In 1815 Jesse Torrey, a Physician from Philadelphia, observed groups of enslaved people at work constructing the U.S. Capitol building. Torrey decried “the contradiction of erecting and idolizing this splendid…temple of freedom and at the same time oppressing with the yoke of captivity…our African brethren.”[1] The Capitol building occupies a place in our national imagination that the historian of religion Mircea Eliade might call a “sacred center,” a meeting place of heaven and earth.[2] The film shown in the visitor’s center today refers to the building as “a temple of democracy.” The ideals of American government take place here, in the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives. The contradiction that Torrey observed between the ideal of democratic liberty and the fact of American slavery remains present in this space.

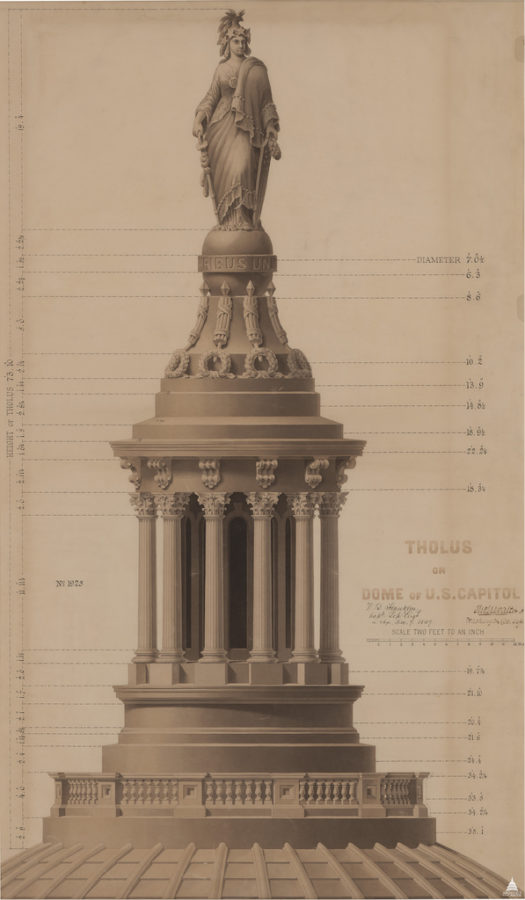

It is especially present in the art of the Capitol building. However, slavery is most present in its absence from the iconography of the Capitol building. Nowhere are enslaved people depicted. Art historian Vivien Green Fryd employs W.E.B. DuBois’s metaphor of “the veil of race” to explain the conspicuous absence of slavery from the building’s iconography, which was created in large part in years leading up to the Civil War.[3] DuBois claimed that white Americans fail to see black Americans, who are “shut out from their world by a vast veil.” Fryd proposes that the same veil hangs over the art and iconography of the nation’s capital. In this short audio piece, Professor Green Fryd unveils this act of veiling with regard to one especially prominent artwork: Thomas Crawford’s Statue of Freedom, which stands at the pinnacle of the Capitol’s iconic dome.

Recently, the nation has turned its gaze on other public images fraught with the history of American slavery and its underlying ideology of racial supremacy. We would do well to remember that disputes over such images are not new. How are we to view these contested images today? We might consider them among the most powerful symbols of our civil religion. Like a religious symbol, these images carry the weight of the past with them. They are accretions of history. However, their meaning depends as much upon how we behold them in the present – how we imagine our past in them now, and how, in turn, their imagery circumscribes the we of “our past.” An image implicates the viewer in its meaning. It leaves the viewer no choice. As the philosopher Hans Georg Gadamer writes, “the recognition of the symbolic is a task we must take on ourselves.”[4] Crawford’s Statue of Freedom may be easy to overlook. It flies high above the sightline of the casual observer. However, it demands to be seen again, to be recognized for what it shows, and what it does not.

[1] Quoted in Constance McLaughlin Green, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capitol (Princeton University Press, 1967), 33.

[2] See Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion, trans. Willard R. Trask (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987) 36ff.

[3] Vivien Green Fryd, “Lifting the Veil of Race at the U.S. Capitol: Thomas Crawford’s Statue of Freedom,” Common-place 10, no. 4 (July 2010).

[4] Hans-Georg Gadamer, The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays, trans. Nicholas Walker (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 47.

Additional Reading

Green Fryd, Vivien. Art & Empire: The Politics of Ethnicity in the United States Capitol, 1815-1860. Athens, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1992.

———. “Lifting the Veil of Race at the U.S. Capitol: Thomas Crawford’s Statue of Freedom.” Common-place 10, no. 4 (2010).

Meyer, Jeffery F. Myths in Stone: Religious Dimensions of Washington, D.C. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Additional Credits

Special thanks to faculty mentor, Jennifer Geddes, Associate Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia.

Get Involved

Learn about forthcoming podcast episodes, newly published projects, research opportunities, public events, and more.

Potential Students