Fresh Beats from Snoop to Euripides

Final Transcript

O’Reilly: On the religious front, another poll, very provocative. According to a Pew Research study of more than 35,000 American adults, Christianity’s on the decline. There’s no question that people of faith are being marginalized by a secular media and pernicious entertainment.

[O’Reilly fades out, Shapiro fades in]

Shapiro: There’s a lot of praise that’s put out for particular rappers, who it seems to me are doing something that doesn’t seem innately very difficult.

[Shapiro fades out, O’Reilly fades in]

O’Reilly: The rap industry, for example, often glorifies depraved behavior, and that sinks into the minds of some young people [...]

[O’Reilly fades out, Plato fades in]

Plato: There arose as leaders of unmusical illegality poets who were ignorant of what was just and lawful in music; and they, being frenzied and unduly possessed by a spirit of pleasure [...]

[All begin to increase in volume, abruptly cut]

Narration: For a large portion of human history, changes in music have been looked at suspiciously, especially when they challenge the status quo set by a political, racial, and religious majority. A couple recent examples should immediately come to mind: jazz in the early 20th century, rock n’ roll in the 1950s, and rap in just the last few decades. These musical changes are often labeled the downfall of “polite” society, a threat to traditional values.

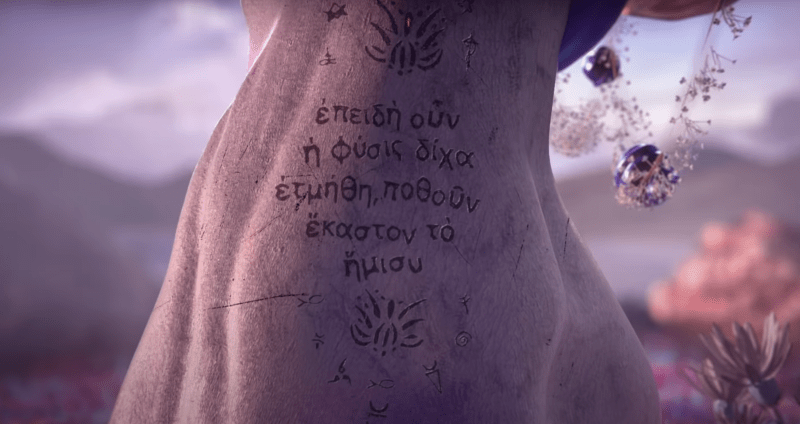

In ancient Athens, the development of the so-called “New Music” in the 5th century BCE was considered a very real threat to the upper class of Athenian elites. Young, innovative musicians created a new type of music loved by the masses and openly criticised by older, more conservative listeners. These critics said that the New Musicians were too showy to be considered “proper” musicians, and most importantly, they warned that New Music was a threat to the city of Athens itself.

Sound familiar?

O’Reilly: The rap industry, for example, often glorifies depraved behavior, and that sinks into the minds of some young people -- the group that is most likely to reject religion.

Narration: If you don’t know, that’s Bill O’Reilly, former host of the O’Reilly Factor on Fox News and one of the most outspoken “defenders” of American tradition.

[Armstrong’s Aulos Improvisation fades in]

Narration: It’s true, music is political. Both rap and New Music were significant indicators of social change within their respective cultures. But what is it about music that’s so political? How does it reflect social change? And why are conservative critics so worried about musical tradition?

[Armstrong’s Aulos Improvisation fades in plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Plato: Education in music is most sovereign, because more than anything else rhythm and harmony find their way to the innermost soul and take the strongest hold upon it, bringing with them and imparting grace […] if one is rightly trained, and otherwise the contrary.

Narration: That’s Plato. He wasn’t exactly the Bill O’Reilly of his time but he was definitely rich, definitely influential, and definitely interested in upholding aristocratic ideals and imparting them on the youth at his Academy. He had a lot of ideas about what a “perfect” society would look like, and quite a lot to say about music.

In ancient Greece, music was divided into particular modes, essentially types of scales, that were thought to foster different emotions. Plato believed that music had a particular grip on the human soul, was able to tame the spirit, promote good behavior, and, if misused, even overthrow states. Because of what it could do to people, music was inherently political, so learning the right modes was one of the most important aspects of musical education.

In a perfect society, Plato wrote, men (and only men) would be well-educated in music.

Specifically, traditional music.

Plato: [Overseers of our state] must be watchful against innovations in music counter to the established order, and to the best of their power guard against them [...] for a change to a new type of music is something to beware of as a hazard to all our fortunes. For the modes of music are never disturbed without unsettling the most fundamental political and social conventions [...]

D’Angour: Plato, who, looking back from the fourth century, having been educated in the late fifth century, would have heard traditional styles of music and also the New Music.

Narration: That’s Armand D’Angour, professor of Classics at Jesus College at the University of Oxford. He’s one of the leading experts on Greek music, especially New Music.

D’Angour: And he thought that the New Music was breaking the law of musical propriety, using the word "paranomia," “lawlessness.”

Narration: Athenian aristocrats like Plato were steadily losing power to the growing body of democratic citizens, and many of them clung to the traditions that they had held for generations, and one of these traditions was music. For a long time, musical education was reserved only for those with money and free time, and being able to play a musical instrument became a sort of status symbol for Athenian elites.

[A.D. Caron’s Letter Home fades in]

Narration: That began to change, though, when young, talented musicians began creating their own kind of music in the early 5th century.

[A.D. Caron’s Letter Home plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: The development of New Music in ancient Athens wasn’t all that different from the emergence of hip hop and rap in the 1970s. Like New Music, rap would eventually dominate the tastes and sensibilities of the 20th century “masses.” And also like New Music, rap was political from the start.

Carson: Hip hop is kind of made out of particular conditions. I think that where it comes from and how it is produced, how it’s disseminated and how it’s engaged is already political.

Narration: That’s A.D. Carson, assistant professor of hip hop and the global south at the University of Virginia. For Carson, it’s not just the criticism that makes rap political. Issues of race, class, and gender permeate lyrics -- and even the production of rap at its core.

Carson: I mean, you know, the very fact that, that people might comment that what they are doing is happening through two turntables and a mic. So you're already speaking to material conditions. Even when it doesn't seem as if rappers are saying anything political, I don't think that it's possible for you to remove those political layers from what you're engaging with and how it was made and how it got to you anyhow.

[The Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight fades in]

Narration: Rap was huge in the hip hop community before it entered the mainstream, where it began to face criticism from within and without. The first rap single to hit America’s top 40 was the Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 song Rapper’s Delight.

[The Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: Some people within the hip hop movement called The Sugarhill Gang sell-outs, saying that the culture would be ruined once it was commercialized. A lot of people outside the movement called the entire genre a “fad,” claiming it would be gone as quickly as it arrived.

It wouldn’t. Rap swept the industry and became so popular that it began branching into subgenres. One of the most famous subgenres was Gangster Rap, which broke the scene in the 1980s. And with it came even more controversy: over themes that explored violence, sex, and drug use.

Shapiro: From the outside, when I listen to hip hop, I don’t hear a lot of family-oriented messages. In fact, I hear a lot of messages that are degrading to women, I hear messages that push violence, that are disparaging to the police.

Narration: That’s Ben Shapiro, popular conservative pundit, internet personality, and one of the most outspoken critics of rap.

[A.D. Carson’s Second Amendment fades in]

Shapiro: I hear messages that very often seem to treat relationships between men and women as something disposable or glorify mistreatment of women… But, the art form overall, which obviously has a major impact not just on -- on Black young people, but is disproportionately listened to actually by white young people, I don’t particularly like a lot of the messages I hear.

[A.D. Carson’s Second Amendment plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: Critics like Ben Shapiro and Bill O’Reilly have a perception of rap that’s stuck in the 80s and 90s. Gangster Rap has largely fallen out of fashion and many of the most iconic figures of the genre have reinvented their image. Snoop Dogg hosts a cooking show with Martha Stewart. Ice-T stars on Law and Order: SVU, a far cry from his “Cop Killer” days. And yet Ben Shapiro and Bill O’Reilly continue to harp on rap as the root cause of violence in America, the harbinger of a social and cultural armageddon. They say that America is locked in a culture war, and rap is at the helm.

Carson: The violence that ultimately gets mapped onto hip hop, to rap performance is something that has, like, has never really gone away. [...] And therefore, you know, when people try to, to book rap shows, you know, venues are apprehensive. We need more security. We need more insurance. All of these, these kinds of things stuck. And they have been there for nearly fifty years, but, you know, are kind of just fabrications.

Narration: Those fabrications cover over something more sinister. Rap was and continues to be produced predominantly by Black artists. When that product is equated with violence, it’s easy for critics to then equate the creators themselves with violence.

[Hagel’s Kithara Improvisation begins to play]

Carson: Is, is Ben Shapiro's argument that America and the culture that it produces outside and around Black people is somehow less violent and less misogynistic?

Narration: It would be absurd if it wasn’t so blatantly racist.

[Hagel’s Kithara Improvisation plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: While the concept of race as we know it today didn’t exist in ancient Greece, Athenians like Plato used the concept of the “other” to indicate difference.

Athens is situated on the mainland of Greece, and across the sea was a series of Greek cities in a region known as Ionia along the western coast of modern-day Turkey. For a long time, the Persians -- who had been enemies with the Greeks for decades -- dominated the Greek cities in Ionia. And even after the Ionian cities regained their independence in 479 BCE, they still showed clear signs of Persian influence. Though they were technically Greek, they were “othered.”

Many of the New Musicians arriving in Athens in the 5th century were from Ionia. One particularly famous New Musician from Ionia was Timotheus of Miletus, whose music would have sounded very foreign, very “other” to the Athenian ear.

D’Angour: And that is something that we find embedded in some of Timotheus' lyrics, particularly actually a small bunch of lyrics where he says, “I'm doing something brand new and it's better.”

[Snoop Dogg’s Gin & Juice fades in]

Narration: What Timotheus is doing here is essentially the fifth-century BCE version of braggadocio, a type of boasting about being the best and the newest that permeates a lot of rap songs.

[Snoop Dogg’s Gin & Juice plays in isolation for a few seconds]

D’Angour: And the fact that he says that in that rhythm, I think it's pretty clear that he's doing it to say, “Look, here I am coming from the exotic east,” which is always where novelty comes from, you know, this famous idea ex oriente lux, ex oriente novitas, “from the east comes the new.”

Narration: Not all New Musicians were foreigners to Athens, though. One of the most famous proponents of New Music was Euripides, the Athenian playwright who wrote some of the best-preserved tragedies that exist today.

[D’Angour’s Rediscovering Ancient Greek Music fades in]

Narration: In fact, it’s from Euripides that we have one of the only preserved fragments of New Music.

[D’Angour’s Rediscovering Ancient Greek Music plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: You’re listening to Professor D’Angour’s reconstruction of a fragment of Euripides’ play Orestes. The fragment illuminates a few of the most important innovations in New Music for scholars like Professor D’Angour.

D’Angour: What I first noticed, even from the small scraps that we could transcribe, was that the words for “I beseech” and “I implore,” we could see that there was a falling cadence. [...] Shortly after that we have a word which suggests jumping up, we’re jumping up, up and down like a bacchant. [...] We're told by Skolias, an ancient commentator, that words, certain words were not sung, but they were shouted, and it clearly is an effect, a musical effect or even an extra-musical effect, and the kind of thing that no doubt would have shocked Plato.

Narration: These characteristics of the Orestes chorus, the non-musical exclamations and the use of tone to express emotion, would have sounded very unusual to an Athenian accustomed to more traditional music.

Critics associated New Musicians with maenads, the frenzied female followers of Dionysos, the god of wine who was himself said to be a foreign god from the east. Rather than contesting these criticisms, however, the New Musicians leaned into them, embracing this “othering” and composing high-emotion songs filled with feminine, eastern, and Dionysian imagery.

[Lil Nas X’s Call me By Your Name fades in and plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: We see musicians today doing the same thing. Conservatives like Bill O’Reilly rail against rap for making the youth reject Christianity, and so musicians like Lil Nas X purposefully play off those sentiments. His 2021 song Call Me By Your Name is a response to critics telling him to “go to hell” for his sexuality. In his music video, he does just that, pole-dancing his way to hell to the widespread outrage of religious and political authorities on Twitter.

Critics of Lil Nas X, Euripides, and Timotheus alike believed they were pandering to the crowds, cheapening their music to appeal to the whims of the masses.

D’Angour: I think Plato is fighting a rearguard action, the conservatives always are, they say, “Look, this is degenerate stuff.” But that's because tens of thousands of people in the theater and now millions across the digital world are enjoying it, and it's very much the staple of their musical life. And so what happens is actually it takes over very quickly as a style of music that people want to listen to.

Narration: The split between the type of music conservatives think we should listen to and what the people actually want to listen to reveals some of the underlying political tensions in these new genres of music. These conservative elites want to maintain the status quo because, in most cases, the status quo puts them in charge. Critics like Ben Shapiro openly admit their elitism.

Shapiro: So my view of this is shaped by the fact that I have the cultural profile of a Bond villain, meaning that, if I -- if I drank alcohol it would be brandy from a snifter, I’ve played classical violin since I was five years old, I own a nice violin, my dad is a professional pianist, we play Brahms together.

Narration: Shapiro is perfectly describing himself as a wealthy, educated aristocrat, one who believes that classical music is the highest art form and that music should continue to be produced only by musicians from elite institutions.

[A.D. Carson’s Talking to Ghosts fades in]

Narration: What we see in the criticism of rap and New Music is the division between those who want society to stay the same and those who are interested in using the political power of music to shape a different future.

Many rappers use their platforms to voice social and political issues that disproportionately affect the Black community, like police brutality and economic inequality. Professor Carson covers these sorts of issues in his dissertation, Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions. It’s the first-ever dissertation released as a rap album. You’re actually listening to it now.

[A.D. Carson’s Talking to Ghosts plays in isolation for a few seconds]

Narration: But some listeners ignore the social issues addressed in albums like Owning My Masters, choosing instead to focus on the negatives of the genre.

Carson: I mean, I recall a time when I lived back in Illinois that I went on to a conservative, a conservative radio show to talk about a project that I was doing, you know, with the high schools. And the interview that I had with the person was, I don't know, it was a cool interview, you know, standard kind of thing, you know, people ask, you know, silly-ass questions about hip hop and what it might mean and what it could do, you know, and all of this. And then within two days, you know, like that, it turned from this being a really cool thing to “Have you seen the music that this guy puts on YouTube?” Same guy, same interviewer. You know, these folks dedicated, like, a thousand times the effort and energy to being outraged by the kind of music that I made than they did put into this thing that I was doing with young people in town.

Narration: Critics like this radio show host choose to overlook the work these rappers do and the social issues they comment on, focusing instead on explicit tags and lyrics and arguing: young people listen to rap, rap is sometimes violent, young people are sometimes violent, and therefore rap is corrupting American youth.

But meaningful discussion of social issues and explicit language are not mutually exclusive. Similarly to how conservative pundits use inflammatory language to provoke their audience, rap artists often use explicit language in order to elicit an emotional response in their listeners. Kendrick Lamar, perhaps one of the most decorated rappers of our time, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for his album DAMN, tagged as “explicit” and sampling a Fox News segment criticizing his performance at the 2015 BET Awards.

[Kendrick Lamar’s BLOOD fades in and plays in isolation for a few seconds -- crossfades to A.D. Carson’s The Song I Should Have Written]

Narration: Professor Carson’s dissertation, also tagged as explicit, is widely acclaimed for its social commentary. His “See the Stripes” campaign, named from a track on the album, raised awareness about the historic racism at Clemson University. In 2016 he was awarded the Martin Luther King, Jr. Award for Excellence in Service at Clemson.

Professor Carson theorizes that people like that radio host back in Illinois focus on the negatives of rap to gain the support of their conservative listeners.

Carson: I don't know that this person has a personal vendetta against me. I know that this person wants the ratings that they get in this small market in this little Midwestern town, and it’s much easier to engage people when you get them pissed off about something. And so, yeah, I took that shit personally, but I know it wasn't about, it wasn't about that guy and me, it was about the way that that guy is able to engage his listenership.

Narration: There’s no doubt pundits talk about controversial topics for attention. Clicks and views do turn into dollars. But they really do believe that rap is threatening -- they just aren’t quite honest about what they’re actually trying to protect.

[Hagel’s Kithara Improvisation fades in]

Narration: New Music was emblematic of the kinds of political change happening in ancient Athens. Aristocrats were slowly losing their power to the democracy, the power now resting in the hands of the people rather than the few. When aristocrats like Plato attacked New Music, it’s clear that music was just a stand-in for what they were really afraid of.

Plato: By compositions of such a character, they bred in the populace a spirit of lawlessness in regard to music, […] and in place of an aristocracy in music there sprang up a kind of base theatrocracy.

D’Angour: So there is Plato seeing this huge sway of popularity for a kind of music that he associates with the wrong kind of people, people who are really the masses, the demos. They're not the people who have the refinement to play the lyre themselves. And so he thought, “Well, I've got to philosophically explain that it's not the right way for music to be.” And it's been hugely influential so that people have tended, scholars have tended to say, “Well, you know, Plato says that music degenerated in his youth.” Well, actually, clearly didn't. It just developed in a way that Plato didn't like.

Narration: Critics like Bill O’Reilly, Ben Shapiro, and Plato are concerned about the integrity of music only as far as it goes to maintaining the status quo, a status quo in which wealthy, educated aristocrats like them sit at the top of the pecking order. Music is an especially effective platform for traditionally silenced voices to make themselves heard, with Black artists from New York to non-elites in the city of Athens alike being able to make a name for themselves and gain renown in a system designed to keep them quiet.

[A.D. Carson’s Letter Home fades in]

Carson: But, you know, it's, I don't know, it's an effective trick that folks are always asking about the responsibility of rappers, you know, for the negative things that America does that is exhibited in the music. And so it really doesn't give it doesn't give hip hop, it doesn't give rap music a fair shake. It's insinuating and then, like, asking the defense for all of the bad, but then never taking or never even acknowledging the things that we might see as more positive.

Narration: It’s the democratization of music that critics fear and why they purposefully ignore the good in these new genres: their role in the evolution of music, their positive effect on so many listeners, and their ability to foster important political and social change.

- - -

This podcast was written and produced by me, Abigail Bradford, for the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab at the University of Virginia with the help from the Lab’s Senior Producer, Emily Gadek and the Lab’s Editor, Kelly Hardcastle Jones.

Special thanks to Professors Armand D’Angour and A.D. Carson for participating in the project and to Professor Hamner Hill for providing the voice of Plato. Thanks also to Professors Tyler Jo Smith and Dylan Rogers for their support and encouragement in pursuing podcasting as a medium for telling stories about the ancient past.

This project features music by A.D. Carson, Armand D’Angour, Barnaby Brown, Callum Armstrong, Stefan Hagel, The Sugarhill Gang, Snoop Dogg, Lil Nas X, and Kendrick Lamar.

You can find more documentary research on religion, race, and democracy at religionlab.virginia.edu. Thanks for listening.