Equal Souls: Church and Race in Small Town, VA

[00:00:10] Eric Hilker Can you just start by introducing yourself.

[00:00:12] Gail Mann Gail Mann, I am a member of First Baptist Church Waynesboro. What else would you like to know in this introduction?

[00:00:20] Eric Hilker How long have you been a member there?

[00:00:21] Gail Mann Since 1969.

[00:00:28] Eric Hilker First Baptist churches is in the heart of Waynesboro, Virginia. It's a pretty typical mainstream mainline Protestant church.

[00:00:35] Gail Mann As it turned out, it was more important in who he became as a couple and as Christians than our wedding. My only thought was, oh, my gosh, I'm from such a small church, how can I ever be in such a big church? But I've never been sorry. And we came back to it after we moved. We were Anglicans for four years in Singapore and then came back. And so that's how long we've been here.

[00:01:04] Eric Hilker One of the things that Drew Gail and her husband to that church was the pastor, Dr. Edward Bratcher. Dr. Bratcher had been really helpful to Gail and her family during a dark time. And in this very white congregation, Dr. Bratcher was preaching about integration and civil rights from the pulpit. Gail even specifically remembers him speaking against minstrel shows that used blackface.

[00:01:28] Gail Mann Well, we never thought anything about that being something that would be… They didn't think they were being deprecating. But I guess, Dr. Bratcher felt they were.

[00:01:40] Eric Hilker So you might expect that today in 2020, on a Sunday morning at First Baptist, you'd see a mix of folks that would reflect those efforts at social change. I asked Gail if, out of the hundreds of people at First Baptist, she currently knew of any Black members.

[00:01:58] Gail Mann Um, not that I know of. It's funny thing, isn't it?

[00:02:02] Eric Hilker So why is that, do you think, do you have ideas about…

[00:02:06] Gail Mann I wish I knew. I pray about it a lot. The discussion I hear most is wishing. That we were the kind of church where they would… where there would be a more mixed group.

[00:02:32] Eric Hilker My family and I moved to Waynesboro in 2016. We liked Waynesboro. It was quiet. We felt really welcomed into our neighborhood. We still love it. But something about the Waynesboro churches stood out: in the churches we visited, there were no Black people and very few Latinx folks like my family and I, nearly everyone was white. Now, plenty of church goers listening, especially those who've lived in the South, are certainly not going to be surprised. But this is our first time living in a small town where racial separation and churches held on quite so tight, where it suddenly dawns on you, halfway through a service, whoa, are there only white people here?

[00:03:22] Eric Hilker My immediate assumption was there must be a deeply troubled history of race relations here: backlash against integration, court cases, boycott sit-ins, all the ruptures and eruptions of civil rights history, the explicit and conscious world of shifting race relations. In fact, I began researching this piece thinking I had heard of just such an instance in Waynesboro. But I was wrong. I had misunderstood.

[00:03:54] Eric Hilker Instead, Pastor C.D. Brown, who still pastors the predominantly Black church that he founded in Waynesboro 50 years ago, he tells it like this:

[00:04:05] C.D. Brown My name is Clyde Daniel Brown Junior. I'm a native of Virginia. I attended the segregated Rosenwald school. At the 10th grade, we were… we experience integration. And I graduated from Waynesboro High School in an integrated situation.

[00:04:38] Eric Hilker What was that like?

[00:04:43] C.D. Brown Um, actually, it really wasn’t a much of an experience. Waynesboro has a particular culture. Everyone in Waynesboro seemed to have found a place, and they knew their place, and they became comfortable with their place. You just sort of move with the flow, whatever, wherever the current carried you, you just sort of went that way. So the transition for me really was no… it was a void experience, really. It was really just going to a new building. And um, and dealing with a race that I had been programed how to deal with. And it wasn't like something that was preached from the pulpit, or civic activities that taught us this. Most all of us were trained in our home with our parents as to where to go, what to say. You know. You deal with them the same way that you dealt with them in segregation. In integration you deal with them the same way, so that you can just flow with the current.

[00:06:09] Eric Hilker Integration of schools was, in neighboring towns, a flashpoint of race relations. But on the stories I heard from longtime residents of Waynesboro, social patterns just sort of plodded along. The hospital desegregated. The theater desegregated. Legal segregation of neighborhoods ended. Now, the implicit social patterns of racism that currently exist in the US still exist in Waynesboro. But an African-American woman now sits on city council alongside four white males. Two out of five school board reps are African-American women. And these sorts of changes are not so much the product of great eruptions and tensions, or highly charged social movements. It's more like a slow thawing. But amid that slow thawing, the churches in Waynesboro stick out despite some really interesting moments of progress.

[00:07:05] Eric Hilker This was in the early 70s.

[00:07:09] Gail Mann The men had… they were having a revival. Baptist churches from the county, both Black and white churches, met together for prayer meetings to pray for this revival. And then at the end of that, the culmination of that was to be a communion service at First Baptist Church. Well some of the people thought that that was just too strange, but they went ahead and they did it. And our janitor at that time, I remember I remember the name is Clayburn Spears, was from a Black church. He was a deacon out in the county. And he served communion with Dr. Bratcher. And Dr. Bratcher, some people did object to the things that he proposed, but that after this service, one of the deacons came up to him with tears in his eyes and said, I will never oppose you again.

[00:08:17] Eric Hilker So here is this beautiful moment of communion between Black and white churchgoers, which break some vestiges of racist sentiment that were sitting below the surface. In some ways, it only intensifies the question: Why do churches continue to be so racially homogenous? Given these moments of progress and there've been others, why are churches not more like other institutions in town, institutions that better reflect the demographics of the community?

[00:08:49] Eric Hilker One common answer looks to church culture. Churches remain racially homogenous because they worship in different styles.

[00:08:57] (Music from First Baptist, Waynesboro)

[00:09:07] Eric Hilker And to worship authentically. People need to be able to worship within their own church culture.

[00:08:49] (Music from Christ Tabernacle, Waynesboro)

[00:09:19] Eric Hilker If you look at it this way, the racial homogeneity of churches ends up looking pretty innocent. I like to worship this way—You like to worship that way: good for you. Things aren't racist anymore. They're just different. Anyone is welcome to come to our church, worship in our way.

[00:09:39] Debra Freeman-Belle So my name is Debra M. Freeman-Belle.

[00:09:42] Eric Hilker Deborah grew up in Waynesboro during the 80s and 90s. She is the daughter of a Black preacher, involved in Black churches, but also regularly traveled to white churches for revivals where her father would preach. So she was exposed to a range of worship styles, even as a kid.

[00:10:00] Debra Freeman-Belle As a child being in a Black church, but regularly visiting other churches, opened me up to people from Pentecostal to all kinds of differences. I listen to a range of music and always say that part of it is because my dad took us to churches where bluegrass was worship, which is way different in the gospel. That exposure created some type of comfort for me, it’s not different. So I can still listen to Bluegrass now because I was exposed to it as a child and church where someone who didn't have that exposure would listen to it and be like “What in the world are you kicking your foot to?”

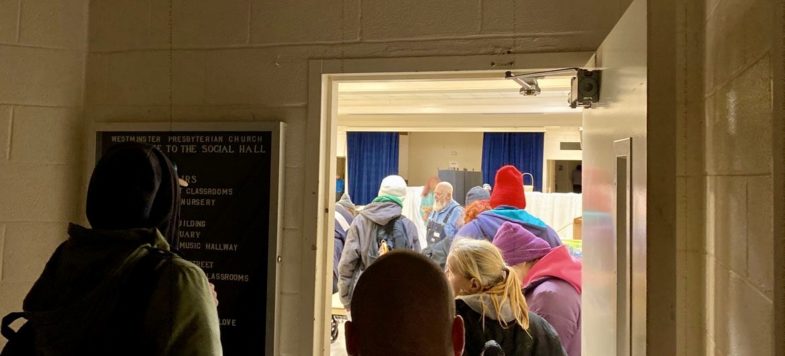

[00:10:41] Eric Hilker That ability to feel comfortable in different settings has served Deborah well. In her current job she works with more than 30 different churches in and around Waynesboro to coordinate care for homeless folks in the area. These are Black churches, white churches, mainline Protestant churches, charismatic churches, all sorts. But there was a moment when she felt a little uneasy about how white folks might judge the way she worships. And this, like many stories where Black and white people wind up worshiping together, happened at a funeral.

[00:11:16] Debra Freeman-Belle So, my grandmother passed away last year. My grandmother was a Mother in the Church of God in Christ, which is a big deal. So, very well respected. And we wanted her funeral to exemplify her life and what her focusses were. So, praise and worship, songs, hymns were very important for us to include.

[00:11:43] Debra Freeman-Belle So my board members, the majority of them, came out of respect to her funeral. Most of them had never been in what would be considered a Black service. And so I was kind of nervous, to be honest. I was like, oh, my gosh, they're gonna think of me differently because I’m gonna get up, clap my hands and dance and work through my grief with God in the way I need to. And I remember thinking before the funeral, like, they are gonna think my family is crazy. ‘Cause they have not seen anything… There's gonna be some hollerin’. There's gonna to be some shoutin’. And they're not used to that. And one of my board members, the Presbyterian deacon, came up to me outside and he's like, Debra, can I talk to you about the funeral? I was like, “yeah,” and I prepared myself for him to ask me all kinds of questions. And he said, “I've never, ever been in something like what I experienced today.” He said, “I've never stood up and clapped my hands.” He said, “I've never danced.” He said, “but I felt so drawn into it today.” And he said, “I feel like I had a spiritual encounter at your grandmother's funeral.” He said, “as if I heard an army like marching and clapping with us.” And he said “it was the most beautiful thing, and I've never been in Black gospel worship and in a service like that.” And he looked at me, he said, “I believe every white person should have to sit through a service, because there is no way you can't respond to that call.”

[00:13:09] Eric Hilker Deborah had braced herself, expecting someone to judge her because of how she worships. And this isn't how it works out in this situation. But her worry here is not without cause. She realizes that there are ways that “This is how we do it,” turns into “This is the right way to do it.” She felt this as a kid:

[00:13:37] Debra Freeman-Belle Growing up in the denomination I was in, I kind of looked at people in predominantly white churches that had way less rules and way less things that they needed to do to be able to enter heaven—I looked at them as not quite saved. That's kind of how we were taught indirectly.

[00:14:01] Eric Hilker Deborah said that this is something that's changed for her, especially as she has interacted with so many churches in the community. But she highlights a pretty common phenomenon that we often move from descriptive statements about the way things are to normative statements about the way things should be without consciously meaning to. So, “This is the way we worship,” turns into, “This is the right way to worship,” or even, “The good people worship in this way.” One of my own worries here, one of my reasons for doing this research, is the concern that, for my own little white girls sitting in an entirely white Sunday school: when they sing “Jesus Loves the Little Children”

[00:14:52] (Children Sining “Jesus Loves the Little Children”)

[00:14:58] Eric Hilker It can slide into “Jesus loves the white children a little more.”

[00:15:03] (Children Sining “Jesus Loves the Little Children”)

[00:15:08] Eric Hilker Even when the next line in the song, in racially problematic ways, explicitly contradicts that sentiment.

[00:15:19] Eric Hilker These value judgments that sit in the back of our minds, they’re the kind of judgments that are doing work when an employer is making a hiring decision; when a landlord is deciding whether to rent to a Black family; when a police officer makes a judgment on whether pull a gun; or when a neighborhood watcher decides whether a person in a hoodie is a threat to the neighborhood. In other words, these sorts of judgments are consequential to enforcing the patterns of life that keep racism alive and kicking in the US, even when people consciously say that they want racism to end. Deborah's story of her grandmother's funeral, it brings up something else, too. Even if perceptions of difference are not innocent, neither are they unchangeable. Perceptions can be altered by experiences that bring different groups together—like that communion service at First Baptist in the early 70s. These authentic moments of combined worship can change how people see each other. They can be instrumental to stopping the movement from, “This is the way we do it,” toward, “This is the right way to do it.” But these experiences are rare. And they do not seem the kind of encounters that actually change the boundaries of the groups themselves. The racial isolation of churches remains, after all, pretty frozen.

[00:16:51] C.D. Brown The general attitude is, “We're comfortable with the way things are. We don't see a need, or feel a need to do anything different. We’re not going to be ugly with you. But we just don't feel the need to do that.”

[00:17:11] Eric Hilker Do you feel differently about that?

[00:17:13] C.D. Brown About that particular disposition? Yeah, yeah, absolutely. Men and women who owned men and women have been attending church for hundreds of years, religiously and sincerely, sincere in their faith. And they never understood that you don't own a human, you know. So until we get together, we talk. We meet. We sit down. It's the only way that we are going to deal with ignorance. And I think all of this, or a great deal of this, has to do with ignorance.

[00:17:51] Debra Freeman-Belle Knowledge is power. That's all it is, whether it's in church or out of church. Hate, bigotry, or wanting to hate, hate and bigotry, all about limits and knowledge which limits our power. And so we've come powerless over something because people don't want to jump outside their box and educate themselves and have our conversations and not assume… Relationships, knowledge to me, whether in church or out of church, that's what changes lives.

[00:18:20] C.D. Brown But you…we will never be able to know a person if we don't communicate with a person. Looking at them from far will not allow me to really know you, looking at you from over there. That idea that people say “I don't see color,” that’s, uh, that's idiotic to me. You know, what's more important is that I see you as an equal human. An equal soul.

[00:18:59] Eric Hilker This desire to be known, it's significant. Not to be seen as a distant caricature, or stereotype, or an inferior member, but to really be acknowledged as an equal soul. Pastor Brown and Pastor Paul Pingel of Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church have started a pastors’ group working on racial reconciliation among churches in Waynesboro.

[00:19:28] C.D. Brown When we when we started this pastors’ group, I sort of initiated this motto: “Let’s fall in love.” If we loved if we would really pursue that type of love, I think we would find the success that we need.

[00:19:47] Eric Hilker Working toward this kind of love—it's halting, awkward, and sometimes almost comical.

[00:19:56] C.D. Brown We have been sharing social functions at different homes, you know, which was interesting. You know. You could feel the the sense of apprehension, simply because: “we don't know you.” You know. We prepared, everyone… it was a potluck and everyone prepared, you know… And even there, again, everyone was putting on a good face, but you could tell that: “I'm not sure of this particular dish. And the reason I'm not sure this particular dish, is because I don't know the people who bought this dish.” You know?

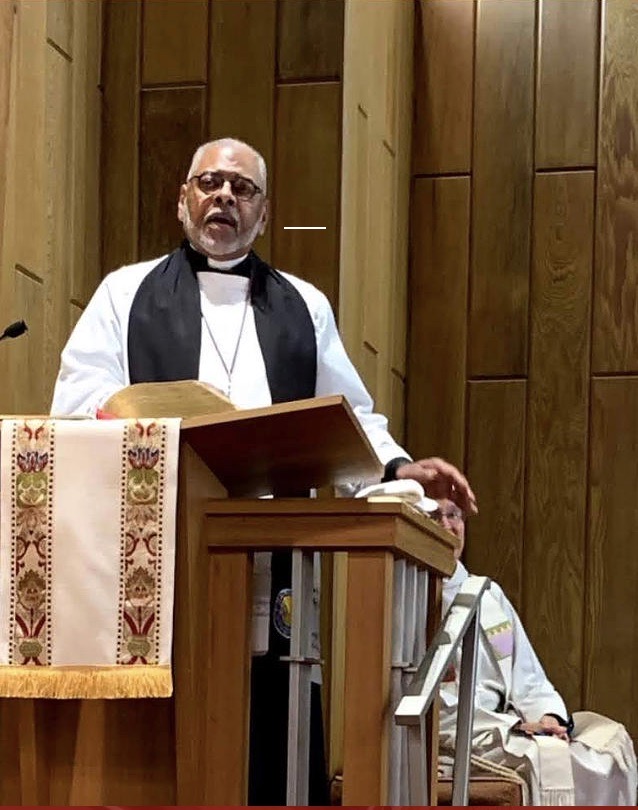

[00:20:34] Eric Hilker I saw Pastor Brown preach at Grace Lutheran, which is a pretty white church, in what's known as a pulpit swap. A couple dozen members had come with him from his own congregation.

[00:20:46] C.D. Brown They seated themselves about the second row from the front. And they were asked by some of the parishioners there, “Do you Black people always sit at the front of the church?” We laughed about it and it wasn't a big thing.

[00:21:00] Eric Hilker At the meal in the fellowship hall, after service, people mostly sat at tables with people from their own congregation. And nobody touched the cornbread I brought. I’m not bitter, but it’s damn good cornbread.

[00:21:21] Eric Hilker It's not clear what success would look like for churches in Waynesboro. Gail told me a story about a funeral worship service shared between a Black congregation and a white congregation. And in it, I think she voices the hope for racial reconciliation that's held by many white Christians.

[00:21:42] Gail Mann I mean, the unity, the unity that we have in Christ and in loving people. It was… That’s what I remember. That's what I remember. And just basking in it, because it felt like, it felt like the kingdom of God.

[00:22:02] Eric Hilker But she realizes the problem here:

[00:22:05] Gail Mann You can't expect people to come to our churches because we want to feel good, because we have all kinds of people in our church. I mean, that's just my, that's my take on it.

[00:22:17] C.D. Brown Success would look like all of us really embracing the commission of Christ. That's as simple as I can say it. I don't want you to change your reformation. I don’t want you to change your membership. Just want us to understand, really, what Christ was really trying to do. When the disciples were having difficulty with even crossing through Samaritan land, you know, or dealing with publicans, or people whose occupations were demeaning—Christ broke through all of this. That's it. When and when… Success to me is when we meet on that ground right there. I'm okay with, with a man being a Baptist, a Methodist, Presbyterian, Catholic, Pentecostal, whatever, Lutheran. I'm okay with that. As long as we have… that we have the common ground, that we on the same page when it comes to The Great Commission: what Christ really wanted.

[00:23:27] Eric Hilker After our interview, as I was getting ready to leave. Pastor Brown said to me, “You know, the elephant in the room, when we're talking about churches and race, it’s superiority. It’s the thousand small ways that people question you, that they look at you sideways when you say something like, ‘did he really just say that?’”

[00:23:51] Eric Hilker Falling in love is hard. Differences suspicious. And when the status quo favors you, it's easy to slide into the assumption that your way must be best. And others are inferior. This is not the kind of issue that one podcast can wrap up with a neat bow. The interplay of race and religion—it’s so big, so complex, so unwieldy. You can feel impossible even to get started. But you eat an elephant one bite at a time. And maybe a small story about a small town, maybe it can give us something to chew on. The continuing racial isolation between churches in Waynesboro: it’s disappointing. But unlike despair, disappointment always contains some measure of hope.

[00:24:51] C.D. Brown One of the things about the monthly meetings, I don't feel any close mindedness. You know. And I really like that. We are open to hear and to even dare to, to take each other's pulse about certain issues. To me, that's a major, that's a major movement: that you really start to feel my pulse. You're feeling my, you're feeling my heart. Of course, I'm speaking figuratively. But you're feeling my heart, and they are open and we discussed and we share, you know. And you you realize that you're really having a dialog.

[00:25:47] Eric Hilker I want to end by saying thanks to C.D. Brown, Gail Mann and Debra Freeman-Belle, for their time and really candid thoughtfulness. Thanks to Larry Jones and Nate Dove at First Baptist Church and Paul Pingel at Grace Lutheran for their help and conversations that provided a lot of background for this podcast. Thanks to Professor Paul Jones at University of Virginia for providing helpful advice and guidance. Thanks to my senior producer, Emily Gadek, and Kelly Jones, my editor for this project. And thanks to the University of Virginia's Religion, Race and Democracy Lab for providing a grant to support this project.