Diane Brown Townes [00:10]: We grew up in a period where everything was swept, everybody wanted to say it was so ugly, slavery, we don't want to say we ever did have any part in that and we don't want to say that it ever existed. So if we don't say it, we don't have to teach it in the classrooms. What they won't know won't hurt them, that kind of thing. But I beg to differ: what you don't know, can be very harmful.

Elaine Rackley [00:36]: A memorial to enslaved laborers will be on display in the Fall at the University of Virginia. It is designed to honor the slaves who built the school in 1819.

Diane Brown Townes [00:48]: It was almost like a fairy tale because they left you just wondering, were there really enslaved people or not? Because the book would sometimes call them “indentured servants” and they would kind of inadvertently say “they were happy” or “they were working for families” and that kind of thing. But they didn't really come out and say they were people who were owned by somebody else.

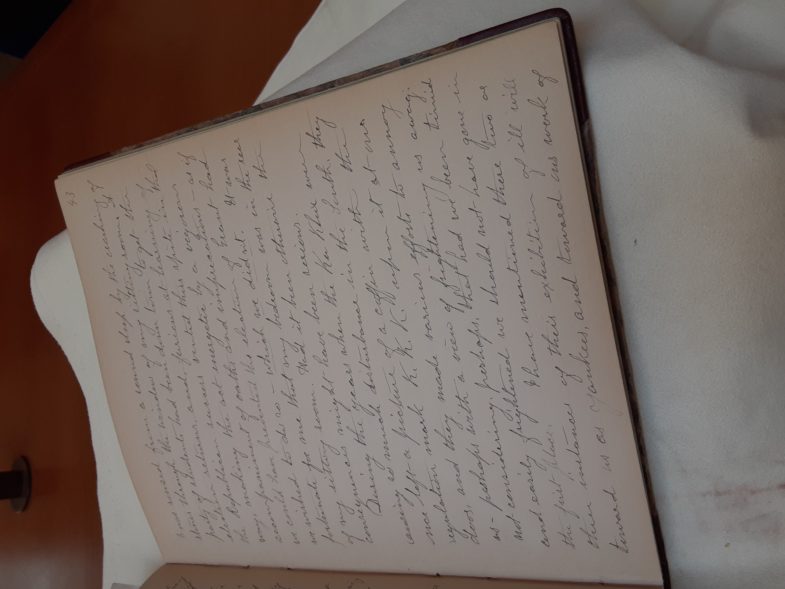

Andie Waterman-Papers of Philena Carkin [01:13]: We were too much interested in our work and too busy to let our imagination dwell upon the dark stains here and there upon the floors.

Sergio Silva [01:26]: To let our imagination dwell upon the dark stains of the past. To see. To listen to past voices and present silence. The Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia is a broken circle surrounded by a wall of gray granite that invites you in.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [01:54]: Cuando la mano de color de arcilla se convirtió en arcilla,

Sergio Silva [01:59]: For me, when I am at the memorial, a poem comes to mind. It’s more, like, fragments of a poem, like sticky lines that come and go. Something like a scattered prayer.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [02:17]: y cuando los pequeños párpados se cerraron llenos de ásperos muros, poblados de castillos,

Sergio Silva [02:24]: Words in another language, speaking of a distant world that feels, strangely, so close to this broken circle.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [02:34]: y cuando todo el hombre se enredó en su agujero, quedó la exactitud enarbolada: el alto sitio de la aurora humana: la más alta vasija que contuvo el silencio:

una vida de piedra después de tantas vidas.

Sergio Silva [02:56]: A life of stone after so many lives.

Sarita Herman [03:03]: This is the actual stone that the entire memorial will be made out of. This stone is the Virginia mist granite, it’s quarried locally in Rapidan, Virginia.

Sergio Silva [03:13]: What is the story that the stone tells? What is the stone’s voice? How does its silence sound? How does it sound when it shouts?

Diane Brown Townes [03:28]: I think overall, the overall design concept, the open ended shape evokes broken shackles and the jubilate ring shout dance in which enslaved people blended African traditions with Christian worship.

Sergio Silva [03:42]: When you enter the Memorial’s broken circle, the wall is no taller than your ankle. If you look around you still see the waving grass of the university, you still hear the noise of cars passing by, and you can see the people walking up and down nearby streets--grabbing coffee, chatting with friends, or getting a bagel. And you also hear the water.

Diane Brown Townes [04:14]: The water flows with a quiet echo from the parabolic granite wall. In addition, the water is symbolic of the brutal middle passage, but also the river's pathway to escape.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [04:26]: Miro las vestiduras y las manos, el vestigio del agua en la oquedad sonora, la pared suavizada por el tacto de un rostro que miró con mis ojos las lámparas terrestres, que aceitó con mis manos las desaparecidas maderas:

Sergio Silva [04:54]: As you keep walking the memorial’s wall starts getting taller and taller. I’d say you don’t even notice it because there’s something else that captures your attention right away: little wounds in the stone, little marks with names on them.

Diane Brown Townes [05:14]: So, the names and memory marks that honor each enslaved person.

Sergio Silva [05:17]: Warner. Mother. Abraham. Roberty. Sam. Billy. Brother. Henry.

Diane Brown Townes [05:21]: They are textured in Virginia gray mist, a granite from a quarry located in Rapidan, Virginia.

Sergio Silva [05:28]: James. Isabella Gibbons. Joshua. Stonecutter.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [05:35]: porque todo, ropaje, piel, vasijas, palabras, vino, panes, se fue, cayó a la tierra.

Sergio Silva [05:46]: Names continue to appear as the wall keeps growing, until it is 8 feet tall. Suddenly, the memorial has turned into your new horizon. The names. The lives that the stone remembers. And the stone speaks in silences. What do you hear?

Diane Brown Townes [06:12]: The past, the present and the future converging together. We have to redress what occurred during, during chattel slavery, but we also have to redress what we did to eliminate the narrative of our contributions, our people, African-Americans people's contributions to American history, that is a full bodied American history story.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [06:42]: Piedra en la piedra, el hombre, dónde estuvo?

Sergio Silva [06:48]: The stone is asking you to remember, to look back at an erased narrative. The outer face of the memorial presents the image of two huge eyes. Those are the eyes of Isabella Gibbons, and they were carved in the stone by the artist Eto Otitigbe, after the only photograph that exists of Gibbons.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [07:13]: Aire en el aire, el hombre, dónde estuvo? Tiempo en el tiempo, el hombre, dónde estuvo?

Sergio Silva [07:23]: But here is the art of this image: the eyes come and go, and you only can see them under a certain light. So, they are like an apparition, like something that isn’t always there but always comes back. Maybe it is more accurate to say that those eyes are always there, and they are looking at you even when you cannot see them.

Diane Brown Townes [07:54]: So, I started thinking about who was Isabella Gibbons? Who who was she?

Andie Waterman-Papers of Philena Carkin [08:00]: Mrs. Gibbons was a handsome, capable woman, some thirty-five years old.

Diane Brown Townes [08:04]: She served as an enslaved cook for William Barton Rogers. He was a University of Virginia professor of philosophy and she lived on campus where you see the gardens and the pavilion. And a lot of what that environment did was enabled her to learn how to read and write.

Sergio Silva [08:28]: One photograph and one letter from Isabella Gibbons are preserved. From all of a life’s words we only keep a few, published by a newspaper in 1867. Those words are carved in one of the memorial’s ends. How does their silence sound? How does it sound when they shout?

Diane Brown Townes [08:56]: We cannot forget the crack of the whip, cowhide, whipping post, the auction block, the handcuffs, the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro trader tearing the young child from its mother's breast as whelp from the lioness. Have we forgotten that by those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race have been killed? No, we have not. Nor ever will.

James Ryan [08:57]: Can we forget the crack of the whip, the cowhide, the whipping-post, the auction block, the handcuffs, the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness? Have we forgotten those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race killed? No, we have not, nor ever will.

James Ryan [09:26]: Isabella Gibbons, a former enslaved person owned by a University of Virginia faculty member, wrote these words two years after the end of the civil war. She went on to become an educator and it is fittingly her words and her eyes through which we can feel the past, reach to the stone of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, and impel us to greater understanding, empathy, and justice.

Diane Brown Townes [10:00]: She’s almost like a guardian, guardian of our stories, a protector.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [10:07]: Escuadra equinoccial, vapor de piedra. Geometría final, libro de piedra.

Sergio Silva [10:16]: A book of stone. Words in stone. Stones that are not a book. We put words on the silence. We rely on other people’s words to illuminate our experiences.

Diane Brown Townes [10:36]: The story of the memorial that, around that timeline was really related to our community. But it was also telling my personal story, my personal truth. It was telling my story. My name is Diane Brown Townes, I grew up in the city of Charlottesville, in a segregated neighborhood called 10th & Page. I lived approximately five blocks from where the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers is now located. I was enrolled in Jefferson Elementary School. I started thinking about one hundred one years after Isabella Gibbons and how my sixth-grade class came together to desegregate the Charlottesville public schools. We had not been taught anything about Isabella Gibbons.

And so I said there's one type of cruelty where you have physical, brutal, visible, external... just unacceptable treatment of human beings, but there's a more subtle and sometimes not so visible way that people are marginalized or treated less than or not even considered worthy of educating, fully educating. Those kids and people who are not yet born. They're not even here yet. I don't want them to ever have to go through not knowing how they connect with the greater community, feeling like they don't belong with in any way, have any capacity to make a difference to the community.

Naikelly Rojas-Alturas de Macchu Picchu [12:19]: Piedra en la piedra, el hombre, dónde estuvo? Aire en el aire, el hombre, dónde estuvo? Tiempo en el tiempo, el hombre, dónde estuvo?

Sergio Silva [12:36]: Stone on stone. Time on time. How do you reach those lives that are gone? Remembering is embracing the lives in the stone, the stone as something living. The past, the present and the future. The names. The lives that the stone remembers. And the stone speaks in silences. What do you hear?

Sergio Silva [13:24]: This audio piece was produced for the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab of the University of Virginia. Kelly Hardcastle-Jones is the Lab’s editor and Emily Gadek is the senior producer of the Lab. Andie Waterman voiced Philena Carkin’s quotes. Naikelly Rojas voiced the excerpts from “Alturas de Macchu Picchu”, a poem by Pablo Neruda. I want to thank Eric Höweler, from Höweler + Yoon Architecture, and Louis P. Nelson, vice provost for academic outreach at UVA, for their information on the memorial’s building process. I also want to thank Allison Bigelow, Tom Scully Discovery Chair Associate Professor of Spanish at the university, for her contributions to the project.