Author Talk: Duncan Ryūken Williams on American Sutra

[00:00:00] Natasha Heller Good afternoon everyone. I'm very pleased and honored to have the opportunity to introduce Duncan Ryūken Williams this afternoon. I've crossed paths with Duncan several times. I first encountered him as a first year Ph.D. student at Harvard, where Duncan nearing completion of his own Ph.D., had a reputation as a star graduate student. Not only was he working on his own dissertation, Duncan was also in the process of finishing a survey and analysis of the dissertations produced in Buddhist Studies which remains a valuable window into the history of our discipline and the type of study that really should be repeated. I met Duncan in Berkeley at the University of California where I had a postdoc and he was gaining a reputation as an institution builder. He continued this at the University of Southern California where he oversaw the creation of the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. And there I waved at him across the miles of eight lane traffic from my office in West L.A. Even before he completed his Ph.D., Duncan had co-edited two books, and now you understand why he was the star graduate student. The first with Mary Evelyn Tucker is Buddhism and Ecology: The Interconnection of Dharma and Deed, published by Harvard University Press, the second with Christopher S. Queen, is American Buddhism: Methods and Findings in Recent Scholarship. Both of these are pathbreaking books in Buddhist Studies, showing how scholars of Buddhism can and should participate in conversations about ecology and about American religions.

[00:01:25] Natasha Heller These two books are followed by his monograph, The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Sōtō Zen Buddhism and Tokugawa Japan, published by Princeton University Press. This work opened up new landscapes in the study of Tokugawa Buddhism. More recently Duncan has co-edited Issei Buddhism in the Americas and also edited the two-volume set, Hapa Japan which explores the global mixed-race identities of persons of Japanese descent. These two volumes are supplemented by an online resource, the Hapa Japan Project, with news stories, articles, and interviews. His most recent book is American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War. Here, Duncan brings his wealth of knowledge and research acumen to a story that had yet to be fully told, and one with important resonances for our own time. We'll be hearing part of that story today. So without further delay please join me in giving a warm welcome to Duncan Williams.

[00:02:26] Duncan Williams Thank you Natasha. That makes me sound significant or something but it's very much a pleasure of mine to join all of you here. And I appreciate the Department of Religious Studies for sponsoring this event. I wanted to maybe start today about this new book. It is about the World War II Japanese American internment or incarceration, but from a new angle, Buddhism. And I'm going to try to get into that a little bit later. But I thought maybe I'd start today by talking about grad school and back when I was a Ph.D. student at Harvard and I was working at that time with one of the really great scholars of Buddhist Studies in general, Masatoshi Nagatomi.

[00:03:24] Duncan Williams He was Harvard's first professor in that field hired in 1958. And so you can imagine I was kind of like at the very tail end of his very long and distinguished career. And this book, American Sutra, about the Japanese American internment and Buddhism, actually has everything to do with my professor and mentor. In a way it's a book, a kind of tribute to him. So this book, and I'm so glad so many people turned up, because it took me over 17 years to do and it would kind of suck if nobody came. But it's a book that began with this kind of very personal reason. I was just finishing up, as Natasha mentioned, my Ph.D. program and I was considering how to proceed in my career as a person that did the history of Japanese Buddhism. And it would never have occurred to me to do such an extended thing about, you know, something like the World War II Japanese American internment. But, right after I finished up, Professor Nagatomi passed away suddenly. And I was asked to, by his family, to perform the memorial service along with a friend of mine Mark Guneau. We co-officiated his service because in my other role I am also an ordained Buddhist priest and the family asked me to do something for his remembrance. And in that process the family also asked me. You know he passed away suddenly but he had always thought that one day he'd like to gift his amazing collection of books in Buddhism—he had everything from Sanskrit and politics to Tibetan and Chinese and Japanese—like just a massive collective that he'd like to donate to some library in the future. His office was always this kind of old school-like, office of papers, dissertation chapters, mixed with books and it's like mountains everywhere. I think he had an order to everything but it looked like a very disorderly office. So the family asked me, could you go in there and see what is good to give as a gift as a donation for a library, and what would be good to like pull out of there. They said anything written that looks personal, please pull it out because we don't want that to go.

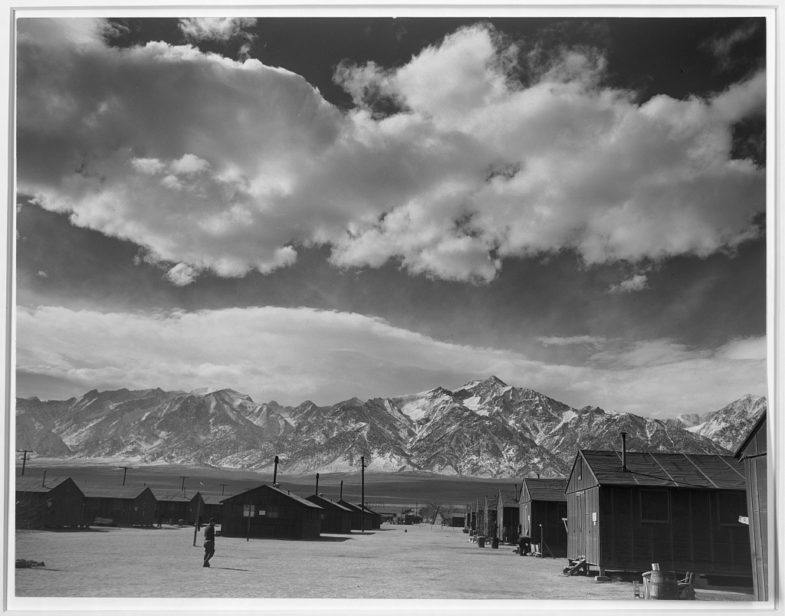

[00:06:07] Duncan Williams So I went in there and I used to do, as one of his teaching assistants, and I would take his Japanese notes—he would write things in Japanese—and then I'd have to type them up and these would be the literal notes for class. So I knew what his handwriting looked like. And there was something that had the word 'Nagatomi' in Japanese in it, but I could tell it wasn't his writing. So I pulled it out, because I thought this might be one of those personal things that I need to pull out. And I started reading it. I don't know if you can see the screen very well, but what's on the left here is one page of the document I pulled out. And it was, I would come to learn, not his writing but his father's writing. And so you can see his father to the right there, Reverend Shinjō Nagatomi, a Buddhist priest who had served before the war in San Francisco. It's called the San Francisco Buddhist Church. And after the war, in the Los Angeles area at the Gardenia Buddhist Temple. And, at the time I started reading it, and the family was like, "oh, this is you know something that's valuable for our family history. Could you translate this diary?" And so I started embarking on that and I figured out that this was written in 1942, '43, '44, behind barbed wire in a camp called Manzanar, one of the big Japanese American incarceration centers in eastern California. And to my shame I didn't really, I grew up in until I was 17, in Tokyo, Japan, and I didn't know that much about American World War II history, and the fact that you know roughly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, two thirds of whom were American citizens, had been put into these camps like Manzanar, many of them holding a little over 10,000 people each. So there were ten of these camps. So I didn't know very much and so I tried to translate some of these words that are in there like "mess hall," I was like, "what's a mess hall?" And I wasn't trained in Buddhist Studies to know that much about this kind of history. But along the way, and the reason this book took 17 some years was because I had to kind of, I kind of dedicated to it as a constant side project that I would like to not only translate this diary for the family, but also learn enough about it that I could put it, give it some kind of context.

[00:09:00] Duncan Williams And so I ended up spending about two or two and a half years in different archives in Washington D.C. at the National Archives at different kinds of Buddhist archives, until I collected thousands and thousands of pages. I began translating this diary and then other families who had, you know a Buddhist uncle or grandfather or who was also an ordained priest, they started giving me you know diaries to translate too. I translated about a dozen diaries. And then I interviewed about a hundred-twenty camp survivors, people who had lived through the World War II experience. That was the basis on which I tried to write this book, called American Sutra.

[00:09:47] Duncan Williams Now, when I first started translating this thing I would go to my now deceased professor's, my mentor's widow, his wife, and I would take her a couple pages at a time. And every time I would go, she kind of started to share some of her own personal experiences of the World War II period. She was only 10 or 11 years old at the time, and she was, unlike my professor, who was born in Japan, and a rigid Japanese national, she was Japanese American. She was born in a small Central Valley town in California called Madera, California. Her parents were from Wakayama prefecture in Japan, and she grew up there in a kind of agricultural-oriented community and and a place that had a lot of Japanese Americans doing farming.

[00:10:46] Duncan Williams And so she would slowly relate to me. I think it took like four or five visits before I got the full story, but she basically related the story of what happened to her and her family right after Pearl Harbor and the attack in December 1941. She said that the community that she lived in was on kind of like high alert, because a lot of the community leaders were getting picked up by the FBI right after the Pearl Harbor attack. And one day she comes home from school, it's like three o'clock in the afternoon, she comes home from school, and then she sees right at the door of her farmhouse her dad being beaten by some men in suits. And then she goes closer and peers inside the house and she sees her mom sitting really still at the kitchen table with somebody pointing a shotgun to her mom's head. Now she's only 10 or turning eleven, so she's quite astonished and scared at what she's seeing. But she realizes very quickly that she needs to approach this situation, because, her parents being from Wakayama prefecture, they didn't speak almost, they didn't speak very much English, and clearly these men in suits didn't speak any Japanese. And so, she would come to be the translator in this situation and soon it became apparent that these men in suits were agents from the FBI. And that they had come, they told her, that because her dad was on a list like a national threat security list because of his leadership at the local Buddhist temple. And that she was trying to explain to the agents that her dad, you know unbeknownst to him, he didn't know these agents were coming, so he was apparently out in the lettuce fields and there's some rabbits or something and he wanted to scare them away so he had a shotgun and he's kind like firing it to kind of scare the rabbits away. But that's unfortunately the precise moment when the FBI cars rolled into the farm. So there's like a lot of confusion, and so she had to kind of clarify for them what was going on.

[00:13:02] Duncan Williams Now, she mentioned that after this incident, they basically told her dad, look, we'll just come back a different day. And you're not a Buddhist priest, you're a lay leader of the temple, so we're not gonna pick you up today. We're gonna come back for further questioning tomorrow, or a different day, and they would actually come back several times. But her dad was—after the agents left—he was talking to his wife and his 10-year-old daughter. We have to prove our loyalty. We're not dangerous just because we're Buddhist. We're not a threat to national security. We're not spies or we're not engaging in sabotage. We're Buddhists, but that doesn't mean that we're a threat.

[00:13:53] Duncan Williams So what he did was he went and scoured the house and found anything he could find that had Japanese kanji or characters on it, and either had "Made in Japan" on it. And for her as a 10-year-old girl the worst thing was he collected her, it's called Hinamatsuri Ningyo, these girls day dolls, and then just threw all of these items into a fire. At that time Japanese-style bathtubs were fired by wood fire. It was one of this girl's chores to build the fire for the bath so she was doing that, but she horrified that her dad was well, mainly horrified that the dolls were going in there. And so that's what she related to me. And she said then her dad hesitated. He had this one last set of things he was going to throw into the fire but that he decided not to. And she'd asked him like what could be more important than my dolls? And he explained to her that, that, he had a sutra looked like a pure land sutra that had been handed down in his family, and that he didn't feel it was right to put that in the fire. He also, as the head lay leader at the local Buddhist temple, had all the minutes of the board from the founding of the temple all the way up to December, '41, and so he felt like this was not something that he could just throw into the fire. And so he asked his wife to get a rice cracker box and some other old kimono to wrap these documents in, then got the backhoe out, went near the large tree next to the garage, and dug a hole there and buried this box with a Buddhist sutra or a scripture in it, and this history of American Buddhism of his temple in California.

[00:15:59] Duncan Williams He buried that. I'm going to come back to the story at the very end. But, what I wanted to note, when she told me this story, was that this was a family that knew that Japan and United States was at war, and the loyalty was going to be questioned. And they wanted to assert that they were upstanding residents and citizens of America. But, that their Buddhism was not something that they could so easily erase. So they could burn away anything that that linked them to Japan in a certain way, but they refused to burn away their faith. And that was one family's effort I think to make a claim. That one could be both Buddhist and belong in America at the same time.

[00:17:01] Duncan Williams And so a lot of what my book does, American Sutra, it's a collection of those types of stories. Stories of those sorts of people, who both right before going into camp, during camp, and thereafter, found ways to make that kind of claim—that you can be both Buddhist and American at the same time.

[00:17:22] Duncan Williams Well no, I was going to do this as a quiz session, so I shouldn't show this thing. Natasha mentioned UC Berkeley. I'm just going to ask as a kind of pop quiz. I hope most people have heard of the University, but it's also the name of the town. Does anybody know why Berkeley is called Berkeley?

[00:17:49] Audience Member English poet.

[00:17:50] Duncan Williams Yes. Poet, philosopher, Anglican Bishop—George Berkeley. He was well known to have written this poem, called "America." And apparently, the trustees, the regents of what would come to be known as the University of California, the first of the ten campuses that we know today, first, they had a college in Oakland and then they were standing on what's called the founder's rock looking over to the Golden Gate, which you know today is the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, beyond which is the Pacific. Of course, there's no bridge at that time. But in 1860 they built this new university. But apparently, they were trying to figure out what to call it. And one of the trustees recalled this poem, called “America” by George Berkeley. And I just want to read one stanza of it.

Westward the Course of Empire takes its way.

The four first acts already past,

A fifth shall close the drama with the day:

Time's noblest offspring is the last.

There are other verses. But this idea, that of manifest destiny, of America as a land that is narrated as a history going westward, that pioneers trailblazed. You know there's a reason why the Portland Trail Blazers are called the Portland Trailblazers, like Lewis and Clark. Like this idea that the American story is a story that's about westward expansion. It's about bringing, as George Berkeley kind of suggests, this kind of England becomes like New England, right? And a European civilization, including Christianity, moves and goes into territories, that are at least in that point of view, devoid of civilization, even religion. And so, the expansion of America westward is this kind of thing, that apparently this trustee recalled when he was looking even further westward across the Pacific from where the university would be built. I mention this because my book opens with a series of poems by, not an Anglican bishop, but a Buddhist priest, a Rinzai Zen Buddhist priest, called Nyogen Senzaki. And he is writing a poem about this period in the spring of 1942 when he is about to be taken. He's been forcibly removed from his home, and he's about to be taken to one of these—I mentioned Manzanar—one of the ten big war relocation, WRA camps. There's another one in Wyoming called Heart Mountain. He's about to be taken there and he writes this this poem (entitled “Leaving Santa Anita”):

This morning, the winding train, like a big black snake

Takes us as far as Wyoming.

The current of Buddhist thought always runs eastward.

This policy may support the tendency of the teaching.

Who knows?"

It's an interesting poem, right? This phrase, the current of Buddhist thought, kind of, running eastward, bukkyō tōzen, Buddhism and eastward advance or something like that. It's based on, you know Nihon Shoki and then, Nihon ryōiki later. There are these classical Japanese historical texts that talk about the kind of eastward movement of Buddhism. That it begins in India, but it goes through China and Korea and finally lands in Japan. That kind of idea—on the eastern edge of Asia. But this Buddhist priest, is talking about going from California forcibly. When he says "this policy," he means the U.S. Army's policy of removing Japanese Americans from their homes on the west coast and moving them inland. And he's saying he may support the tendency of the teachings. Who knows? In other words, the reason I wanted to kind of do this George Berkely poem and this poem, is that it's about two different visions of America. Right? Because for Asian people, who have emigrated to America over 160-170 years, their American story is not about going westward. Their American story is about going to Hawaii, landing in California, and Seattle, and moving ever eastward. And in this case, Senzaki is saying, it's not just Asian bodies that are moving over, but Asian religions that are moving eastward. So, I wanted to just put that out there as a kind of placeholder for something I'm going to come back to a couple different times in the talk—about what this book is all about, which ultimately, it's about what is America. And, what does it mean to have multiple migrations from different directions that constitute something called America.

[00:23:40] Duncan Williams But let me go back to what happened with my professor's wife's family. The reason they were so concerned right after Pearl Harbor was because they had heard the reports about what happened, even on Pearl Harbor Day. So, most people know in December 1941, that attack happened on a Sunday. And in Honolulu, Buddhist priests were as usual, on Sunday mornings, they were doing services. And so they hear of the attacks. One of the people that is killed is a devout Buddhist member of the U.S. military. He's serving in the U.S. Army. A Japanese American person. And they start getting these reports about, not only people dying from the attack, including Japanese Americans. But also, that leaders in the Buddhist Japanese American community were being picked up. And the very first person picked up at 3 p.m. that day, even before the smoke had cleared, was Gikyō Kuchiba, the head Buddhist priest at the Honpa Hongwanji Buddhist temple in Honolulu. It's the largest temple in Honolulu even today. And so he was picked up. Second person picked up a Soto Zen priest at Taiheiji Temple. Third person picked up, another Buddhist priest. You'd think maybe the FBI would go after consular officials, you know, but they're going after Buddhist priests. Immediately. And what that indicated was that Buddhist priests were as a category of person, categorized by the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Army G-2, and the FBI, as a category of person within the Japanese American community, who would be considered the highest level of national security threat to the United States. They had a list called "the ABC list" in order of danger I guess. Threat to national security, and "A" was the most dangerous. And so Buddhist priests were in this category of leaders, that if in case of war with Japan, were to be picked up. Now, you know sometimes scholars in the past used to say it was war hysteria that internment happened or massacre. But it couldn't really have been war hysteria. I mean, it could've been a part of the calculus later. But, within hours of the attack, people were getting picked up. So what does that mean? It means that lists and gradations of lists had already been put together prior to the war. And in my research, what I found out and I talk about in the book, is that as far back as 1937, 1938, 1939, all three Army, Navy, and FBI had begun to make lists of people. Had begun to put Buddhist temples under surveillance, all in anticipation that war with Japan would happen. Pearl Harbor was a surprise because all the intelligence agencies thought the Japanese Imperial Navy would attack Manila, and not Pearl Harbor. But the idea that one needed to be prepared, in terms of going to war with Japan, had been in the making for quite a few years before the so-called surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. And that once war in Japan was declared very swiftly 3:30 p.m. So although Bishop Kuchiba was picked up at 3 p.m., thirty minutes later, martial law was declared. Civilian government removed, territory government removed, and a military government in place in Hawaii. And they knew how to close down Japanese radio stations, press, pickup people etc. So, this is not something that came out of the blue, the first part of the Japanese internment.

[00:28:02] Duncan Williams But I think possibly better known is what happens after February of 1942. So not the first people arrested, but what happens in February of '42 is President Roosevelt on the 19th of February issues an Executive Order 9066. It says and establishes a Western defense command zone on the West Coast of the United States, and says anybody living there is now subject to the Army's determination about who constitutes a threat to national security. And, as I mentioned roughly 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, two thirds of whom are American citizens, but over two thirds of whom are Buddhist, get deemed by the U.S. Army as a threat to national security subject to forced removal. And so people are given, usually they had between a week and 10 days. So if you can imagine if you're a student here, or if you were a student at a college in Washington state, Oregon state, or California, you get a notice you have one week, seven days maybe ten days, to report to civil control station to be taken to some camp. You don't know where you're going. And it's indefinite. They don't give you a timeline like you have to go to camp for like two years or three. You just have to go. And they tell you, you can only take what you can carry. So that's for most people, meaning a suitcase. Right? So you have to kind of go to apartment, house, and figure out what are you gonna take, and what can you possibly sell or store. That's what most people faced in the spring of 1942 after that executive order came out. And this time it was not about Buddhist priests or leaders and levels of threat. Everybody went. By everybody, I mean for example, Colonel Karl Bendetsen, one of the chief architects of this entire forced removal project, he said, he was at an orphanage in Los Angeles, it was an orphanage that held a lot of these Asian and especially Japanese children without parents, or mixed-race Japanese children. And the director of the orphanage asked him, are these babies or 3-year-olds or 5-year-olds, are they also subject to executive order 9066? Are they also to be considered a threat to national security? And he said, "if they have a single drop of Japanese blood in them I want them in camp." That's his quote. So that was a totalistic removal of an entire community. It didn't matter if you were a baby or an infirm grandmother, you were going to go to camp. All right. So that's what happened.

[00:31:07] Duncan Williams And in his 1943 final report, Lt. General John deWitt, the head of the Fourth Army, the person controlling the Western defense command zone, wrote a report in which he justified the forced removal of all these people. Saying that, and this is in his words, "It's because of their customs, traditions, race, and religion." All right. So in other words, the fact that this community was majority Buddhist, was a factor in the thinking of these officials—that these people can't be trusted. Just like my professor's wife's family also felt that when the FBI came to visit them. The fact that they were Buddhist seemed to be playing into why they seemed to be considered a threat or disloyal to America. So they went to places initially like this. This is a few miles south of Seattle, Puyallup Assembly Center. They euphemistically called these places assembly centers—former fairgrounds, former racetracks. And one of the first indications about how they would need to consider themselves when they first went into these camps, was that they had to go through a process where they look through your suitcase to make sure you didn't have any contraband. And the Army policy said that if you have anything written in Japanese, like in terms of a book, a published text, like it could be a Buddhist scripture, it could be even like a book of poetry or something—that was considered subversive, dangerous, and contraband to be confiscated from you. The only two exceptions was if you had an English Japanese dictionary, that was ok. And the other exception was if you had a Christian Bible, but translated into Japanese, that was ok. So one of the things I talk about in the book a lot is this idea of Anglo Protestant normativity. But this idea that Anglo, both in sense of whiteness, but also in the sense of kind of English only. But that there was a kind of understood norm of what it meant to be a kind of loyal American. And so, the idea was that if you can't racially assimilate into whiteness, at least become Christian, you know. That was a kind of bar that was set for them. And so Buddhists felt this clear message from the government that they didn't belong. That they weren't a part of what could be even conceived of as American. But take a look at this photo. This is at the livestock expo center in Portland Oregon. And here you see this family clearly prepared because they had sheets and they brought with them what they could in their suitcase. This was the family of Reverend Tansai Terakawa, who was the head of a temple in Portland called the Oregon Buddhist Church. And that's his daughter, Hiroko Terakawa, playing checkers with her friend Lilian Hayashi, inside one of these, what were not many few weeks ago, a horse stall. And they had tried to beautify it. Tried to make it a place that was dignified. But also if you notice there's a Buddha photo hung on the wall next to a large American flag. So for this family even if the Army had this contraband policy, even if they were told you don't belong, they claimed a place in America by saying we can be both Buddhist and American at the same time.

[00:35:11] Duncan Williams I'm not keeping track of time. Where are we at? Ok, I'm going to try to move through this quickly. So one of the things that people did once they got to camp, was if you can imagine if you've lost everything in terms of your business or your life's been disrupted, you're out of college or you have worked so hard in the years before the war, and you don't know what's going to happen to you, how long you're going to be in these places that were often in the remote interiors in desert-like environments—very hot during the day, very cold at night, these tarpaper barracks built very hastily with holes in them. So it's just a harsh environment to live in. People were feeling dislocated. People were feeling loss and uncertainty. And in that time the idea of somehow recreating normalcy, recreating life, recreating something that would give meaning and direction. People unsurprisingly turn to their faith. If you are a Christian, to their Christian faith. If they're Buddhists, and because a majority of that community was Buddhist, they turned to their Buddhist faith. And so, they try to recreate Buddhism in camp. And one of the things that I found really surprising, moving, about what these people did, was they took whatever they could to make that Buddhist life possible. Like one of the first big rituals in the Buddhist calendar in the Japanese traditions is called Hanamatsuri. It's usually held in April, as literally flower festival, it's the Buddha's birthday ceremony. And it's called that because, according to legend when the Buddha was born the heavens are so happy that it rained sweet rain and flowers. And so you have this little altar with flowers on it, you have a little baby Buddha, and the ritual practice of the members of a Buddhist community is to pour, on the Buddha' birthday, the sweet tea over the baby Buddha statue. But they didn't have sweet tea. They didn't have flowers. And they didn't have a statue. So, what did they do? They did have Army rationed sugar and coffee. So, they made a sweet coffee drink. They had toilet paper and beets in the mess hall. They would dye the toilet paper and make origami out of toilet paper, like flowers. In one camp, one of the young Buddhist men that knew how to carve things went to the mess hall, found the largest carrot that he could find, and carved a Buddha statue out of the carrot. And poured that sweet coffee on the carrot Buddha. In this slide you see other people. The Nishiura family where well-known carpenters in the San Jose area. They built the San Jose Buddhist temple. They were in Heart Mountain like Nyogen Senzaki. And they built a beautiful altar—they're master craftsman—out of desert wood, scrap wood, whatever they could find. In those days fruit and vegetables were carried in wooden cartons. And so they would use scrap wood to make an altar, make something that would allow them to practice their Buddhism.

[00:38:46] Duncan Williams The other thing you see here are oranges. They had a ration of one piece of fruit per week in certain camps. So peach pits. One of the people gathered these peach pits to make that which they didn't bring in that suitcase. And so it was that ultimately, these people were able to practice their faith in camp. I sometimes call it the tri-faith, but it's Buddhist, Protestant, and Catholic. The civilian agency that took over after the Army for these big camps of War Relocation Authority, they ultimately recognized that President Roosevelt had engaged the war with fascist Italy and Nazi Germany and militarized Japan, based on this idea of the four freedoms that America was fighting as a democratic country for these four freedoms. One of which was religious freedom. So it seemed too, as you say, problematic to deny these people, that they forcibly put in these camps, their religious tradition even though Buddhism was not a preferred religion for the government. They recognized that the majority of people belong to that tradition, so they allowed three different buildings where they would practice Buddhism, various forms of Protestant Christianity, and various forms of Catholicism. And one of the things that those barrack churches did in the very early years of camp was to provide a space for funerals and memorial services. I mentioned that some of these camps were built very hastily, that the tarpaper barracks were not very well built. And so, in the extreme heat and the cold at night, those who were vulnerable—the very old, babies, that first winter many, many, members of the community passed away. And they held, you can see this is a funeral for a baby in one of the camps, Minidoka, Idaho. But that kind of ceremony took place with much frequency that first winter of '42 and spring of '43.

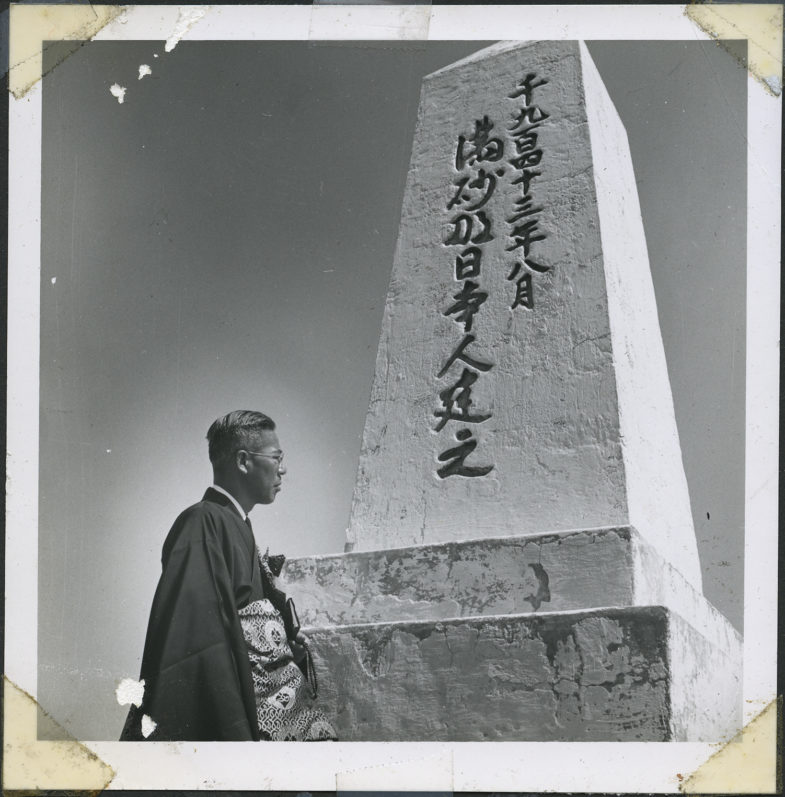

[00:41:03] Duncan Williams I'm going to circle back to my professor's father, Reverend Nagatomi. One of the camps I mentioned, that diary that launched me into this project. He wrote about the making of this monument in 1943. In the Japanese Buddhist tradition is something called Obon. It's like a summer festival or set of rituals and festival where people remember and celebrate the return of ancestors for a short period of time. And they celebrate by having Buddhist rituals, but also, these kind of dances, they call Obon dancing. And so, this photo—it's hard to read the Japanese—this says “Manzanar Bukkyokai Bon Odori, 1943, August the 15th.” And you can see, a lot of people in this large circle participating in this Obon dance. But the day before is when he's standing in front of this monument built out of concrete. Now he had performed so many, he writes about it in his diaries, so many funerals. And in the Buddhist tradition, in Japanese way, they have this idea called Hatsu Bon or Nii-Bon, this kind of first Obon after somebody dies is a particularly important one to recognize that person's passing. And so August 15th or mid-August is usually when all this is held. He's desperately going around barrack to barrack asking each family to donate five cents, maybe 10 cents per family, to build some kind of monument. Something where they could build something around a cemetery for all of these people who had died and recognize them and not let them be forgotten. And so he called it the Ireitō. Tō means like a tower or monument. And I-Rei, to honor the spirits of those who passed away recently, but even the spirits of the ancestors of people come before. And he practiced, he writes in his diary, writing those three characters so many times because, once you put it on concrete you can't mess with it. So he practiced that so many times. That monument, if you go to Manzanar today, it's run by the National Park Service. It's become a national monument. But that monument's still there as a kind of feature. It represents all of the ten camps. It's one of these iconic monuments that was built in the camp days that's still there.

[00:43:52] Duncan Williams Ok. I'm going to, just for time's sake try to wrap this up. I started today with that poem by Nyogen Senzaki. Here is a little sketch of him by Estelle Ishigo. She was a Caucasian woman whose husband was Japanese and she went into this camp with him, the one in Wyoming, called Heart Mountain. She was constantly sketching things, goings on in the camp. One of the things she sketched, she writes, a monk teaching Buddhism. It's Nyogen Senzaki. I mentioned this idea of the eastward movement of Buddhism. He actually called his little barrack “Tozen Zenkutsu.” Kind of like the Zen meditation hall of the eastward transmission or eastward movement. And he called it the Wyoming Zen-do, the Wyoming Zen kind of practice place. And so, he would teach Buddhism in camp, and he would frame their experience of being in camp through Buddhism. Now at the very end I promise to come back to Mrs. Nagatomi, you know, the 10-year-old girl in Madera, California. I want to come back to that story. They learn like most Japanese Americans, right around 1945, that the war is going America's way and that the government is starting to release people from camp as long as they move east of the Rocky Mountains. But also, they're planning to return back to the Pacific Coast, and of course once the war ends most Japanese Americans ended up going back to the Pacific Coast to their former homes. They tried to return to Madera, California. And at the time, like many other Japanese Americans when they were told to go to camp, they're desperate. Right? You have to sell your grocery store or in this case farm. They sold it for one twentieth of the market value when they first left. But when they returned, they had hoped that the people that they had sold it to would let them buy back at what they had sold it for. But the new owner said, no, you're going to have to pay market price. And, of course, during the war they hadn't had the means to have money to buy that kind of price property back. And so, they had relatives in L.A. so they thought, ok, we're going to end up there. But the dad was like, I got to find that box that we wrapped that Buddhist sutra and the family history. We've got to find that box again. But unfortunately, during the war the new owners had also cut down all the large trees and torn down the garage. He never found the box.

[00:47:03] Duncan Williams So somewhere in the soil of California is kind of Buddhist history and Buddhist teaching is kind of buried. And, I wanted to end with this thought that the project of the book is to retrieve those teachings so that history, those memories, that have been in some sense also buried in people's minds. But I also wanted to end with this poem about why I ended up calling the book American Sutra.

[00:47:37] Duncan Williams This is a poem that Senzaki first writes when he learns that he's about to be forcibly removed. And so, on May 7, 1942, he writes this poem called "Parting." And he writes it to his Buddhist sangha or group in Los Angeles. It was a multi-ethnic sangha that had Latino members, white members. But of course, all the Japanese members had to go to camp. But he's writing to the community that's left there. And he says:

Thus have I heard:

The Army ordered

All Japanese faces to be evacuated

From the city of Los Angeles.

This homeless Monk has nothing but a Japanese face. He stayed

here thirteen springs

Meditating with all faces

From all parts of the world,

And studied the teaching of Buddha with them. Wherever he goes,

he may form other groups Inviting friends of all faces,

Beckoning them with the empty hands of Zen.

So, that first line, thus have I heard, the Buddhist studies scholars will all know, it's the classical line preamble to a Buddhist sutra or a Buddhist scripture. After the Buddha died, you know things hadn't been written down, so they had this assembly where one of the monks known for being very good with their memory was asked to kind of recite all of the teachings of the Buddha, and he prefaced it with "thus have I heard". And I mentioned earlier about the eastward movement thing—seems like he always does slightly odd things. And so, he decides, ok, I'm about to enter some internment camp, but "thus have I heard." He writes a poem where the teachings that might properly come from the Buddhist canon, in the lines that follow "thus have I heard," is replaced by lived experience. His experience. The experience of those yearning for a place for Buddhism in America. He's saying I may have a Japanese face, but I'm here because I want to create a community that is of all faces. And so that was his aspiration. And to me in that sense there's a teaching in the lived experiences of what happened to the Japanese American Buddhist community. They are a community who are told you don't belong. They are a community who are told you don't deserve due process or religious freedom. But they were also a community that said due process, equality under the law, religious freedom—these constitutional ideals of America are just words on a piece of paper unless you embody them, you actualize them, and live them. And so that's why I called the book American Sutra because I think there's a teaching in that, in that process of families like the Kimora family, my professor's wife's family, who said you know what, I think we can be both Buddhist and American at the same time. Thank you. Applause.

[00:51:08] Duncan Williams I'm happy to take questions.

[00:51:38] audience member question What kind of archive exists of the material culture of the Japanese American camps?

[00:51:38] Duncan Williams Both at the sites themselves. Minidoka, Idaho. Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Manzanar, California are the best examples. Some of the other camps are like the ones in Arkansas. I went there. They're just cotton fields. There's an old cemetery for those who died and that hasn't been disturbed but, there's been no recognition by the National Park Service to create an interpretive center in the way that Manzanar, Heart Mountain, and just this past July, Minidoka, Idaho is now part of the National Park System. So the sites themselves and institutions, for example in Los Angeles, the Japanese American National Museum has a great collection of some of this material because otherwise it's like ephemera. It could easily have just been forgotten. Right? So collecting diaries, photographs, material things made in camp and so forth. These are certainly collected by that National Museum, as well as a smaller museum. The Smithsonian has a small section now at its National Museum of American history. Wing Luke Museum in Seattle. The Nikeii Legacy Center in Portland. So different cities have different places that either acquire this kind of historical material from an Asian American point of view or from in the case of the Smithsonian an interest that this is actually part of American history more broadly.

[00:53:19] audience member question So you mentioned that among the incarcerated majority of them were Buddhists, but there were some Christians as well. How did that work for the interactions between the two groups? Were they officially in these camps together?

[00:53:30] Duncan Williams Great question. So in the book I talk a little bit about both tensions and cooperation. So sometimes if you can imagine, there were these tensions sometimes within the Japanese American community about whether to cooperate with the American authorities or whether to protest. And Buddhists tended to be on the protest side of things and Christians tended to be on the cooperate side of things. And so sometimes it had less to do with religion per say, but just that divide of like, I think most Japanese American Christians probably had more co-religionists fellow religionists of other faiths back then. I mentioned Senzaki had a multi-ethnic temple, Buddhist temple, but not all Buddhist temples were like that sometimes were really just a hundred percent you know kind of ethnic temples. Christians tended to have a little bit more of that sideways cross-ethnic connection. But that said, there were certainly you know if you think about the Supreme Court cases like Korematsu, they're all Quaker you know like, Hirabayashi was a Quaker. There were also Christians that also protested what the government was doing. And so sometimes that was a tension. But just to give you an example of the interfaith cooperation that monument I showed at Manzanar today, Reverend Shinjo Nagatomi told me he knew that even though he did a majority of all those funerals for the people, he knew that some of those babies and some of those elderly grandmothers and grandfathers were Christian. And that he had friends in the Protestant community, especially pastors who were in the Japanese Methodist Presbyterian and Baptist churches also Holiness Church of the Salvation Army people as well. But he knew them. And so one of the things he did was, he said look this really has to be an interfaith monument for all of those who died. Yes, it's going to be placed in the context of this Buddhist summer ancestral thing called Obon. But, the design of it was done by Ryozo Kado, a Catholic architect who built several Japanese Catholic churches in the southern California area. And when they dedicated it that day when they were out there trying to dedicate it, he asked one of the Protestant ministers to come and co-dedicate it with him. So the legacy of that continues today every year in April is the annual Manzanar pilgrimage. People go, and I was there this past one too, I gave a talk there. I think a 1,500 people went in April. And always, I mean there's a program, I want there to speak, but the most solemn part of it is the interfaith service that takes place there, Buddhist and Christian.

[00:56:53] audience member question Were there any non-Japanese Budddhists interned?

[00:56:53] Duncan Williams So in terms of those who were inside camp, I mentioned that person who did the sketch, most people who were not Japanese who were in camp, there's about between 300 and 400 families that were multiracial. Where if the kids were of a certain age, you know usually as a Japanese man and a Mexican, or Caucasian, or Black woman, that pairing was most common. And if the kids were young they went in together as a family. If the kids were already older sometimes the non-Japanese parent didn't go in, ok, so that's one thing. Just to give you an answer on the kind of non-Japanese Americans who are in camp. Buddhists who were, let's say Reverend Julius Goldwater in Los Angeles, Reverend Sunya Pratt up in Tacoma and Seattle Buddhist temple. They were not Japanese so they were not subject to Executive Order 9066. So they didn't obviously need to go into camp. But, they made tremendous efforts to both deal with helping the community store everything, safeguard the temples, made dozens of round trips to these camps to take people you know they left something in that rush to get to camp. They had hoped to take something from, they would be so helpful to the Japanese Americans. And several Christian ministers, Reverend Emory Andrews up in Seattle Baptist Church, Father Tivisal the Catholic priest at the Japanese members of the Catholic tradition in Seattle. They were also making trips as well, so I guess none of these priests lived inside camp, but both Christian and Buddhist leaders who were not Japanese—and of course with the Buddhists far fewer of them—but they were very helpful and many of them ultimately like set up in the town right outside the barbed wire. They set up a base from which to be helpful.

[00:59:32] audience member question Can you talk about how your work has impacted Japanese Americans today?

[00:59:41] Duncan Williams I don't know exactly how it's impacted. You know how much time do I have?

[00:59:51] Natasha Heller We have the room for another half an hour.

[00:59:54] Duncan Williams I'll try to answer your question but in a little bit different way. If I may, I'd like to show you a photo. This is one of those, you never know how your book is going to be received or taken. And so I don't know if you can see, that somebody made color photocopies of the front cover of my book and then folded, like in origami style, some cranes. All right. This is one example of a Japanese American person who unbeknownst to me decided to fold some cranes out of the cover of my book because somehow it related to something she was doing, which was organizing a protest in Dilley, Texas. And Dilley, Texas is the site of a facility called the South Texas Family Residential Center. It's about 2,700, mainly children, separated from their families, but also some women who have been part of these Central American migrants coming up from the southern border into the United States seeking refuge and asylum. And these kids have been, you know, a part of the kind of zero tolerance policy and the administration's efforts to kind of deter caravans and immigration. So these kids have been separated from their families. And so this one group called Tsuru for Solidarity—Tsuru in Japanese means cranes—so they decided that they would, because the site in Dilley, Texas was very close to a Japanese American World War II internment camp, called Crystal City, one of the smaller camps that's not as well known. But some of them, old members who were kids back then, they were like, we were kids back when we were put behind barbed wire and detained without you know due process. These kids are trying to seek asylum. Their families are trying to seek asylum. They're not being given due process either. And now they're being separated from their families. And for these, you know they're like 85-90 years old, these Japanese American camp survivors, they're like we need to stand up for these kids. And so, on the fence at Dilley, Texas, on the left side of the slide, you can see there's fencing there, and these American Sutra cranes were a part of this crane making project. In Japanese tradition, around Hiroshima, there's like the making of a 1,000 cranes to make a prayer or wish for a better, more peaceful, more just future. They were thinking of that kind of practice when they went to Dilley, Texas. This small group, it's like 15 people, put a call out to all these Japanese American groups, and said we want to make cranes and we want to show these kids that somebody, like back then in World War II, nobody, I mentioned a few priests that helped out, but there was no politician, there was no newspaper editorials, there were nobody who stood up for Japanese Americans back then, so we're going to stand up for these people. They're so old. They're like 80 now. But they're like furiously making cranes. And they asked other people to do it. And and they made they made a call for 10,000 cranes; 25,000 cranes poured in, including someone in San Francisco. They made cranes out of the American Sutra cover. So I was like, I better get involved. And so after that I went to, that was back in March, and then in June, the Trump administration announced that they were gonna move 1,400 of these kids to a facility at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, which is today a U.S. Army base, but back then World War II, was also an RV. It's where Geronimo is buried and it's kind of like the Apache people were forcibly removed there and boarding school. There is a long history at Fort Sill, but during World War II it was again, slightly lesser known only 700 Japanese were there during World War II. But 90 of them. Fort Sill was an internment camp that had held 90 Buddhist priests. So I felt compelled like once the administration announced they're going to move some kids directly into a former space that was an internment camp, I felt moved to participate. So you can see me I'm in my robes there, part of the protests there, and again these 80-some-year olds almost 90-year-olds were also part of that thing.

[01:05:24] Duncan Williams And then there was a second version of it where I did the organizing. I put a call out to Buddhist communities around the country saying I want to ask all of you to support this thing. We had 90 Buddhist priests in this location back in World War II. And we also had three people who died in that place and people had forgotten these people. And two of them were killed by guards, near the fence. So I was like, I want to organize a Buddhist service, but also protest at that fence so that, that doesn't repeat, so that we also are praying for the migrant kids, as well as the guards that will be guarding them, so that they don't shoot or otherwise mistreat these young children. And so I put a call out. I got 5,000 cranes. In a period of about two and a half weeks and I went. And then about twenty five Buddhist priests joined me. I just said buy a ticket. Come out to Fort Sill and then 25 people did that. And so we marched with a group of people that primarily were Latinx dreamers. I mean for them it was personal. It was their cousins. And so it was this very odd kind of conflation of a Japanese American group Tsuru for Solidarity making cranes, you know this Buddhist kind of group that was now multiethnic, not just Japanese American temples participated. They were like junior high school and high school students, and they came in all across Oklahoma, Texas, whatever, to be at Fort Sill, and we did this ceremony where we remembered those who died in World War II, and I invited the kids to write the names of people that they know in that process of forced removal, deportation, incarceration, to remember them in this Buddhist ritual as well.

[01:07:41] Duncan Williams So we did this kind of, a little bit odd practice. But that's one, how to say, effect, or one way in which some Japanese American people have been setting up these little book clubs at the temples, and the Japanese American community centers, and reading this book because although the Japanese American World War II experience is a fairly well researched area–lots of books, memoir. But this Buddhism part has been missing in that story. And so I think people have been kind of keen on reading about it and then seeing how that incarceration happened because of both race and religion back then. And then thinking about who are we as Americans today. Who belongs? Who's included who's excluded? You know whether it's on the southern border around race. You know it recalls like, Yellow Peril, and you know hordes of Asians invading, and the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1924, immigration leading to internment, they know that history. They also know with travel ban around majority Muslim countries that when Trump talked about you know, a complete shutdown of Muslims coming to America, that they understood how I think this particular community, understood how both race and religion had been prisms from which to denote who belongs and who is excluded. And so I think that's maybe why some of these activities are going on between Japanese Americans and other kinds of interlinked ethnic groups.

[01:09:50] Natasha Heller It seems like that might be a good note to end on, if there are no further questions. So you brought us really into the present and the way this work resonates. So thank you again for a wonderful talk.

[01:10:01] Duncan Williams Thank you.