Race, Religion, and Democracy Lab

Mauna Kea and the Sacred

Transcript

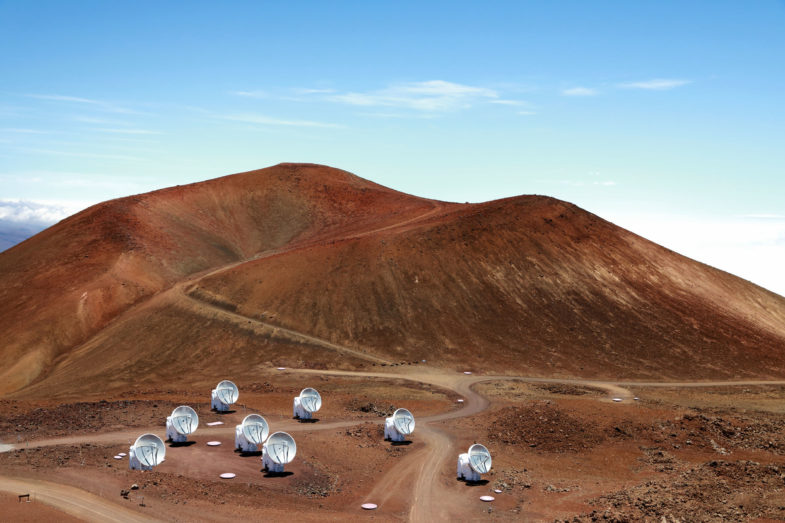

Matt: Ope you can kind of see the telescopes.

Heidi: Oh yeah, what do they look like as we’re driving up?

Matt: White pimples. That's a terrible descriptor. No, but really, like, I don't know what other way to put it. You know, there's now, what? Like 13 or something like that.

Narration: [Matt]Heidi and I were driving up from Hilo to Saddle Road, to visit the Pu'uhonua, the place of refuge, that protectors of Mauna Kea had set up a few months before.

Narration: [Heidi] Matt had been living in Hilo. He had visited the Pu'uhonua, and attended a seminar at the university about Mauna Kea and its sacredness.

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: It is where in our Hawaiian cosmology, our Earth mother and the Sky father meet. And it's from that union that the mountain was born where constellations were formed, where eventually the humans in the genealogy of mankind that emerges.

Noe: My name is Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson. I am a mauna kupuna. That's what we call ourselves. I am an elder.

Narration: The summit area of Mauna Kea is called the wao akua or realm of the gods. It is the home to Hawaiian deities. Including the goddess Lilinoe--“the mist that meanders over the mountain.” She tends to Poliahu, the snow goddess referenced in the ʻōlelo noʻeau or Hawaiian proverb:

Reader: Poliʻahu, ka wahine kapa hau anu o Mauna Kea / Poliʻahu, the woman who wears the snow mantle of Mauna Kea.

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: It is where man cannot live. There is less than 30 percent of the Earth's oxygen, up at the 14,000 foot level. So literally a human cannot survive there for any length of time and be healthy. So. So it is not a place where humans belong to begin with.

Narration: But since the early 1960s, humans have been on Mauna Kea almost every day. That’s because settlers and scientists started to build telescopes on the mountain. It’s become famous for its “unique astronomical conditions” including cloudless skies, scatter free atmosphere, easterly trade winds, and very little boundary layer turbulence. As the tallest mountain in the world from base to peak and with its location in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, Mauna Kea offers isolation from human made light sources.

Switch Narrator: There are now thirteen telescopes atop Mauna Kea. They vary in size, range and technological sophistication. Scientists have been planning a fourteenth –a Thirty-Meter Telescope - or “TMT”. It would be the largest development built on the summit of Mauna Kea. And, astronomers argue that it would allow them to see deeper into space and with more detail than any of the other existing telescopes elsewhere, or on Mauna Kea. But for Hawaiians, there is

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: What's at stake is just more and larger desecration of the summit area of the mountain, which is the most sacred area of our mountain. Our community has been unhappy about the development of the summit area of Mauna Kea, which we consider a papa lani or a wao akua, the most sacred part of the mountain.

Narration: There’s a battle going on over this part of the mountain - and who has claim to it and why. Those standing for Mauna Kea call themselves kiaʻi, which translates to guardians or protectors. These people are standing for the place they consider their living ancestor as traced through the Kumulipo or Hawaiian creation chant. Moreover, kiaʻi and their allies are standing to protect the life of the land that is rightfully theirs. Especially in light of ongoing U.S. colonialism that began with the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and has continued through increased settlement, military presence, and the rise of tourism after Hawaii became a state in 1959. .

Narration: On the other hand, settler-scientists, backed by the University of Hawaiʻi and the State of Hawaiʻi government are pushing for the Thirty Meter Telescope through the rhetoric of scientific advancement and discovery--much of which brushes over or ignores completely the importance of Mauna Kea to Hawaiians and the mountain’s place within Hawaiian cosmology. This “science at all costs” approach of the TMT and its proponents is ultimately a continuation of U.S. colonialism in Hawaiʻi and is the source of a lot of the tension not only between kiaʻi and TMT proponents, but within the astronomy community as well.

Lanakila: The Supreme Court of Hawaii on their second ruling to grant this project says, well, we've recognized now that based on the concept of degradation, they're allowing further construction because we see there has been so much damage, we don't feel that one more big project is going to make much of a difference.

Narration: This is Lanakila Mangauil, mauna kiaʻi and candidate for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs:

Lanakila: That for us is, "we have always stabbed your grandmother 13 times, so one more time should not make a difference.” What is happening here? What are we setting forth for future generations? As we look into the heavens for guidance, don't forget to look down at your feet and where you are.

Pua Case: If you would just take a moment to pause from your busy day and think about the most sacred place that you are connected to. The place that brings you peace and accepts your prayers. The place where your God dwells. Very likely the place where your grandparents and their parents once prayed.

Narration: This is Pualani Case, a kia’i, or protector of Mauna Kea and an opponent of the TMT. Pua and fellow Kia‘i are addressing astronomers, supporters, and members of the press at the Annual Conference of the American Astronomical Society.

Pua Case: The place you would safeguard with all of your might, with all that you are, and all that have. If you said the holy name of that place out loud, what would it be? Would it be the name of a church, or a temple or chapel you hold dear. Say it. Say it.

Narration: Sacredness, one might say, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. What is sacred to one person, may not be to another. But that is not what is really going on in the struggle between kia’i and the proponents of the TMT. Many proponents have admitted that Mauna Kea is sacred, either as a sacred site of Native Hawaiians, as a unique place geographically, ecologically, and astronomically, or as both. The struggle is over relationships, who has them, who claims them, and which kinds of relationships the government supports. What remains true through these struggles is that sacred sites are worth fighting for even in the face of colonial violence because of the kinds of relationships to land and to one another that they make possible.

Narration: For Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua, Mauna Kea is one such sacred place that she and other Hawaiians would safeguard with all their might. In July of 2019, kia’i and their allies, like Noelani began physically blocking the roadway from construction trucks and crews.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: Well, the day that we ended up chaining ourselves to the cattle guard. That was July 15, and probably, I would have to say, was one of the best days of my life in a lot of ways.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: So it was just this day where it really felt like so many people were coming together with a common purpose in alignment with the mauna. And it felt like there just couldn't be a better time to be alive and to be Kanaka. And ...to be someone who is standing in defense of the land.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: It, it really is about being joyful to renew our connection, our connection with the ʻāina.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: Aloha ʻāina is a very, very old guiding value, an ethic and practice. We know that it's so old because of all of the ways that Hawaiian language, whether it's in song or proverbs, honors land and writes about land and the elements. And it's just so embedded in Hawaiian literature and poetry and orature. But it also has come to mean patriotism and the kind of activism that is around protection of places.

Narration: Aloha ʻĀina also has a long history within movements for Hawaiian sovereignty. These movements have been alive and growing since the illegal U.S. overthrow and annexation of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: So in the late 1800's, a little I know was a model of Kanaka who were defending Hawaiian independence against U.S. annexation. In the late 1970s, it was a way of expressing protection of Kahoʻolawe against bombing.

Lanakila Mangauil: Aloha ‘āina, malama ‘āina are just terms that we grew up with. That it is interesting that when I talk to my father who was a Kanaka Maoli he never heard that stuff. Because they weren’t allowed to do that. My great grandmother was the last speaker of Hawaiian language in our family. She was the generation that was beaten for speaking that. So she never taught my grandmother, my father never learned and with the loss of language is the loss of the comprehensive of the amazing amazing records of history of our people.

Narration: ʻĀina, the Hawaiian word for land, literally translates to “that which feeds.”

Lanakila Mangauil - And Aloha is a description of what we're mandated to abide by. Which is every context of what aloha means is really the core of being respectful and showing gratitude and love and care and consciousness of where you are. ...So as you approach someone or some place, to really take notice of where you are. Understand who you're connecting with or what you're connecting with. And then check your relationship that you're going to engage with them so that you're not detrimental.

Narration: Aloha ʻāina views the life of the land and human life are interconnected. That’s a very different perspective than a lot of American environmental advocacy, which views nature as something that needs to be protected from humans.

Matt: So the west kinda has this “set it and forget it” notion of environmental policy which is the antithesis of an ethic of care that values relationships with the environment. The western approach is like, just lop off a section of land and call it a “wildlife sanctuary.” As a fisherman here in Hawaiʻi I see this all the time. As a fisherman, however, I know that I have a relationship with the areas I fish. And with this relationship comes kuleana or responsibility to care for these places. There also comes knowledge of how to care for place because as fishermen we spend so much time on the water. With the rise of tourism and military folks trashing the beaches like we saw here during Memorial Day weekend, it’s even more important that those who know the land and how to care for it--like fishermen or cultural practitioners--retain access. We’re often the ones cleaning up the beaches from the messes left by tourism, militarization, overdevelopment, and overpopulation. So relationships and access to land are essential to protect and care for it--as are the people who have this knowledge. Now, I wouldn’t dare equate my fishing practices with aloha ʻāina, which is much deeper and more complex than the examples I’m giving here. Instead, I credit a lot of the fishing practices that I have adopted to the old timers I have learned from and the Hawaiian scholars and activists whose work on aloha ʻāina, kuleana, and pono (which means balance or harmony) I have read. And as a settler, that’s been a big part of the ways I am continuing to try and decolonize myself.

Narration: Aloha ʻāina carries with it the responsibility or kuleana all of us have to care for that which feeds and sustains us--a responsibility that continues to be taken up by those standing in solidarity with Mauna Kea.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: And today, it continues to be used as a phrase that captures the protection of that relationship between Kanaka and ʻāina that is one of love and reciprocity and family.

Narration: Love, reciprocity, and family. That has always been at the core of the Mauna Kea movement.

Narration: Aloha ʻāina actions for Mauna Kea--for the health and abundance of Hawaiʻi for that matter--are deeply grounded in kuleana.

Pua Case: Kuleana is a word for responsibility, everybody. So no matter where you go to, perhaps this is the way we would see our guidelines close on the mountain. No matter what you do in your field and us as well, we impact, not just imprint, we impact.

Narration: Kuleana is also about relationships--with land, community, and the spiritual. For kiaʻi, these relationships have been built through an intimate knowledge and connection to Mauna Kea.

Pua Case: I've spent 10 years every day aligned with Mauna Kea. I know my big momma and I stand with Her because I'm born and raised. And even if you aren't and you don't have to be, I am. So my Kuleana has been laid down for me.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: So kuleana is an ethic, a practice that I understand where it often gets translated as responsibilities or authority.

So like I was saying with the puʻuhonua, I see my kuleana over there as as a kakoʻo or as a supporter to the people who are more central. Who maybe have direct genealogical lineage to Mauna Kea, maybe have people or members of their family who are buried there or who have had their piko or their umbilicus deposited on the ʻāina. Or who have just spent a ton more time on the island, you know, who reside there, just different stakes. So that's all part of kuleana, too.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: But it really has to do with place and genealogy as well. So the things that you have to do or that you should do based on your responsibilities, given your positionality, given your genealogy, given your relationship to a particular place.

Narration: We all have connections to place? Don’t we? And yet, as demonstrated by the 13 telescopes and the proposed Thirty Meter Telescope, indigenous connections to place, to ‘āina, have been ignored in decisions by the settler state or actors in the scientific community. So what does it look like to recognize and support these connections, to stand with Mauna Kea?

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua:I think it looks like a lot of different things. You know, whether you're able to actually physically be present or whether you're supporting from various other locations.

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: Every day we get visitors from throughout Hawaii and then from the continent and around the world and they often bring flags with them from their tribes, their nations. And as you can see, we now have. Over 50 flags, most of them which are flying, but we have another several flags that are still yet to be exhibited. ...We have flags from Sweden, Czechoslovakia. Throughout the Pacific, of course. Micronesian islands. Throughout Europe. Spain, Portugal and through Asia, we have the Taiwan flag, the Japan flag. And then we have several Native American nations and First Nations people from Canada. So they brought their flags to show their solidarity, their support for who we are.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: Ultimately, I think at the core of it is helping to support and create space for the relationships of connection between Kanaka and ʻāina.

Narration: Alliances and solidarity are also built into the thrice daily ceremonies, or aha, on Mauna Kea--a protocol of several chants, or oli, and dances (hula) in alignment with the mauna. And while some parts of the aha are reserved specifically for Hawaiians, other parts encourage active participation by all.

Lanakila Mangauil: The protocol of the aha we begin with general prayers and then we have what we call hula hoʻo ilina, which are dances that come from particular hula schools.

Lanakila Mangauil: And we request that you have to go through a little more training on because they're, the energy behind them needs to be a little more tailored because it is not just a reminder for us, We're actually enacting and sending this energy to the universe to help push what weʻre there for. And then the hula noa. Those are a number of dances that we've selected to have a little bit more freedom for people to be able to participate, because a big thing in this movement too is it's all participation. It's about the collective consciousness.

Narration: And so these alliances--whether through visiting the mauna and bringing a flag or supplies, tuning in via social media, or being part of the aha--all work to build connection. These connections form relationships which ultimately inform a kuleana--a responsibility. And by recognizing the sacredness of these connections and the kuleana they are tied to--to people, to land--we are further pointed toward standing with Mauna Kea.

Narration: Amy Kalili, Hawaiian language scholar-activist, explains the significance of this relationship and how pilina might foster communication between TMT proponents and mauna kiaʻi:

Amy Kalili: A couple of things that I touched on in my talk were about the value and importance of pilina, which is the Hawaiian word for relationships and building relationships and hoʻokaʻa ike. Which is Hawaiian word for communication. And there seems to be this recurring theme where there has been arguably a lack of that in some situations just truly being able to establish relationships and keep open lines of communication.

Narration: Pilina or relationships also translates to “an intimate tie with another entity.” The kuleana of mauna kiaʻi to protect her from further degradation is thus directly tied to the genealogical, spiritual, and cultural connections shared with the mauna. A better understanding of pilina, along with better communication between TMT proponents and kiaʻi, can ultimately open up possibilities to better care for Mauna Kea and offers settlers and scientists a way toward understanding its significance within Hawaiian cosmologies and worldview.

Narration: Thinking about alliances, relationships and the process of building both of these in regards to Mauna Kea ultimately begs the question of “Where do we go from here?” Indeed, it is a question of futurity--who gets to decide the future of Mauna Kea? Along what lines? Moreover, what do the past, present, and future decisions regarding the mauna imply not only about its sacredness, but the right of the Hawaiian people to self-determination and sovereignty?

Narration: Dr. Noelani Goodyear- Kāʻopua discusses the kinds of futures, or futurities, as they are often discussed, that are possible given ongoing colonization.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: So the futurities, as I understand them, are ways that people think about, represent and come to know or have relationships with various potential futures.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: So settler futurities ways of thinking about futures that foreclose indigenous connections to land and where the impulse of settler colonial system the power is to remove or substantially contain indigenous peoples in order to make space for settler societies. Settler futurities are about severing or minimizing and marginalizing those connections so as to make space for settler societies and ways of using land.

Narration: Perhaps one of the biggest ways settler futurities are being pushed by pro-TMT folks is through the language used to describe kiaʻi standing with Mauna Kea.

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: Likewise, there are a lot of people who are critical of us because they think that we're just blocking the road or we're just being obstinate or we're not willing to move into the 21st century. You know. Weʻve heard that as well.

Narration: Indigenous futurities, in contrast, provide ways to perpetuate and renew relationships to the mauna, and ʻāina more broadly, in a more reflective and conscious posture. As Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada explains in his article “We Live in the Future, Come Join Us:”

Reader: “Our genealogies are a backbone stretching to the very inception of these islands, and when we understand our genealogy, we know our origins, where we have been. We always have our ancestors at our back. That certainty gives us a wider possibility of movement, a more supple way to navigate through the world. Standing on our mountain of connections, our foundation of history and stories and love, we can see both where the path behind us has come from and where the path ahead leads. This connection assures us that when we move forward, we can never be lost because we always know how to get back home. The future is a realm we have inhabited for thousands of years.”

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: Indigenous futurities are different in that they don't require the erasure or removal of peoples in the same ways that settler futurities do. But they do require all peoples to come to recognize in some way their relationship and impacts on place. And with each other.

Narration: Indigenous futurities ultimately point us toward care--a care that comes from an understanding of the sacredness of Mauna Kea. A care that, in light of this sacredness, is rooted in aloha ʻāina and kuleana-- not only to the mauna, but to our ancestors, each other, our children, and the land itself. Indigenous futurities encourage us to reckon with the rhetoric of progress touted by capitalism and the occupying settler-state and continue to instill a sense of resolve in kiaʻi around the world standing with Mauna Kea.

Narration: Whatever happens with the TMT, the thirteen telescopes on Mauna Kea are still operating. While the protectors have blocked construction equipment, they haven’t stopped research on the mountain. And, in what might be surprising to some, Protectors of Mauna Kea continued to allow settlers and scientists access to the mauna because of this love and care for the ʻāina.

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: We allowed for the telescope workers to continue to work even during this particular time that we've been sitting on the road. We do that because we don't want any further damage on the summit. So we wanted to make sure that the existing telescopes continue to work in good, good condition and don't pose any other environmental damage.

Dr. Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua: And I hope that my colleagues who are in the natural sciences, although they aren't subject to the same kind of institutional and federal laws around research, will still feel compelled to think about what ethical research means. And, that if you have to arrest large numbers of people, of a particularly of indigenous people of that place, that maybe there's something wrong with the way that you're going about doing your research.

Dr. Noenoe Wong-Wilson: We're committed to be here till the end. This project projects a 10 year construction time. We're trying to inform them now that if they insist on moving forward, we're going to be here for 10 years, fighting them every way, every step of the way.

Narration: He ali‘i ka ‘āina, he kauwā ke kanaka, “The land is the chief, man is its servant” – Mary Kawena Pukui, ʻŌlelo Noʻeau.