[00:00:07] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Welcome to Sacred and Profane. I'm Martien Halvorson-Taylor.

[00:00:11] Kurtis Schaeffer And I'm Kurtis Schaeffer.

[00:00:20] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Together with students and faculty here at UVA, we're exploring how religion plays out in our daily lives in the obvious and in the less obvious ways. How religion influences what and how we think of ourselves as people and as citizens. And how we shape and are shaped by religion, sometimes at the same time.

[00:00:50] Kurtis Schaeffer On today's show we're focusing on a group of people struggling with a choice that puts their religious practice in conflict with political and economic realities shaping the world around them. It's a story that starts in the mountains of West Virginia. The community sits right on top of two rock formations, where huge deposits of natural gas are being extracted by fracking - that is, driving pressurized water deep into the rock to bring up the gas. It's a lucrative business, but also one that can bring environmental problems.

[00:01:22] Martien Halvorson-Taylor They're trying to figure out how to maintain their way of life and their religious practice with the extraction efforts underway all around them.

[00:01:31] Martien Halvorson-Taylor We want to tell this story because it captures how people negotiate their various overlapping identities religious economic political which don't always peacefully coexist. This community has been struggling financially for a long time, and the decision to allow fracking on their land has helped them to grow. But at the same time, it would seem to go against all the reasons they came to West Virginia and began this community in the first place - to pursue plain living and high thinking. To get away from it all. To return to the land.

[00:02:14] Molly Born So we're walking off to the barn.

[00:02:18] Molly Born It's January before sunrise. It's really cold - that is snow crunching under our feet.

[00:02:21] Martien Halvorson-Taylor That's Molly Born. She's a reporter from West Virginia who's been following this story for years and she's looking into this with Kevin Rose, a graduate student here at UVA who's researching how religious communities think about resource extraction like the fracking that's taking place across Appalachia.

[00:02:34] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Hey Kevin.

[00:02:] Kevin Rose Hey Martien. Hey Kurtis.

[00:02:53] Kurtis Schaeffer Kevin, Molly, welcome to the show.

[00:03:00] Worship the cow, it's like, a holy animal in Indian tradition. So, we’re ready.

[00:03:16] Molly Born As we're standing there, eight cows wander into the barn.

[00:03:20] Molly Born Each day, community members bring each cow offerings of spices and fruit. They feed them bananas, and gently brush each one before they're milked. This practice is all about honoring the cows, showing appreciation for their bounty. The leadership says when they treat the cows in a loving way, their personalities come out.

[00:03:41] Molly Born Just about a half mile away from these stalls is a construction site.

[00:03:45] Molly Born After years of negotiation and prep work, a well will soon be drilled deep into the rock beneath this community to allow a company called American Petroleum Partners access to one of two enormous natural gas fields. How and why that well came to be drilled on land dedicated to serving the Hindu god Krishna? Well, that's a long story.

[00:04:07] Molly Born Let's start with the Krishna side of things.

[00:04:16] Kevin Rose These cows, and more than 200 people are living in and around a commune in the northern panhandle of West Virginia, about 70 miles southwest of Pittsburgh. It's called New Vrindaban, after the holy city in India where the Hindu god Krishna spent much of his childhood. And Krishna and cows go together. He's often depicted as a young cow herd, and his followers believe he can appear in the form of a cow. So cow protection, that is to say giving these cows are good and happy life, is a key part of life in New Vrindaban.

[00:04:52] Molly Born Members view living in close connection with the land and the cattle as following an ideal laid out in ancient Indian scriptures, an ideal that has been lost in modern life. New Vrindaban founders believe that living in the industrialized 20th century was corrupt and soul killing. The antidote was plain living and high thinking, that is, to live in harmony with the environment. To live simply, and by doing that, coming closer to the divine.

[00:05:15] Lalita Gopi I think that the whole earth is sacred, you know?

[00:05:25] Molly Born This is Lalita Gopi. She and her husband work for the non-profit here that's dedicated to cow protection and locally grown agriculture.

[00:05:36] Lalita Gopi And different avenues, one protected area that was bought with the intention of keeping it extra sacred. You know, like an oasis, like a place for people to come and remember the sacredness of the whole earth.

[00:05:45] Kevin Rose This philosophy comes from the larger organization they're a part of - the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, more commonly known as Hari Krishnas.

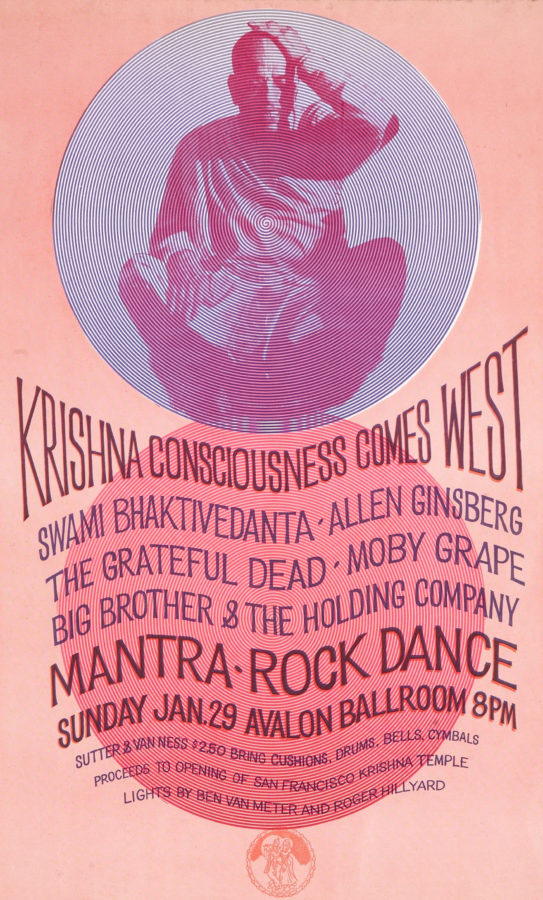

[00:06:00] Molly Born That's shorthand comes from a mantra that believers chant when they worship, repeating the names of Krishna. The movement's founder, Sheila Prabhupada, is 70 years old when he sailed from India to New York in 1965 and brought this new Hindu movement along with them. He started preaching in New York soon after he arrived. But things really took off when he moved to San Francisco.

[00:06:12] Kevin Rose At the time, the city was the center of the counterculture full of people experimenting with almost everything: free love, drugs, and new ways of living.

[00:06:24] Tape This is a Krishna kirtan, conducted by A. C. Bhaktivedanta in a storefront near Keysar stadium. The standard Judeo-Christian morals are done for, they’ve flown the coop. One of the things these young people are interested in is the quality of being holy, the kirtan, the mantra singing.

[00:06:58] Kevin Rose And Prabhupada and his followers weren't afraid to put things in terms that would appeal to San Francisco's hippies. There was even a Hari Krishna poster that read: "Stay high forever. No more coming down. Practice Krishna Consciousness."

[00:07:15] Kevin Rose That's not to say that the Hari Krishna movement advocated sex, drugs, and rock n' roll. Serious devotees had to change their lifestyles. They abstained from meat alcohol, tobacco, and sex outside marriage. And they were expected to live for a while in an ashram, like the one at New Vrindaban.

[00:07:35] Gabriel Freed And everything we did, we did a service. We did for the Lord, we did for the pleasure of Srila Prabhupada. That was our goal, that was our motivation.

[00:07:46] Molly Born That's Gabriel Freed. He moved to New Vrindaban nearly 40 years ago. Members were still building homes and learning how to farm. It wasn't always comfortable.

[00:07:55] Gabriel Freed My wife and I would be laying on the floor in our sleeping bags, and I've got this big wood stove, it's glowing red it's so hot! But not enough to actually really heat the place very well, because it's essentially a trailer with no insulation. So we, would haul our water in buckets and bring it over to the house. Everything was mud. This place was known for its mud, you could lose a shoe in mud.

[00:08:26] Molly Born It may not have been comfortable, but it was exactly what Trilla Prabhupada had in mind for New Vrindaban. He urged his followers to live as simply as possible, to live a natural, healthy life without modern amenities. The kind of life that would be difficult in New York or San Francisco. And Gabriel Freed's says despite the austerity, or maybe because of it, those years were filled with dynamic energy.

[00:08:48] Gabriel Freed And there was such an intense camaraderie and love. Just like in any other situation, people who go to war together, and they go through an intense experience and they have the austerity of going through battle. They're bonded - they're bonded for life.

[00:09:16] Leila Shukadasi I have a lot of friends here know after I've been here for a little while. A whole bunch of us we all had our first kids at the same time, you know, like we helped each other watch our kids. So it was a real, there was a real sisterhood and brotherhood, also

[00:09:29] Molly Born Leila Shukadsi and her husband were members of a Hari Krishna temple in Toronto when they moved to the Ashram in 1980 looking for a simpler life.

[00:09:39] Leila Shukadasi. It was really wonderful, actually, and we were all growing in Krishna Consciousness. We were really helping each other, and that's the kind of thing I've been craving, you know, a lot in my life. Some kind of real support and a real loving community. And that's what I found.

[00:09:58] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So how did the community end up in West Virginia in the first place?

[00:10:03] Molly Born It all started with a letter from this mystic philosopher named Richard Rose. He sent it to an underground newspaper in San Francisco offering up some of his land for people to practice their religion freely.

[00:10:15] Molly Born Two Hari Krishna devotees saw the letter, and got a 99 year lease on more than 100 acres of land. Remember while Sheila Prabhupada was recruiting new followers in cities, he believed the country could offer a simpler life, free of modern distractions like movies or nightclubs. It seemed a perfect fit.

The idea was the followers would start a farming community that would eventually be self-sufficient.

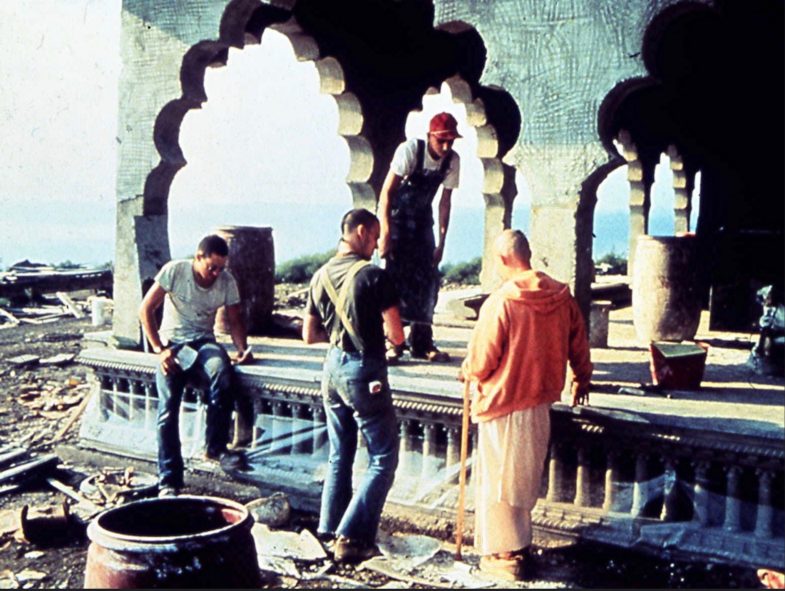

[00:10:42] Kevin Rose Members did more than farm. They also started building a home for Prabhupada, where he could stay during visits to the cottage. Many were unskilled, but they say they had Krishna's guiding hand to help them build what would become one of the most iconic emblems of the movement in a pilgrimage destination for followers from around the world. It's called the Palace of Gold.

[00:11:05] Molly Born I grew up not far from New Vrindaban and I can tell you I've never seen anything like it. I first visited as a kid with my parents. It really is spectacular

[00:11:44] Molly Born In the winter when Kevin and I visited, you have these mountains all around. There's some snow, the trees are bare, and up on the hill you just see this beautiful jewel box. It's lined with intricate stained glass windows, and it's covered in gold leaf. It's the most colorful thing for miles. It seems wild that it's in the hills of West Virginia.

[00:12:00] Kevin Rose It really is a beautiful spot. But from the beginning, New Vrindaban has struggled to sustain itself. At its height in the 1980s, about 400 people lived here, which made it the largest Hari Krishna community in the United States. But this land was wild and rural. Farming was difficult. Prabhupada had also wanted New Vrindaban to become a pilgrimage site, and building the attractions that would get people to come was expensive.

[00:12:20] Molly Born New Vrindaban was also facing serious new problems by the mid 80s. The current leader calls this period "The Troubles." It's part of the history that some here would rather not dwell on, but it's hard to ignore. New Vrindaban's leader at that time was Swami Bhaktipada, and he was accused of sexually abusing and exploiting children. And of ordering the murders of two of his followers who defied him.

[00:12:49] Kevin Rose All of this had serious consequences for New Vrindaban, and Bhaktipada was eventually excommunicated from the international governing body, and the community was disgraced in the eyes of the larger movement. By the late nineties, there were only a few dozen people living in New Vrindaban, and it had become harder to attract new members after Swami Bhaktipada had been exposed. Those that stayed, like Leila Shukadasi, remember it as a time of reckoning

[00:13:00] Leila Shukadasi In lot of ways, it was, uh, a cohesive factor within the community also. We had to re-evaluate what is Khrishna Consciousness anyhow? What am I doing here, and what do I want out of this?

[00:13:20] Molly Born It wouldn't be the last time the community had to ask hard questions about its identity. It turned out that New Vrindaban was located right on top of not one, but two huge natural gas fields. Fields that were finally able to be tapped via fracking. It was a topic of debate not just a New Vrindaban, but throughout the larger Hari Krishna community.

[00:13:56] Leila Shukadasi The devotees here, they consulted with many other HRI Christian devotees around the world, and different people said different things. Some said "Yes we think that our spiritual master Pravabada would take this as a boon, as a benediction, as a blessing." And other people would be like "Are you kidding? Pravabada spoke against having industry anywhere near the area as much as possible." And there's you know there was a lot of money involved, so it was, uh, hard to resist. You know?

[00:14:27] Molly Born This is just a new chapter in an old story. West Virginia has been defined by energy extraction, whether that's natural gas, coal, or timber, for hundreds of years. In fact, the first commercial coal mine in the state was opened in 1810, just ten miles down the road from where New Vrindaban is now.

[00:14:49] Molly Born These industries bring jobs, well-paying but certainly dangerous. And they also bring environmental consequences, even devastation. In coal extraction, whole mountaintops can be removed. Fracking sends natural gas into aquifers, often tainting the water supply. Trees are cut down to make way for equipment and roads.

[00:15:09] Leila Shukadasi Knowing that they would start ripping apart the beautiful countryside... It's so beautiful here. It was kind of almost untouched, I mean really. Wild, wonderful West Virginia. It's like, you know, the Joni Mitchell song - "they paved paradise and put up a parking lot." That just reminds me of that.

[00:15:20] Leila Shukadasi We're trying to minimize. All I think a person could do is minimize, uh, their footprint, they call it. On the Earth. This whole gas thing is the opposite of that. It's just greed, like gone wild.

[00:15:42] Kevin Rose No matter your beliefs, it can be difficult for locals to hold out when energy companies expand. Especially if your neighbours have sold their rights. Once extraction companies build wells on your neighbor's land, they can gain legal access to the resources underlying your land too. Think of the classic "I drink your milkshake" metaphor from There Will Be Blood.

[00:16:06] Gabriel Freed This is a juggernaut, and it's on its way, and it's happening. What can we do to protect ourselves? Because the drilling is coming. We are not going to stop this.

[00:16:15] Molly Born Gabriel Freed has ended up being the liaison between the gas companies and New Vrindaban. He wasn't really assigned to do it; he just kind of stepped up to the plate. He's a welder, and he used to work for a gas company. He could speak the language, and he saw how many of their neighbors had already sold their rights to gas companies, often on terms he described as "lousy." He says the companies were paying landowners pennies on the dollar, and had nothing in place to prevent noise or water pollution.

[00:16:44] Gabriel Freed We found out over 50 percent of the area was already leased with these very bad contract,s and we thought "Can we put together a lease and language that will protect the land, will protect the water?"

[00:17:00] Kevin Rose Ultimately, the leadership decided to sell the mineral rights for hydraulic fracturing.

[00:17:06] Gabriel Freed We looked at everything, and we said, "Okay, here are potentially four places you can drill." We picked areas that would have the lowest impact because, had we not done that and had it all been fractured, uh, as it was with all of the people around us, we would have ended up with a lot more drill sites, a lot more traffic, and a lot more disturbance to the lands.

[00:17:34] Kevin Rose So far the Hari Krishna community has made eight million dollars. Most of that just in signing bonuses. The drilling hasn't begun just yet.

[00:17:44] Gabriel Freed I mean there had to have been a couple of times where I questioned, you know, is this is this just too painful to Mother Earth? Am I being a brute?”

But I have to say, we really looked at this in such depth and from so many different angles. And ultimately, we can see that what we did, we can look back now and said "yes, this was the right decision." Because had we not done this, we would have been taking severe advantage of.

[00:18:34] Kevin Rose The money they've received has been poured back into New Vrindaban, particularly the fading Palace of Gold. Members have been using the signing bonus to restore it.

[00:18:42] Vrindaban Palika During the summer, when the sun is filtering to these beautiful windows, you know? Very nice here.

[00:18:51] Kevin Rose Vrindaban Palika agreed to give us a tour of the palace. She's 67, grew up in East Africa, and moved to New Vrindaban after living in Dallas for several years. We talked about improvements to the complex. There's new apartments for residents, and they fixed up the ornate wall around the palace. We also talked to her about the drilling that made it all possible.

[00:19:13] Vrindaban Palika So don't get caught up so much with the drilling, because in order to survive, we have to do this. I'm not in management. I don't have to run the place. I don't have to worry about paying the bills. So who am I to make questions and judge them? Now see, the thing is that the drilling is going on, therefore they have money. Now they are making all these renovations.

[00:19:41] Molly Born She referenced this era in human history that community members believe we're in right now.

[00:19:48] Vrindaban Palika And really, with the Kali Yuga, we don't have many, many opportunities. Because as Kali Yuga progresses, there will be less and less temples.

[00:19:55] Molly Born Kevin, can you shed some light on this?

[00:19:58] Kevin Rose Yes, so various forms of Hinduism conceptualize time in this cycle of four eras. And the one we're in now, the Kali Yuga, is an inherently corrupt one. To some, there's a sense that no individual action could change this awful time we live in. The awfulness has been preordained.

[00:20:17] Martien Halvorson-Taylor So it seems like there's an unspoken tension here. on the one hand they want to live lightly on the earth, and on the other hand they have this more fatalistic view that these aren't good days.

[00:20:25] Vrindaban Palika That is what Krishna wants. I think they are just trying to make the best of the bad bargain. And it's a bad bargain, you know?

[00:20:40] Kevin Rose We heard that phrase over and over. Best of a bad bargain.

[00:20:54] Kurtis Schaeffer In a way you could say that's the big ethical issue in Hinduism, and many other religious traditions. If the world is corrupt, how can you live a life that is not corrupt? How can you be good to other people, to animals, or to the Earth if you're stuck with a bad bargain from the beginning.

[00:21:13] Kevin Rose One answer for the people that live here is to put the money into something they think will last: New Vrindaban and the Palace of God. Vrindaban Palika, the woman we talked to in the palace, she's right. They have been able to do a lot of major repairs. The wall outside the Palace of Gold got a major facelift. They have built new guest lodging, a yoga retreat area. Apartments are being planned. All things that are pointing to a new future for the community. The leadership says visitor numbers and membership are on a steady rise. They've spent almost all of the 8 million dollar signing bonus, and more money will come once drilling begins.

[00:21:51] Kurtis Schaeffer So I have to imagine it's hard to provide protection for cows, or to lead a yoga retreat with all those trucks in the background.

[00:22:00] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Right, in that scenario you can see both sides of the bad bargain. On the one hand they're getting the money they need. But on the other hand, they're losing the very tranquility t.

[00:22:16] Molly Born No, it's a good point. But the community has been able to force the extraction industry to respect at least some of its boundaries.

[00:22:22] Kevin Rose. Followers say the workers have been friendly and respectful to them, and the companies have honored the community's requests to minimize traffic during holy times. Devotees were able to hold a special sacrifice in honor of the trees that were cut down to make way for the pipeline.

[00:22:32] Molly Born There's no doubt the money that fracking has brought in has helped to stabilize the community.

[00:22:37] Molly Born We went to the temple for the 5:00 AM kirtan. It's part of the daily worship service, and on this day there were about two dozen devotees reciting the Hari Krishna mantra.

[00:22:48] Kevin Rose Running the temple takes effort. It's an ornate space, with several shrines to Krishna and one to the group's founder Prabhupada. Devotees dress the deities each day, and there's a special dressing room with hundreds of outfits and pieces of jewelry for them. The community also spends tens of thousands of dollars each year on fresh flowers to adorn them.

[00:23:09] Molly Born We sat down with the temple president, Jaya Krishnadas in his office. He's Swiss, and he came to New Vrindaban from Belgium to lead the community. He said something that was really striking to both of us.

[00:23:22] Jaya Krishnadas For me it's a natural gift of God, that we have these natural resources in New Vridaban. I came to the conclusion that yeah, actually, it's a gift of Krishna. And it's maybe the one reason why New Vrindhaban was created in this place. Which, in North America, it's so big! He could have created New Vrindhaban in so many other places. Maybe much more favorable for growing food, tending cows... But that is one reason that we ended here. There may be many reasons but, speculating, this could be one of the reasons you know.

[00:23:58] Kevin Rose Yeah, he basically said they'll be able to develop the community in the way their founder envisioned much faster with these profits.

[00:26:43] Jaya Krishnadas I think it helps us. These funds, they help us to develop New Vrindhaban, in the way our founders given us the instructions much quicker. And this in itself, attracts more members, new people, and to have regular meetings and discussions, um, helps for sure to keep high awareness of sanctity of this place and respect for for what our founder has created here. But I, I can understand and members of our society and outsiders who are really skeptical that this exploration. That's legitimate that somebody will not like to do move for you.

[00:24:33] Kurtis Schaeffer I hear Jaya Krishnadas being very down to earth about his choice here. The fracking was inevitable, and it was unclear if the community would survive, especially if it decided to hold fast to its environmental ethic to such an extent that it resisted fracking altogether.

[00:24:50] Kevin Rose Yeah, I think that's right. And even, even him, as the most positive of all the people we spoke to, saying this is a gift from Krishna, in all our conversations we saw that, that work happening, how are we going to interpret this with the religious resources we have to make it meaningful,to sort of sustain our purpose, or be able to carry our purpose as a community for.

[00:25:20] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Yeah, I mean, I think that's what's so interesting about this whole thing, and not unlike what a lot of communities struggle with. Actually that's another question I had for you, Kevin. How is this like or unlike other communities that are facing similar issues? Do you see sort of some of the reasoning resonating across religious lines?

[00:25:35] Kevin Rose I do. I think that the resonance is the way in which there's a sort of general sense of people feeling like it's out of our hands. We have to work within this existing political economy. There, there's nothing we can do to sort of overcome that. So we have to find ways to establish some patterns of faithfulness according to our religious traditions. So there's this environmental institute in Michigan called Au Sable Institute. That's become sort of the main center for evangelical theology on the environment. And they discovered oil on their land in 1975, and view it as sort of God's intervention or God's plan in their history, and then the oil let them become this national institute to produce all this evangelical environmental theology. So for them it's similar to what Jaya says like this. Like, this is maybe why we were placed on this land by God, so we could discover this oil.

[00:26:31] Kurtis Schaeffer I wonder if Jaya Krishnadas's message here helps them to prepare for that eventuality. He tells a new story about how they got to be there, and the rightness of them being there. And he also gives them a sense of greater purpose, that allows people to bear with the sacrifices that they all feel they made.

Let me ask you, Molly, as a person who is from this part of the world, do you feel sympathy for the conundrum that these folks in New Vrindaban find themselves?

[00:27:10] Molly Born That's what we talked about earlier, sort of a "tale as old as time." The new extractive forces at play in West Virginia. Yeah, I mean I see that here. I think I think of my own friends and people I know in my community who have had to wrestle with those decisions as well about whether or not to give up these mineral rights. So, I guess, I came to it thinking, um, knowing people who have put up knowing that there's a lot at stake, and knowing people who've had to make that decision for their own families. I can't imagine having to make that decision for the future of a place, that, you know we have to remember this is a holy site. This is a pilgrimage site. People come here from all over the world. They experience something here, it is a special place. They believe it is worth saving. And, you know, if the only way to do that is the only way to afford that and advance that is to is to enter into these agreements. I know, I think it's a strong argument now.

[00:27:45] Kurtis Schaeffer And it's a way to actively interpret what's happening. In the wake of the fracking, they hear Krishna's message differently. So where does this leave us?

[00:28:05] Molly Born For a little while longer, active drilling is a thing of the future. And back in the barn the cows need feeding, milking, and affection every day.

[00:28:12] Molly Born On our visit, Lalita Gopi was milking cows with her husband. The well down the road is never far from them.

[00:28:36] Lalita Gopi It is much harder to live here. You know, it really took a big toll. This is a place of nature, and people connected to the earth and farming. And so,it was, just like, "oh no!" You know, everybody is very, very torn up about it.

[00:28:54] Molly Born But she was hopeful for the future.

[00:28:57] Lalita Gopi And I have faith that we can live through it, you know, we can get through this short time in history. And this will remain a holy place for hopefully thousands of years, you know.

[00:29:05] Kurtis Schaeffer Sacred and Profane was produced for the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia. Our senior producer is Emily Gadek, and our Program and Communications Manager is Ashley Duffalo.

[00:29:19] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Today's show was reported by Molly Born and Kevin Rose. You can find more of Molly's work on Twitter at molly_bo. Music in this episode came from Jazzar and Blue Dot sessions. For more on our work, head to religionlab.virginia.edu or follow us at @thereligionlab on Twitter.

West Virginia has been shaped by resource extraction for hundreds of years. First came timber, then coal. These days, extraction companies are also driving water deep underground to bring up natural gas trapped deep in the rock —in a process known as hydraulic fracking.

These industries bring jobs — well paying, but often dangerous. They also bring environmental consequences, and hard choices for residents. When companies come asking to buy your mineral rights, do you take the money, or do you turn them down?

That’s the question the residents of New Vrindaban have had to answer. The commune is home to a group of Hare Krishna devotees who came to West Virginia starting in the 1970s, intending to start a self-sufficient farming community.

On one level, fracking would seem to go against their reasons for coming to West Virginia in the first place: to return to the land, and live a simple life. The founder of the movement, Srila Prabhupada, believed strongly the country provided protection from the distractions of modern life. And fracking could destroy the tranquility that helped make New Vrindaban not just a working farm, but a pilgrimage site for Hare Krishna devotees from around the world. But the money could also help ensure New Vrindaban’s future as a holy site for decades to come.

UVA doctoral candidate Kevin Rose and reporter Molly Born went to New Vrindaban to find out how the community came to a decision about how — and if — fracking should be allowed on their land.

How to cite this episode:

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K (Presenters), Born, M., Rose, K. (Reporters), & Gadek, E. (Producer). “What Would Krishna Do?” Sacred & Profane (2019, August 19).

Corrections

The original audio of this episode misstated a form of the god Krishna, as well as the number of people living in New Vrindaban in the 1990s. We regret the errors.

Additional Reading

Born, Molly and Litvak, Anya. “The palace that gas rebuilt: Hare Krishnas welcome drilling.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 13, 2015.

Gould, Rebbeca Kneale. At Home in Nature: Modern Homesteading and Spiritual Practice in America. University of California Press, 2005.

Rochford, E. Burke Jr. “Knocking on Heaven’s Door: Violence, Charisma, and the Transformation of New Vrindaban” Violence and New Religious Movements, ed. By James R. Lewis, Oxford Online Scholarship, 2011.

Rose, Kevin Stewart. “Lotuses in Muddy Water: Fracked Gas and the Hare Krishnas at New Vrindaban, West Virginia.” American Quarterly, Volume 72, Number 3, September 2020, pp. 749-769.

An interview with Srila Prabhupada.

Additional Credits

Photos courtesy of New Vrindaban. Illustrations by Carson McNamara.