Tolliver: How would you describe him?

Wayne: [01:27:12] Well driven, driven, deliberate, focused. Once he puts his mind on something, he follows through on it. Caring individual. Willing, willing to take care of those responsibilities in which God has entrusted him to. [32.9s]

Tolliver: That’s Wayne Booker, describing my dad, Gary Mance. Wayne went to highschool with my dad and they’ve been close friends ever since.

In my words? I’d say my dad is one of the calmest, quietest people I’ve ever met; even incredibly shy and reserved within my own family. I wouldn’t imagine him ever stirring things up or leading groundbreaking change. But, my dad was one of the first Black students to integrate an upper-class, white, southern all-boys boarding school in rural Virginia.

It was a challenging but important time, and still to this day what he would say shaped him perhaps more than anything else in his life.

[MUSIC]

My dad grew up in Orange, Virginia in the 60s. It was - and still is - a small, rural farm town about a hundred miles south of Washington, D.C. He was raised by his grandparents while his mother worked in Washington.

Gary: [00:12:40]My grandfather worked for a feed company. [7.0s]

[00:12:49]Basically, they made grain for different places, for farms, for a lot of different places that will come and pick up the feed. [14.5s]

Gary: [00:13:26]My grandmother. [0.2s] [00:13:31]Was a kind of like a housekeeper for two different white families. She would go to those houses and she would alternate different each day from one house to the other house, and she would clean the house and make meals and kind of help take care of the kids that were their kids as well. [28.7s]

Tolliver: When my dad was a kid, LBJ was president, afros were mandatory, and segregation was still rampant.

Gary [00:18:04]I could not go into a certain part of a theater to watch movies. We never saw a movie indoors. We were relegated to going to the drive thru. That's all that we could do as kids. And we really had different fountains to drink at the black fountains compared to a white fountain. [45.5s]

Tolliver: In Orange, Virginia, Black families very clearly lived in one area of town. White families lived in another. But my father actually had white neighbors who he played with along with his aunt and uncle, Michael and Michelle, who were also his same age.

[AMBIENCE - NATURE SOUNDS]

Gary: [00:06:37] And we all played together. We played many different games. We played hide and seek. Sometimes we would climb trees together. Sometimes we would go deep into the woods and investigate things and find small animals or algae. We'd go bike riding together. and we would ride about, well, five, three miles down the road and just hang out and see people as we'd ride down the road. We would challenge the other neighbors further up the road to play softball with us. [79.1s] [00:07:59]We would do our chores each morning. Chores would be things like we had a wood burning stove. So we bring in the wood for that stove. [41.2s]

Tolliver: Even though my father has fond memories from his safe childhood, at the time his grandparents knew what the world wanted to do to a young Black boy in the 1960s. Having already raised 4 Black children into adults, they made a conscious effort to instill important values in my father. And it started with the Church.

Gary [00:22:42]The main value that I was raised with was to respect your parents and to respect others and be open minded to others, thoughts and ideas. Very much grew up in a religious home. [24.1s]

00:35:18 Just about every. Black family that I knew went to church, we didn't all go to the same church because there were several different black churches in our area, but we all went to church and at different points in time, we would come together and be at the same church because they would have what you call church homecomings, and they would invite one black church to another black church. And that's when we would see some of our neighbors at their black church. [55.9s]

Tolliver [00:25:05]What kind of church did you go to? [1.9s]

[MUSIC]

Gary [00:25:08]Oh, it was a Baptist church, so we were certainly Southern Baptists, individuals [7.4s]

Tolliver [00:25:27]how much would you say that religion shaped your upbringing? [2.9s]

Gary [00:25:34] I would say it was a significant part of our life. We respected the Bible, we were God fearing family, and it was it still is a part of my life. [24.6s]

Tolliver [00:26:57] Did you see your grandparents going to church as a time for rest, for recuperation? What was that like for them? [11.4s]

Gary [00:27:11]It was a it was a social event for them other than a religious event. They got a chance to see their friends. We as kids would when the service was over, we were able to go and get in the car and be ready to go. But we would always be waiting for our grandparents because they were socializing with all their friends. And it was the only time they got to socialize with them during the course of the week. And so we'd wait patiently until we'd all leave and go home. [44.0s]

Tolliver: So, my dad grows up in Orange, Virginia like many young Black boys did: doing his chores around the house, going to church every week, and playing outside. At his young age, he didn’t understand segregation, and he was accustomed to playing with Billy and Brenda every day, which is why he was so confused when it was time to go to segregated schools for the first time.

Gary [00:18:04] And clearly the biggest difference that stood out to me was that we went to black schools and and there were white schools that were separate.

Gary [00:41:19] When it came school time. There was two busses, one bus went right by our house and went to the white schools, the other bus came and took us to the black schools and the white school was less than five miles away from my house. The black school was probably 20 miles away from our house. And we were bussed there to go to the black school. And we had all black teachers, um, we had a black principal. And that's where I learned things. And I thought it was a great school.

Tolliver: My dad’s school had older, used desks, books, and projectors, but that didn’t make a difference. He loved his school and was surprised when he found out he’d have to leave it.

Gary [01:04:07]I was told, when I was going into the sixth grade that I would no longer be going to the black schools that I had been going to from the 1st to the 5th grade, that I would now be going to the school five miles up from us, which were white schools. [20.1s]

Tolliver: This process of integration was nearly 10 years after the Supreme Court overturned segregation in American schools. Orange had attempted to integrate its public schools earlier, but this was met with resistance.

Gary [00:26:31]You know, there was one black principal in Orange and he tried to. Kind of integrate as much as he could, but he was probably a little fearful of some things because he did have a cross burned in his front yard. [24.9s]

Tolliver [00:27:13]Did you did you know what that meant? [1.4s]

Gary [00:27:17]I knew what that meant. Yeah, I knew what it meant. [2.2s]

Tolliver: But Orange finally did start integrating around 1967, and my father moved to a new school, previously known as “the white school.”

Gary [01:09:01]When I first went to the integrated school, the first thing that stood out to me was. I had white teachers. I had never had white teachers before. [15.9s]

[01:10:10]There’s a great deal of difference between a white adult and a black adult in a school setting, a black adult in the school setting. They showed a lot more concern and nurturing to me as a black student. They cared about me. They cared about my well-being. They cared about what I learned as the student. The white adult taught me things in school but really didn't relate to me as an individual. And they related probably more so to the white kids than they did to me, I was just another student. [52.9s]

Tolliver: He wasn’t only disconnected from his teachers.

Gary [01:14:33]So once I get to my class and I'm in integrated class, I realize that a lot of the black friends that I had, that I went to school with from the 1st to the 5th grade are not in the same class that I am, even though they're the same age as I am. And we'd been together for years. And so I find out during recess they're in a different class and then all of them are together in this other class. [41.2s]

Tolliver [01:15:15]So you're like, I want to go there. [2.2s]

Gary [01:15:17]Yes. That's exactly what I want to do. [1.4s]

Tolliver: [01:16:09]So when so did you go to your white teachers and ask them, hey, where are all my friends? [5.9s]

Gary [01:16:15]: And they said you were. More advanced than they were, I guess that was the term that they used, I don't remember the exact wording. Yeah. [22.7s]

Tolliver: Since my dad’s new school had placed the majority of the Black students in special education classes, he now was not only in classes with white students for the first time, but he was one of the only Black students. It was very different, and certainly not easy, but he was about to find out that it had only been a small taste of something far more difficult.

[MUSIC]

My father was finishing eighth grade when he first heard about Woodberry: an all-boys private boarding school only 20 minutes from his home. It was now 1970, 16 years since Brown v Board of Education, and Woodberry Forest finally decided to look in the surrounding counties for the six brightest Black boys to integrate the school. A supervisor in Orange came to my father’s house and asked his grandparents if he’d take the placement test. If he passed, he’d be accepted with a full scholarship for his tuition.

Gary [00:07:15]I had no idea. I I'd never heard of Woodberry before. I had no earthly idea. But she came to me and asked me and I said, why would I want to go to Woodberry? I said, I got all my friends here in orange and why would I want to go to that school? I don't know anybody. And my mom came to me, too, and said, do you want to go to this Woodberry? And they told me about Woodberry, you know, the great school, great academics. You can really excel in life. And I'm like, I'm fine. I'm a kid. [46.2s] [00:08:08]And so my grandmother really set me down. [4.0s] [00:08:51]she came back and. Convinced me that that was the place to go. That it was going to make a huge difference in, you know, my life going forward. [12.2s]

Tolliver: My dad then went to take the placement test. He was blown away by the size and grandeur of Woodberry, but he remembers feeling calm and not at all nervous - his only concern was letting his grandmother down. After three weeks he got his results: he’d been accepted.

Gary [00:10:24]Wow, I was impressed, actually, when you pull into the area and you see that big building. It's impressive. So I was impressed with the building and I was not scared. [20.6s]

Gary [00:14:38]I was like, OK. That's where I'm going to school. Now, the shocker was. Probably about a couple of weeks later, they told me I had to go to summer school. And I said, oh, I do. [18.4s]

Tolliver [00:15:02]Like you saw that as a bad thing. [0.3s]

Gary [00:15:02]I definitely saw that as a bad thing because I've never been to summer school. I'd always been a great student. I figured that people that had to go to summer school were people that couldn't do their work during the regular year. So they had to catch up on summer school. [19.2s]

Tolliver: It was even worse that summer school conflicted with Bible camp.

Gary [00:15:40]That was like. The greatest thing in the world for me to go to Bible camp because I would meet. Kids in orange, and maybe even a couple other counties close by, we would all go to this camp. [70.2s]

Tolliver: After embarrassingly being picked up early from Bible camp by his grandparents, my dad set off for summer school. He found out he’d have to stay on campus all three weeks with a white roommate, but to his surprise and relief, they got along very well.

Gary [00:27:42]Now, the cool thing was because, you know, he was a little more privileged than I was. So he had some neat stuff. I mean, he had a nice record player. Um, I had a couple of records, but he had a lot of records, so we’d listen to his records and, His parents would send him care packages. And a lot of food and stuff, and he shared it with me and I thought that was pretty cool. [43.6s]

Tolliver: However, in the classroom, things were much more difficult.

Gary [00:29:46]I definitely realized right away that this school is going to be much tougher. I'm going to have to work a lot harder to do that. [8.8s]

Tolliver [00:29:55]Is that when you started to get nervous because up until this point, you have not been nervous. [3.1s]

Gary [00:30:03]I can tell you right then and there I knew and I was definitely nervous because I'm thinking, oh, my God, am I going to be able to do this? [8.7s]

Tolliver [00:30:13] did you feel like you had to prove yourself because you were black? [8.6s]

Gary [00:31:08]That was one thing that my grandmother told me before I went there, is that I have to do well because I'm representing all black students and that if I did well, that others could follow me. So I could not fail in her mind,. [25.9s]

Tolliver: With his grandmother in mind, my father made it through summer school. But…

Gary [00:43:07]All of a sudden, they come back. To me,. [3.0s]

Tolliver [00:43:10]Uh oh. [0.3s]

Gary [00:43:12]And say, I would like for Gary to go out for the football team. And we have summer practice before the school starts. [14.9s]

Tolliver [00:43:28]So at this point, you guys just won’t give me a break. [1.9s]

[00:43:31]That's my summer break. [4.5s]

Gary [00:43:38]I'm just like, oh, my God, it's just overwhelming. [2.1s]

[00:43:57]But that was also like, oh, my God, I got to go back to the school again. And I'm going to meet a bunch of white boys now, and I don't know anybody, [15.1s]

[00:44:31]And if the coach was going to give me a hard time, I didn't know how good I was going to be compared to them, because some of them have been playing football for several years because, you know, when you get on a football team and they put me on the varsity football team, so I was a freshman and they put me on the varsity football team and, um. You know, some of them and playing together for three or four years, and so I was really apprehensive.

Tolliver: And he had reason to be.

Gary [00:46:31]They weren't too they weren't too happy with me. [3.3s]

[00:46:58They didn't care for me at all. Yeah. And the only person that was happy to see me. Was the, uh, the guy in the cage, is what we call it, it was a black guy that gave out all the equipment each day. [19.2s]

Gary [00:47:20]He worked for the school and he gave out all the equipment, gave you a jersey and all that stuff because they cleaned it every day you need wear it and then. he was excited and he was somebody I could talk to because he looked like me. [31.1s]

Tolliver [00:48:45]And were you the only black kid there for summer practices? [3.5s]

Tolliver [00:48:52]Like, that was hard, right,. [1.0s]

Gary [00:48:54]Wasn't easy. It was very hard,. [2.8s]

Tolliver: They had two practices a day, two hours each, in the summer heat. After the morning practice, they’d have some down time to eat lunch and rest before the afternoon session.

Tolliver [00:49:27]So you weren't you weren't like hanging out with anyone in between practices? [2.5s]

Gary [00:49:30]No. [0.0s]

Tolliver [00:49:31]No one came to you. [0.8s]

Gary [00:49:32]No one came to me. No. [0.9s]

Tolliver [00:49:42]They all knew each other. There's kind of like morning practice and you get your lunch, everyone scatters, you’re alone. Was that hard? [7.4s]

Gary [00:49:50]Yes, very hard. I didn't know anybody. [2.3s]

Tolliver: And to make matters tenser, my dad was an incredibly good athlete. And fast.

Gary [00:50:49]There was this one guy that everybody was talking about, and his name was John Funkhouser, I remember. [13.5s]

[00:51:03]Yeah, that was the thing because everyone's like everyone's like Funkhouser is fast Funkhouser is the fastest guy on this team. And we're going to match you up with Funkhouser in the 40 yard dash. [13.7s]

[AMBIENCE]

Gary [00:53:12]When we started, we were head to head at about the same speed for about the first. 20, 20 yards, 25 yards, it was pretty even, and then I started to pull away a little bit and Funkhouser couldn't catch me and all of a sudden I got down there and I I think my time was less than five seconds. And and Funkhouser was just amazed that someone was faster than he was [33.8s]

Tolliver [00:54:17]Did you feel a little bit more included after that or was it just kind of like it happened and then everyone moved on? [5.7s]

Gary [00:54:23]No, I don't feel any more included at all. If anything, I probably felt a little more alienated from their life then. [8.3s]

Tolliver [00:54:31]They didn't like that. [0.8s]

Gary [00:54:32]They didn't like that I was faster than Funkhouser. [0.0s]

Tolliver [01:00:59]Were you like, I just wanna go home? Did you not? Like it? 2.2s]

Gary [01:01:02]I wanted to go home? Yes, I did. I wanted to go home. I wanted to get away from there. I want to go back and hang out with Michael and Michelle. [6.6s]

Tolliver: He did go back home, but only for a few days before the school year officially began.

Luckily, though, because he was needing a bit of a break, my dad was a day student and didn’t live on campus. His grandfather would drive him to Woodberry at 6:30 every morning before he left for work, and my dad would stay in the library until classes began at 9.

It was also comforting that there were finally other Black students on campus, with seven others integrating with my father.

Gary [01:40:06]I don't remember where I met Wayne Booker, but I think I met him at the football field because he was on the JV team and that's when I met him, I think. And then we got to be really close friends.

Tolliver [01:40:46]So he was like your first friend once school started and then ultimately your best friend. [5.5s]

Gary [01:40:53]Exactly. [0.0s]

Tolliver: Unlike my dad, Wayne wasn’t a day-student. He lived on campus and didn’t get the same kind of break my dad did in going home at night.

Wayne [00:32:45One of the things that we had to do at Woodberry we had to wait tables. So that was something that all all boys had to do. That was a part of your learning. So when we had sit down dinners at night, you had to be the waiter. You would come in early, you would eat, and then you would set up a table, you would bring food to it. If they ever needed additional food, you had to go get it. You had to clean the table off.

Tolliver: One night, Wayne was on table waiting duty with two white boys…

Gary [01:41:49] I call them the Peterson twins, and they were just awful.

Gary [01:44:51] They walked around like they own the school and they really didn't. They weren't friendly at all. They could care in the least about you being a black kid. [25.2s]

Tolliver: The rule was: if your table was empty, you didn’t have to serve anyone. You could pick a different table and be seated for dinner. Wayne’s table was empty.

Wayne [00:32:45 Harrison Straley was my adviser, and so I went to sit with Harrison. Well, one of the Petersen boys was the waiter of Harrison Straley Table. And it seems like every time something ran out, it ran out at me and I was telling the Peterson boy, go get this, go get that. and of course, him being from Georgia. I'm sure his upbringing was not to have a little black boy tell a white boy what to do. So they stopped me that night and very forcefully said, don't ever sit at a table where either I or my brother are waiting again.

Tolliver: And this certainly wasn’t the only incident.

[MUSIC]

Gary [01:45:25]And I came to school one day because, you know, I'm off campus. And I found out that there was a big ruckus the night before. And I'm like, what the heck went on? And so I was talking to Wayne Booker and he said, well...

Wayne [00:36:49] Well, they would have these musical groups that would come to school and perform. One of the first all black musical groups that showed up. Well, the white students got up and started. You know, they they they march down one of aisles, March across the front, march out the back, and, you know, they were it was like they had their hands on their own shoulders and they were dancing and they were doing this. And we thought very disrespectful to any musical group, specifically the first black group that's ever been there. [51.0s]

[00:37:41]So as a result of this, the black students, we kind of assemble ourselves at one of the back doors and we kind of figured out that the last guy coming in the door, we will we will go. Whoever he was will have a problem. And so it happened and we had an altercation.

Gary [01:45:25] and he said, Raymond Maxwell, which was another one of the black kids, got into a big fight with the Petersen boys. He said, yeah, the Petersen boys called him the N-word. And they got into it. And he said that Maxwell went and got a butter knife and he was going to go cut the Peterson boys. [56.4s]

Gary [01:46:27]Somebody broke it up and Ray Maxwell got in a real big trouble. [4.0s]

Tolliver [01:46:32]Did they get into trouble? The twins? [1.2s]

Gary [01:46:34]I don't remember them getting in trouble. I know that Maxwell got into trouble, they were going to expel him. [6.7s]

Gary [01:46:43]And Maxwell didn't get expelled, but Maxwell didn't come back the next year. [6.3s]

Wayne [00:38:54]And the crazy thing about it, the music that the group was playing was was Led Zeppelin. It was hard rock music. It was not soul music. [54.0s]

Tolliver: Woodberry students were also required to attend chapel, which was very different from Wayne and my dad’s religious upbringings.

[MUSIC]

Gary [00:10:41] I'd been used to having lively choirs and ministers that would speak from a very intense and. Very animated approach to preaching and this preaching or not really preaching, it was more lecturing and talking about things which was different for me.

Wayne [00:10:18] Well, my my religious experience, my parents were members of the Pentecostal church, the Holiness Church, right off the bat, going from a holiness church to Woodberry. Woodberry was Episcopalian. So those two, they don't have much in common. it was very foreign to me, I had no clue what they were doing. I didn't understand the preacher. I didn't understand the services. I didn't understand why they were doing all the stuff. I didn't understand why people were marching up and down with the little flags and everything. It was it was beyond me, but it was something that I grew accustomed to because that was a part of the Woodberry experience.

Gary [00:11:52] I also. Decided that I would take one of the religious courses that Woodberry offered because I thought that was a good way to expand my knowledge around religion, around the areas that I had not experienced before. And the teacher was Reverend Barton Barton, and he was a really nice guy.. He was really impressed with how well I knew the different books in the Bibles because I had grown up reciting a lot of scripture at my home church. He felt as though I could become a great minister and I didn't think that much of that. I I had learned in my life and through my religious and back in my Baptist background is that you have to be called in order to be a minister. And and I certainly had not been called and in a sense to be a minister. [120.2s]

Gary [00:14:54] I thought it was strange, but I thought it was different and something I had never experienced before and made me kind of yearn for going back to my Baptist way of doing things because I felt that that was the way to really. Really, commune was the Baptist way. [32.4s]

Gary [00:15:35] And I was lucky because I was a day student. So I got to go back to my Baptist church every Sunday. And the guys that were on campus didn't get that same appreciation. But because a lot of the maintenance men and the staff were African-American, a lot of them took the African-American students under their wing and would invite them out on Sundays to go to church with them and to have dinner with them and even sometimes watch football and things with them so they could really have somebody they related to be around them [73.3s]

Wayne [00:10:18] Thankfully, a guy named Ed Dorsey who was the head of the custodial crew, a big, jovial fella, he kind of took me under his wings and kind of adopted me so So quite frequently he would invite me to church with him is a Baptist church, was the name of his church, and he would pick me up like ten o'clock. We would go to church, and then we'd come back to his house and watch TV, watch football games or watch whatever. His wife would have dinner fixed and we would just hang out until six or seven o'clock in the afternoon whenever it was time for me to get back to Woodberry. And that was a comforting experience for me because that was more familiar to me than the Episcopal Services or the services that went on at Woodberry. [145.2s]

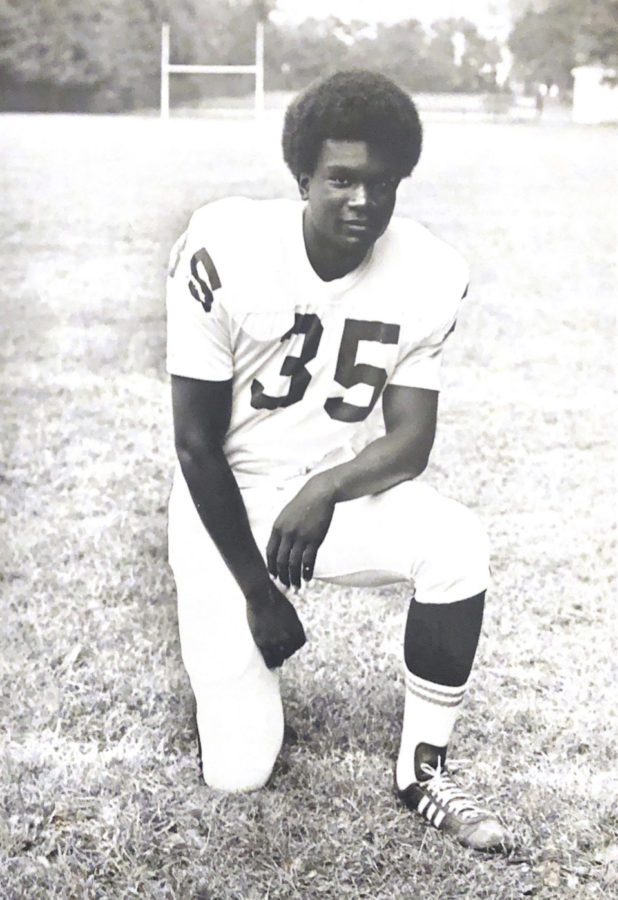

Tolliver: Wayne and my dad were also on the football team. They quickly became stars of the team, and were even considered for the role of captains, which caused problems.

Gary [01:48:22] I think this was my sophomore year, my fourth one year I was running through the football line And one of the white kids came up and gave me a forearm shiver to my neck as I'm running through the line. And it really messed up my neck. I couldn't play football for about two or three weeks because they thought that Wayne Booker and I were getting too much attention and we were going to be the captains of the team or something. [94.4s]

Tolliver: There was one white teacher at Woodberry who supported Wayne and my dad.

Gary [01:29:18]Now Mr. Straley was the coolest teacher as there was. He is undoubtedly a big reason why I excelled and why I stayed at Woodberry, because he was a really cool guy…he really interacted well with black kids And sometimes he would take us to like to Charlottesville to go to movie or go bowling in Charlottesville and go eat out in Charlottesville. And that was huge. Yeah. I never I never had eaten out anywhere. [76.9s]

Tolliver [01:31:29]Could you at this point, could you go into a restaurant with them at that point? [4.3s]

Gary [01:31:34]At that point I could, yes. [0.4s]

Tolliver [01:31:35]Had you never really been in a restaurant where you could go in and sit down and eat with white people? [5.3s]

Gary [01:31:41]No, never. [0.5s]

Gary [01:32:26]I mean, Wayne Booker my Best friend he was advising too, and he liked him just as much and did things with him…

Wayne [00:55:48]You know, we would do things with Chuck Straley like he was our dad. And he was he was a really nice guy. [40.6s]

Tolliver: So, Black students found ways to try to survive and adapt. After ninth grade, my dad felt like things were getting much easier. By tenth and eleventh grade, he developed the study habits he needed to succeed. He got a job in the school bookstore. And he lettered in football and track.

[AMBIENCE]

Gary [00:52:58]Well senior year that was probably my best year. Sports, of course, being much older, being on the football team for four years. And, um, when you're a senior on the football team, when you take the football picture, you get to be on the front row. So Wayne Booker and I were together on the front row. Um, the coach expected more out of us and we got to play a lot more. And having an undefeated season certainly didn't hurt. And it'd been years, many years since they'd been an undefeated football team at Woodberry. [54.7s]

Tolliver [00:22:48]So this is what I have hanging in my room, and it's from the daily progress of the local newspaper in Charlottesville, Virginia, and this is their Wednesday afternoon paper on September 13th. Nineteen seventy two. So on the left, we have Wayne Booker. He's the tailback and there are two other players on the ground and he's jumping over them and says he's jumping over Mark Armstrong, the center, and Tom Cox the tackle. And then on the right, a solo shot. And of you, you can jump in in the air. [45.0s]

Tolliver [00:23:48]so halfback Gary Mance has the potential. [3.0s] [00:24:07]Woodberry Forest head coach will once again try to field a championship squad for the upcoming nineteen seventy two season in hopes of keeping his winning tradition at Woodberry course he feels confident in his material and things look go for the Tigers in the Virginia Prep League. [17.3s]

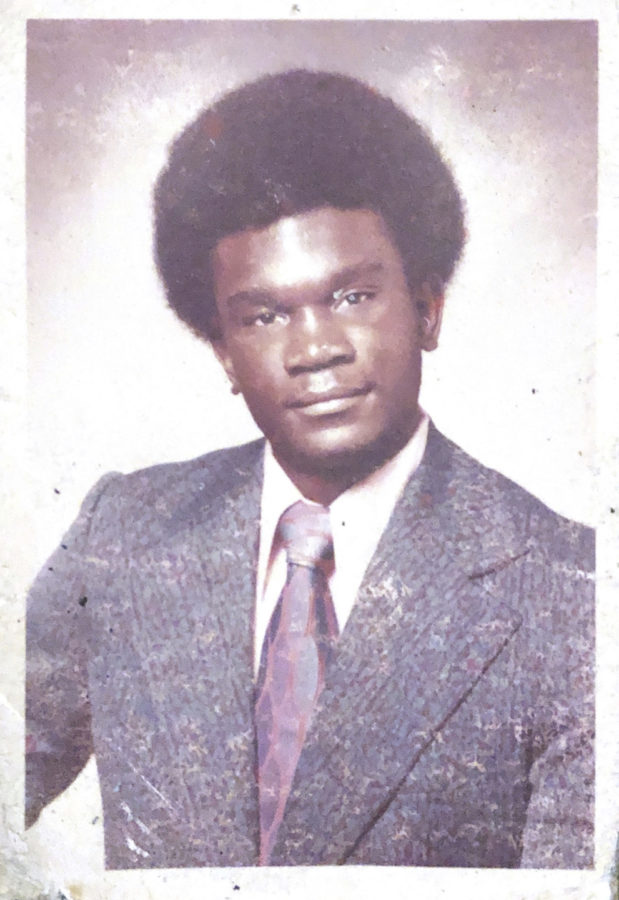

Tolliver: My dad took me through his yearbooks, showing me his sports pictures and his senior picture.

Tolliver [00:46:35]Look at Gary Mance, look at Gary Mance, I had my first look at your fro. [5.4s]

[00:46:42]You're wearing tight pants. [0.8s]

Tolliver [00:46:55]Your quote is [0.6s] [00:47:07]I may not be, but I'm sho going to wait and see, [2.8s]

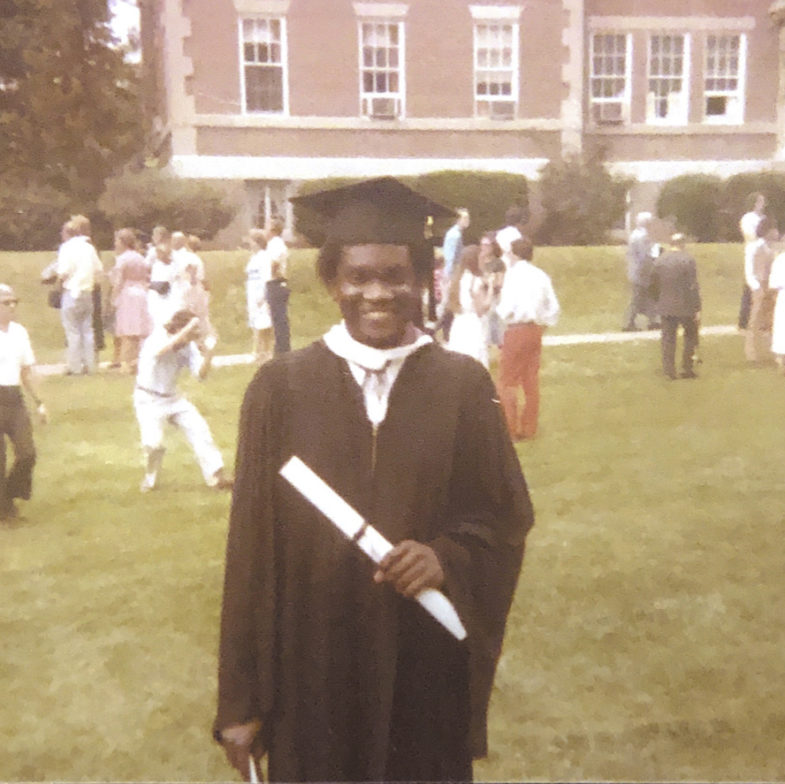

Tolliver: My dad kept that mentality as he graduated from Woodberry. He applied to three colleges and ended up studying Psychology at Washington College.

The life everyone had promised him quickly began to take shape, and it would be 30 years before he returned to Woodberry, for a celebration of the integration of the school. While he was there, he spoke to the headmaster and was invited to the advisory board. From there, he joined the Board of Trustees.

Gary [01:09:01]It felt really sort of strange to be back in that capacity. I never thought that I would be on the board of trustees. I never thought of that as even an option for me. And I wasn't the first black student to be on the board of trustees, but I was one of the first three or four to be on the board of trustees. [34.0s] [01:09:54]I got a chance to meet the minority students that were there and to really see a difference in school where when I was there, there were only eight of us in that first class and now there were about 40 different minority students. And they weren't just black students. They were black, Latino, Asian. So it felt a lot different. [38.1s]

Tolliver [01:10:35]Did you realize now at that point that that was directly as a result of what you did? [4.9s]

Gary [01:10:41]Yes, without a doubt. I knew now that it was a direct relationship to what I did, even to the point where some of the black students that I met after I got back into the school again would come up and tell me how much they appreciated what I did in order for them to be a student there now. [30.5s]

Tolliver: My father is certainly an optimist in every sense of the word. He learned from his grandparents, who despite being born in the 1920s and living at the height of Jim Crow in Virginia, believed wholeheartedly that a better world was possible for him. But now, in 2020, with his own children, my dad still sees democracy fail Black people every step of the way.

[01:13:42]I tell you, it's very difficult when I look back and have introspection about things. Yeah, there are people that have come to me of the white race or whatever and talk about how far we've come. I don't see as much progress as they do. I, I know that, yeah, some people may treat me differently, but there's still a lot of people that still treat me pretty much like they did back in the 70s. And, um. I find that when me as a as a black man, when I begin to aspire to higher and higher levels, that some white people look at me as taking over for what they can or can't do now because I'm doing it even in the business world that I'm a part of. It's interesting that while not so much interesting as it's prevalent that people don't perceive me for what I am when I go out in public with my team and I'm the leader of the team and the people that report to me are mostly white individuals. It's funny how maybe you go to a restaurant or to an event. People will not recognize me as a leader of the group. They will come to a white person to see if they're the leader of the group. So that happens even today. So there's still so much further that we have to go and. [134.3s]

[01:16:06]you know, I've always thought that by the time that I got to the age that I am now, that there would be so many more differences than what I felt when I was growing up. And now I can only hope that by the time that my children get to this age that they will see the differences. Because I honestly think that the key to change is it's got to start with the parents and how they raise their children, and that will then change the world. [39.8s]

Tolliver Mance

Tolliver Mance