

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:00:06] This episode is part of our ongoing series on climate change and religions in the US. We call it between Heaven and Earth. And the big question we're looking at is how religion has shaped the way Americans think about and live on the land, and how the land has shaped religion.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:00:25] Throughout this season, we've talked about the role institutional Christianity has played in some of the foundations of today's climate crisis. And we've also heard how the 20th century environmental movement has deep roots in Protestant thinking about nature and the environment. And that conversation is continuing in the 21st century. We wanted to speak with someone who is thinking deeply about climate change from a religious perspective, and putting that thinking into action.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:00:59] My name is Reverend Mariama White-Hammond. I'm a pastor of New Roots AME church, based in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. Although increasingly we have folks joining us virtually from a lot of other places too. I am a farmer. I have a farm in New Hampshire and, a scuba diver. And I love the world, the earth, nature. And in my day job from all the other things that I do. I'm also, the chief of environment, energy and open space for the city of Boston. So I see myself as a faith leader first. But I also do spend some time in the policy and government realm to.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:01:41] The Reverend White-Hammond's job is part of a broader push from Boston's mayor, Michelle Wu, at a time when federal support for anything to mitigate climate change seemed to be flagging. Wu campaigned on a Green New Deal for Boston and won decisively. The idea behind these policies is that very often social and environmental problems go hand in hand.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:02:03] What we're trying to do is do our climate work in a way that reduces emissions and makes us more climate resilient and improves quality of life for people and a very real and tangible way? As an example, like I live near one of the parks right now, waterfront, and we're looking at a pretty huge redesign of that park, and you're going to be able to play basketball and rugby and have a farmer's market and all these things in this park, and grow your own vegetables, because we'll have some raised beds. So all of these great things that people are going to experience, and it will have a permanent and a bio as and a lot of different things that are set up to protect the community from flooding. And that's particularly important because right behind that park on two sides are two different public housing developments that have been there for years that deserve not to be inundated by sea level rise.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:03:03] We wanted to speak with her, not just about her day job, as she puts it, but the lived theology that undergirds the work that she does. Let's go back to the beginning. She grew up in Boston and was active in her church's youth ministry.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:03:22] I grew up in a charismatic, social justice oriented congregation, which for many people sounds a bit like an oxymoron. Most folks, when they think Pentecostal charismatic, they don't think justice. But that was the context I grew up in. I went to the, preschool attached to my church, and Rosa Parks came to visit our school.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:03:51] By the time she was in high school, White-Hammond was balancing the urgency of two things at once. Violence in her neighborhood, but also the dawning realities of climate change.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:04:04] I remember there was the huge awareness about the hole in the ozone layer. And I think that as a young person that that was kind of mind blowing, the idea that human activity could, could literally affect the stability of the planet. And so, I remember because this was like in the 90s, and I think if folks who remember all those horrible 90s hairdos acquired a lot of hairspray, and I went to an all girls school, and I remember really pushing us around like, we have to move away from these chlorofluorocarbons that are destroying the atmosphere. And, and I went to the meeting of the environmental club. And while I was there, I remember I was the only young person of color. I was only the only young woman of color in the space. And this was in the 90s, at the same time that we were in the height of violence in Boston. I remember sort of having this moment or, I was perplexed by the idea that people could care about dolphins and polar bears that they'd never met or interacted with, but they were not terribly concerned about the issues of violence that were happening in Boston, only miles from our school. And I left that meeting and never went back.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:05:14] It felt like it wasn't possible to get her white classmates to see the connection between caring for what happened in Boston and the environment.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:05:24] And I think I found myself in some of the same conundrum that many communities of color, people who are working on economic justice issues lift up, which is how do I embrace a movement that often is talking about faraway places, embrace a movement that is not aware of the like, very real issues that I'm facing in my life. And I felt myself stuck in that conundrum. So I definitely cared about the issues in the ozone layer. I cared about the environmental issues, but I felt frustrated by this idea that the environmental movement was not aware of, nor oriented to dealing with the many issues we were dealing in my community.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:06:07] Her sense of certainty that these issues were intimately connected only increased after she traveled to New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:06:17] Watching what happened in Hurricane Katrina, having been to New Orleans, having taken young people to New Orleans, because I ran a youth arts and history program, and we would visit New Orleans and visit other groups there. And I watched Hurricane Katrina hit. I knew the neighborhoods that were flooding when the levees broke. I knew I could recognize them as places I had been, and communities that were not altogether different from the community that I grew up in and the communities that I have been organizing in.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:06:46] Katrina was an environmental disaster, but it was also a disaster shaped by human decisions about which neighborhoods were saved and which were sacrificed. A vivid example of environmental racism.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:06:59] There really was a moment that began my quest to understand how do I have this real critique raise my concerns, but also, how can I try to be a voice for a different way of looking at how we address the climate crisis, while simultaneously lifting up all the other justice issues that are deeply entangled in our decisions to exploit the Earth. Our decisions about which communities get the leftover dumping from that exploitation, which communities, don't have access to open space, see their environment degraded, have to deal with polluted water or air or or earth around them. There's a way to approach this that brings all of that together. That's the quest I've been on from being a teenager and to coming to a point where I've said, no one can force me to choose. I will find another way to be engaged without feeling like I have to leave my community behind. From the time I was a child. I have always been taught that God is a God of justice. My formative years, I've never seen a disconnect between my faith and justice work, because I have seen justice work as living out my faith as being in alignment with what God calls me to. So I don't know if, like right after Katrina, if I could have said to you, I could have fully articulated with clarity a theology of environmental justice. But I, I think for me, justice and faith, they always are swimming in the same water.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:08:57] White Hammond says it was her time in seminary where she studied to be ordained as a pastor in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. That gave her the time to think through these issues theologically. She believes this theology can help guide us to a better future.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:09:14] Quite frankly, seminary just gave me a space to breathe and to process all of what I had seen into something that I could share back with people, and an ability to to take a moment to breathe so I could articulate what I felt like God placed in my heart. So here's the way I look at it. For me, it feels so clear that God created the world and said it was good. And the way we are treating the world is not as though it was good that I actually think it hurts God's heart what we're doing, what we're doing to the planet, what we're doing to each other. And I believe another way is possible. Because I think the other thing that holds us back is people's belief that this is the best we can do. And what I say to a lot of my fellow folks of faith, even if we see faith differently, I don't think this is the best God has for us, and I won't settle if I don't think God would settle. And I think God calls us to more. And I want to have a conversation about what that looks like. And you may see it differently than I do. But I want to start from the notion that this way that we're living, it's just not the best we can do. And if we say we believe in an almighty, powerful, world changing God, but we live in the world as though this is the best we can do. I want a question of that is truly indicative of the faith we say we have. So not here to change, but I want to share. That's the way I see the world. And if that sounds resonant to you, I'd love to have even more conversation about what is possible.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:11:17] She says there's also a fine line that any church engaged in environmental justice work has to negotiate, working with people outside your religious tradition.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:11:28] Before I had an official title as a pastor, you know, I grew up in Boston, and so I had built a lot of relationships. I got to work ecumenical with a lot of different folks within the Christian tradition. But a lot of relationships within the Jewish community got to connect with Muslims, Buddhists, like Unitarian, like lots of different traditions. What I hope the faith community will do even more. And something I'm trying to engage in conversation with my congregation about is how do we lead from a place of a faith in a way that doesn't? It's not. We're not proselytizing. People are asking them to change, but we are speaking to the policy that we want from the deepest place of what is possible. And it can be hard to hold both of those. But I think that's what we need, quite frankly, not just from a climate perspective, but because our democracy is also not in the best shape right now.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:12:34] These challenges have not deterred her from discussing the climate crisis from the pulpit.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:12:40] I still feel very much called to be a faith leader because if our will doesn't change, if we don't imagine a different world that we're moving to, we won't mobilize to create it. No small part of that is, we need to imagine who we want to be and change. Humans struggle around change. We'd love for other people to change. We don't want you to tell us to change. We even want the change. But we don't want the like. Pain, and that the discomfort that comes from having to do something that's outside of how you usually do it and what your habits are, right. So we need good policy. I'm excited to do that work. But if we don't have a radical shift in who we are and who we choose to be, we will not use the tools available to us. You can have all the hammers and all the nails and all the planks that you want. If you don't choose to build a house, that stuff is just sitting on the ground. And quite frankly, it'll it'll become inoperable over time if you just leave it out in the elements. Right. You have to put those things together. And that means having a vision, a plan for where you're trying to go and then using the tools that are at your disposal to get there. And so we are still very much in a social, spiritual crisis of imagining who we want to be and getting there.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:14:15] White-Hammond is firm in the idea that we have the tools to create a better future, if we can imagine it. And so we asked her what she envisioned for her own community.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:14:27] Oh, wow. So I see shifts in the way we live in so many different levels. So first of all, I don't think it's sustainable for like two parents in like one and a half or two and a half kids or whatever. I see so many of my friends struggling with like child care. I see people struggling in terms of the amount that they're working. And so I see us living in much more village style, right? Not each separated from each other. I see us making meals together in ways that we don't need to all have five different kitchens going at the same time, but we make collective meals that cut down our energy usage. And guess what? We don't eat alone. We don't eat in front of the TV, we eat together, and as much as possible, we're growing that food on our roofs. Or we're getting it from the farmer's market as locally as we possibly can, following our our food to the seasons, enjoying the fact that our neighbors come from somewhere else and they cook that same item and it's totally different way, and we're excited about the opportunity to go over and help them. I think we live much more locally. We don't always have to travel here, there and everywhere, which allows us to be far more present in our communities. We don't commute as much to get to work. I think we are doing a lot more remote work, but we're also building a lot more small local businesses that we can walk to work more. And in all of that, not only are we using significantly less energy driving and using a lot less energy cooking and maximizing the number of people in a house so that we are not tearing down forest to build new houses. In all of that, we are also so much more connected. And when we get to a point where we feel down, we don't have to worry that we will not get noticed and that will just continue to struggle by ourselves because people know us. And they watch out for us. And we do that together. And we may go to different congregations whatever day we worship, but we feel really connected and we feel like in addition to whatever tradition, religious tradition, we're part of the community that we live in. Really grounds us. We are not alone.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:17:26] Sacred and Profane was produced for the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia. This episode was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Our senior producer is Emily Garrick. Our guest is the Reverend Mariama White-Hammond.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:17:44] Music for this episode comes from blue Dot sessions. You can find out more about our work at Religion lab.virginia.edu.

What the Future Holds

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:00:00] I'm Kurtis Schaeffer.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:00:01] And I'm Martien Halvorson-Taylor. And this is Sacred and Profane.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:00:06] This episode is part of our ongoing series on climate change and religions in the US. We call it between Heaven and Earth. And the big question we're looking at is how religion has shaped the way Americans think about and live on the land, and how the land has shaped religion.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:00:25] Throughout this season, we've talked about the role institutional Christianity has played in some of the foundations of today's climate crisis. And we've also heard how the 20th century environmental movement has deep roots in Protestant thinking about nature and the environment. And that conversation is continuing in the 21st century. We wanted to speak with someone who is thinking deeply about climate change from a religious perspective, and putting that thinking into action.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:00:59] My name is Reverend Mariama White-Hammond. I'm a pastor of New Roots AME church, based in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. Although increasingly we have folks joining us virtually from a lot of other places too. I am a farmer. I have a farm in New Hampshire and, a scuba diver. And I love the world, the earth, nature. And in my day job from all the other things that I do. I'm also, the chief of environment, energy and open space for the city of Boston. So I see myself as a faith leader first. But I also do spend some time in the policy and government realm to.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:01:41] The Reverend White-Hammond's job is part of a broader push from Boston's mayor, Michelle Wu, at a time when federal support for anything to mitigate climate change seemed to be flagging. Wu campaigned on a Green New Deal for Boston and won decisively. The idea behind these policies is that very often social and environmental problems go hand in hand.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:02:03] What we're trying to do is do our climate work in a way that reduces emissions and makes us more climate resilient and improves quality of life for people and a very real and tangible way? As an example, like I live near one of the parks right now, waterfront, and we're looking at a pretty huge redesign of that park, and you're going to be able to play basketball and rugby and have a farmer's market and all these things in this park, and grow your own vegetables, because we'll have some raised beds. So all of these great things that people are going to experience, and it will have a permanent and a bio as and a lot of different things that are set up to protect the community from flooding. And that's particularly important because right behind that park on two sides are two different public housing developments that have been there for years that deserve not to be inundated by sea level rise.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:03:03] We wanted to speak with her, not just about her day job, as she puts it, but the lived theology that undergirds the work that she does. Let's go back to the beginning. She grew up in Boston and was active in her church's youth ministry.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:03:22] I grew up in a charismatic, social justice oriented congregation, which for many people sounds a bit like an oxymoron. Most folks, when they think Pentecostal charismatic, they don't think justice. But that was the context I grew up in. I went to the, preschool attached to my church, and Rosa Parks came to visit our school.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:03:51] By the time she was in high school, White-Hammond was balancing the urgency of two things at once. Violence in her neighborhood, but also the dawning realities of climate change.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:04:04] I remember there was the huge awareness about the hole in the ozone layer. And I think that as a young person that that was kind of mind blowing, the idea that human activity could, could literally affect the stability of the planet. And so, I remember because this was like in the 90s, and I think if folks who remember all those horrible 90s hairdos acquired a lot of hairspray, and I went to an all girls school, and I remember really pushing us around like, we have to move away from these chlorofluorocarbons that are destroying the atmosphere. And, and I went to the meeting of the environmental club. And while I was there, I remember I was the only young person of color. I was only the only young woman of color in the space. And this was in the 90s, at the same time that we were in the height of violence in Boston. I remember sort of having this moment or, I was perplexed by the idea that people could care about dolphins and polar bears that they'd never met or interacted with, but they were not terribly concerned about the issues of violence that were happening in Boston, only miles from our school. And I left that meeting and never went back.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:05:14] It felt like it wasn't possible to get her white classmates to see the connection between caring for what happened in Boston and the environment.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:05:24] And I think I found myself in some of the same conundrum that many communities of color, people who are working on economic justice issues lift up, which is how do I embrace a movement that often is talking about faraway places, embrace a movement that is not aware of the like, very real issues that I'm facing in my life. And I felt myself stuck in that conundrum. So I definitely cared about the issues in the ozone layer. I cared about the environmental issues, but I felt frustrated by this idea that the environmental movement was not aware of, nor oriented to dealing with the many issues we were dealing in my community.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:06:07] Her sense of certainty that these issues were intimately connected only increased after she traveled to New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:06:17] Watching what happened in Hurricane Katrina, having been to New Orleans, having taken young people to New Orleans, because I ran a youth arts and history program, and we would visit New Orleans and visit other groups there. And I watched Hurricane Katrina hit. I knew the neighborhoods that were flooding when the levees broke. I knew I could recognize them as places I had been, and communities that were not altogether different from the community that I grew up in and the communities that I have been organizing in.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:06:46] Katrina was an environmental disaster, but it was also a disaster shaped by human decisions about which neighborhoods were saved and which were sacrificed. A vivid example of environmental racism.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:06:59] There really was a moment that began my quest to understand how do I have this real critique raise my concerns, but also, how can I try to be a voice for a different way of looking at how we address the climate crisis, while simultaneously lifting up all the other justice issues that are deeply entangled in our decisions to exploit the Earth. Our decisions about which communities get the leftover dumping from that exploitation, which communities, don't have access to open space, see their environment degraded, have to deal with polluted water or air or or earth around them. There's a way to approach this that brings all of that together. That's the quest I've been on from being a teenager and to coming to a point where I've said, no one can force me to choose. I will find another way to be engaged without feeling like I have to leave my community behind. From the time I was a child. I have always been taught that God is a God of justice. My formative years, I've never seen a disconnect between my faith and justice work, because I have seen justice work as living out my faith as being in alignment with what God calls me to. So I don't know if, like right after Katrina, if I could have said to you, I could have fully articulated with clarity a theology of environmental justice. But I, I think for me, justice and faith, they always are swimming in the same water.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:08:57] White Hammond says it was her time in seminary where she studied to be ordained as a pastor in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. That gave her the time to think through these issues theologically. She believes this theology can help guide us to a better future.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:09:14] Quite frankly, seminary just gave me a space to breathe and to process all of what I had seen into something that I could share back with people, and an ability to to take a moment to breathe so I could articulate what I felt like God placed in my heart. So here's the way I look at it. For me, it feels so clear that God created the world and said it was good. And the way we are treating the world is not as though it was good that I actually think it hurts God's heart what we're doing, what we're doing to the planet, what we're doing to each other. And I believe another way is possible. Because I think the other thing that holds us back is people's belief that this is the best we can do. And what I say to a lot of my fellow folks of faith, even if we see faith differently, I don't think this is the best God has for us, and I won't settle if I don't think God would settle. And I think God calls us to more. And I want to have a conversation about what that looks like. And you may see it differently than I do. But I want to start from the notion that this way that we're living, it's just not the best we can do. And if we say we believe in an almighty, powerful, world changing God, but we live in the world as though this is the best we can do. I want a question of that is truly indicative of the faith we say we have. So not here to change, but I want to share. That's the way I see the world. And if that sounds resonant to you, I'd love to have even more conversation about what is possible.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:11:17] She says there's also a fine line that any church engaged in environmental justice work has to negotiate, working with people outside your religious tradition.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:11:28] Before I had an official title as a pastor, you know, I grew up in Boston, and so I had built a lot of relationships. I got to work ecumenical with a lot of different folks within the Christian tradition. But a lot of relationships within the Jewish community got to connect with Muslims, Buddhists, like Unitarian, like lots of different traditions. What I hope the faith community will do even more. And something I'm trying to engage in conversation with my congregation about is how do we lead from a place of a faith in a way that doesn't? It's not. We're not proselytizing. People are asking them to change, but we are speaking to the policy that we want from the deepest place of what is possible. And it can be hard to hold both of those. But I think that's what we need, quite frankly, not just from a climate perspective, but because our democracy is also not in the best shape right now.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:12:34] These challenges have not deterred her from discussing the climate crisis from the pulpit.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:12:40] I still feel very much called to be a faith leader because if our will doesn't change, if we don't imagine a different world that we're moving to, we won't mobilize to create it. No small part of that is, we need to imagine who we want to be and change. Humans struggle around change. We'd love for other people to change. We don't want you to tell us to change. We even want the change. But we don't want the like. Pain, and that the discomfort that comes from having to do something that's outside of how you usually do it and what your habits are, right. So we need good policy. I'm excited to do that work. But if we don't have a radical shift in who we are and who we choose to be, we will not use the tools available to us. You can have all the hammers and all the nails and all the planks that you want. If you don't choose to build a house, that stuff is just sitting on the ground. And quite frankly, it'll it'll become inoperable over time if you just leave it out in the elements. Right. You have to put those things together. And that means having a vision, a plan for where you're trying to go and then using the tools that are at your disposal to get there. And so we are still very much in a social, spiritual crisis of imagining who we want to be and getting there.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:14:15] White-Hammond is firm in the idea that we have the tools to create a better future, if we can imagine it. And so we asked her what she envisioned for her own community.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond [00:14:27] Oh, wow. So I see shifts in the way we live in so many different levels. So first of all, I don't think it's sustainable for like two parents in like one and a half or two and a half kids or whatever. I see so many of my friends struggling with like child care. I see people struggling in terms of the amount that they're working. And so I see us living in much more village style, right? Not each separated from each other. I see us making meals together in ways that we don't need to all have five different kitchens going at the same time, but we make collective meals that cut down our energy usage. And guess what? We don't eat alone. We don't eat in front of the TV, we eat together, and as much as possible, we're growing that food on our roofs. Or we're getting it from the farmer's market as locally as we possibly can, following our our food to the seasons, enjoying the fact that our neighbors come from somewhere else and they cook that same item and it's totally different way, and we're excited about the opportunity to go over and help them. I think we live much more locally. We don't always have to travel here, there and everywhere, which allows us to be far more present in our communities. We don't commute as much to get to work. I think we are doing a lot more remote work, but we're also building a lot more small local businesses that we can walk to work more. And in all of that, not only are we using significantly less energy driving and using a lot less energy cooking and maximizing the number of people in a house so that we are not tearing down forest to build new houses. In all of that, we are also so much more connected. And when we get to a point where we feel down, we don't have to worry that we will not get noticed and that will just continue to struggle by ourselves because people know us. And they watch out for us. And we do that together. And we may go to different congregations whatever day we worship, but we feel really connected and we feel like in addition to whatever tradition, religious tradition, we're part of the community that we live in. Really grounds us. We are not alone.

Kurtis Schaeffer [00:17:26] Sacred and Profane was produced for the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia. This episode was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Our senior producer is Emily Garrick. Our guest is the Reverend Mariama White-Hammond.

Martien Halvorson-Taylor [00:17:44] Music for this episode comes from blue Dot sessions. You can find out more about our work at Religion lab.virginia.edu.

We started our series with an exploration of how religious doctrine and belief became deeply entwined with both colonialism and the petroleum industry. We followed the stories of contemporary Americans whose religious beliefs — and beliefs about climate — shape their determination to stop pipelines and restore local ecosystems. But what about our future? We spoke with the Rev. Mariama White-Hammond about climate justice, and her hopes for a new vision where care for our neighbors and care for the environment go hand in hand.

Additional Credits

This episode was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Special thanks to Erin Burke, Rebecca Bultman, and Devin Zuckerman for their help on this episode.

Subscribe