A Look at Recognition

By Caleb Hendrickson

After centuries of disenfranchisement and a demanding application process, the Pamunkey tribe of eastern Virginia received federal recognition in 2016. Federal recognition is a landmark achievement for the tribe. However, a greater recognition is yet to be realized.

In her 2017 dissertation, Ashley Spivey, anthropologist and former director of the Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center, relates an interaction with a visitor to the museum. The visitor wished to see “real” Indians on the Pamunkey reservation. “Where are the Indians?” the visitor asked an employee. “They’re probably at work,” she was told.[1] Non-native people often imagine the Pamunkey and other native people of Virginia as relics of the seventeenth century rather than citizens of a modern society. Presumably what makes an Indian “real” is to be from another time. However, as this interaction shows, “real Indians” are also expected to be on view in the present, visible on demand. In short, Native Americans are imagined to be past and present at once.

Such an expectation rests on mutually contradictory beliefs about when Native Americans exist. Non-native perceptions of native people are defined by a multitude of such mutually contradictory beliefs. According to a recent public opinion study many Americans perceive native people as “both savage warriors and noble savages” who “live in abject poverty on reservations, yet are flush with casino money.”[2] This accommodation of totally contradictory qualities is a hallmark of ideological imagination. Think of familiar antisemitic tropes: Jews are both capitalists and communists, rigidly legalistic and morally decadent, nationalistic and cosmopolitan.[3] An equally outrageous and destructive form of ideology has facilitated the dispossession of Native Americans in the United States — the dispossession of lives, lands, languages, and cultural memory. Features of this ideology continue to shape perceptions of native people today.

John White, Secotan Warrior of North Carolina, 1585, watercolor.

An ideology presumes an image. The American image of “the Indian” has deep roots in the religious imagination of the colonial era. In the Pamunkey Museum you can see a picture of what the English artist and colonist John White took to be a “real” Indian. White depicts his subject, a Secotan man, in the style of high European portraiture: standing in contrapposto, his figure molded in the fashion of Renaissance sculpture. To English eyes, the native physique approached a classically-inspired European ideal. John Smith, settler of Jamestown, described a Susquehannock man as “the goodliest man that ever we beheld.”[4] His description was typical. Smith and White paint pictures of an American Adam. The Indian appears to them as man in his natural state, who—because unfallen—is imagined to inhabit a higher stage of spiritual development. “Colonial accounts of native bodies carried implications beyond mere physical descriptions,” writes Edward Bond, “for English philosophy and theology linked body and spirit by suggesting that the exterior appearance of the body provided evidence of the interior state of the soul.”[5] The fair proportions of the native body, according to White’s and Smith’s depictions, correspond to a perception of the native soul as pure and untouched — a near perfect preservation of the imago Dei in which all human beings are made, according to Christian belief.

However, the image changes when viewed from a closely adjacent point of view. According to the same English theological imagination, the New World was Satan’s “ancient freehold,” its inhabitants Satan’s chattel. The obligation to liberate North Americans from Satan’s power provided the principal theological justification for conquest. From this vantage point, Smith does not see an American Adam in whom the imago Dei has been miraculously preserved. Rather, he sees something closer to Jean Calvin’s image of “natural man,” “so depraved [in] his nature that he can be moved or impelled only to evil.”[6] Smith found evidence of the soul’s disfiguration in the tattoos, paint, and ornaments adorning native bodies. Thus, while a moment ago a Susquehannock man appeared to Smith “as the goodliest man that ever we beheld,” a Powhatan man now appears to him “more like a devil then a man, with some two hundred more as blacke as himself.”[7]

English vision was fully capable of these mutually contradictory perceptions. To the colonist’s eye, the native North American became the site (and the sight) of a fantastic coincidentia oppositorum laden with theological import. Smith gives this coincidence of opposites a concise formulation: “he is the most gallant who is the most monstrous to behold.”[8] Representations of Native Americans in modern culture often replicate Smith’s double-vision. When it comes to picturing “the Indian,” he is the most gallant who is the most monstrous to behold. It is not necessary to enumerate here the countless instances of the noble savage and the savage barbarian juxtaposed in literature and on screen.

The point is that these pictures are the projections of a colonial eye. They are the negatives from which a certain self-image of the Euro-American are to be developed. “Greeks always require barbarians,” writes Edward Said.[9] So, too, do Americans. “No Greek will be able to discriminate my body,” writes the twentieth century poet Charles Olson, for “An American / is a complex of occasions.”[10] For Olson, this “complex of occasions” is “of a spatial nature.” It is a geographical space, in resistance to which the self has its being. For Olson, “the Indian” remains part of that natural geography, and continues to serve as a reflecting pool of the non-native ego, “by the way into the woods / Indian otter/ orient / “Lake” ponds / show me (exhibit / myself).”[11] These fantastical projections have obstructed our view—as a nation and a culture—of the realities that shape life on this continent, and especially the lives of native people. They have facilitated a profound misrecognition of Native American history and identity.

But, how does a culture and a nation recognize people it has colonized? There are many ways to answer this question politically: projects of reconciliation, repatriation of remains and artifacts, the granting of land rights, constitutional amendments, and social, political, and material entitlements to native groups. On the other hand, many contemporary activists and scholars, such as the indigenous scholars Glen Coulthard and Audra Simpson, reject the politics of recognition altogether.[12] They argue that the quest for recognition does more to reproduce the effects of colonialism than ameliorate them. These voices challenge hierarchical models for conceiving and talking about recognition, especially models that give the state recognizing agency. They emphasize the power of refusal over recognition, and the power of solidarity between subaltern groups.

Whether greater democratic freedom lies with a politics of recognition or a politics of refusal, the political is sure to be accompanied by pictures. We must learn to see these pictures as they appear. And, as always, artists may be our instructors in vision.

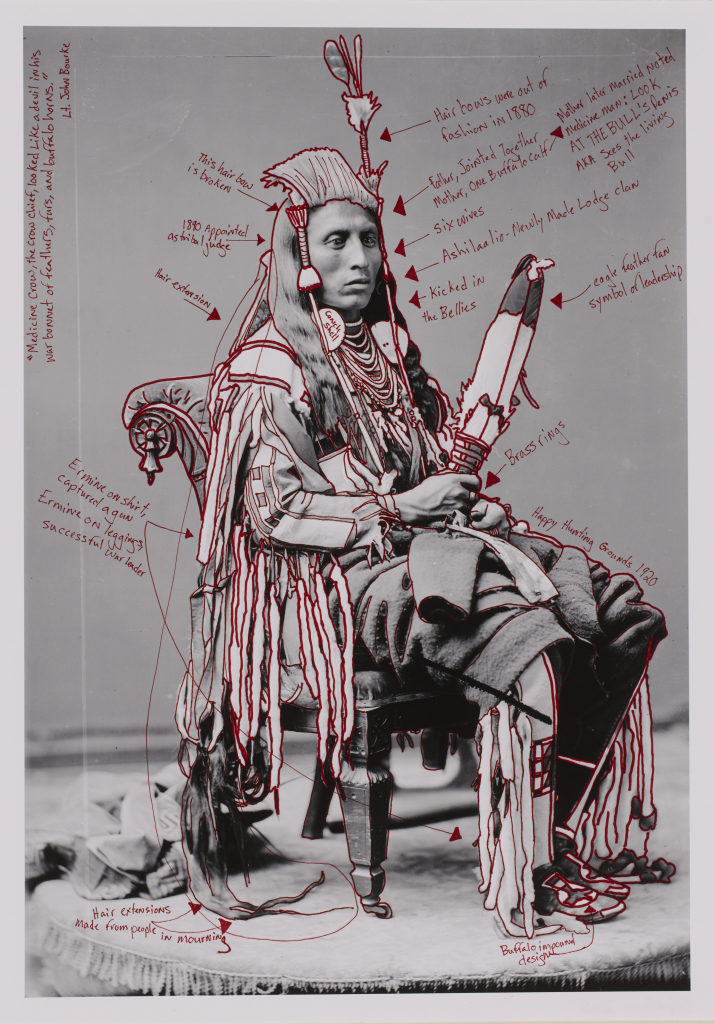

In a series titled Medicine Crow & The 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, Crow artist Wendy Red Star annotates photographs of Crow leaders who traveled to Washington D.C to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes. In Peelatchi-waaxpáash (Medicine Crow), Red Star scrawls details of the Crow chief’s life: “Father, Jointed Together; mother, One Buffalo Calf,” “1890 appointed as tribal judge.” She carefully traces the outline of Medicine Crow’s wardrobe and identifies its components, sometime explaining their significance: “Brass rings,” “eagle feather for symbol of leadership,” “conch shell.” Along the left hand side of the photograph, she quotes Lt. John Bourke, an army captain who reported on the summit between President Hayes and the Crow delegation. “Medicine Crow, the Crow chief, looked like a devil in his war-bonnet of feathers, fur, and buffalo horns,” Bourke writes. Bourke repeats Smith’s equation of native attire with devilry. Red Star’s notations serve not so much as a refutation of this trope as an exhortation to look, to see the photograph not as the symbol of theologically heightened reality (a damned ideology), but as the trace of a person with a history—as complex and mundane as anyone’s.

Wendy Red Star, Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven), part of the series, 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014, artist-manipulated digitally reproduced photograph by Charles Milton Bell, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, pigment print on archival photo-paper, 24” x 16.45” with additional 1” border

How difficult it is, how necessary, to become aware of how we look, then to look again, perhaps even to see.

[1] Reported in Spivey, “Knowing the River, Working the Land, and Digging for Clay: Pamunkey Indian Subsistence Practices and the Market Economy 1800-1900,” PhD Dissertation, College of William and Mary, 2017, 315.

[2] Reclaiming Native Truth, a two-year public opinion survey conducted by the First Nations Development Institute and Echo Hawk Consulting. On contradictory stereotypes see, “Research Findings: Compilation of All Research,” 2018, 11.

[3] On the contradictoriness of antisemitic stereotypes see Michael Curtis, Antisemitism in the Contemporary World (Boulder: Westview Press, 1986), 4. Consider also Jean-Paul Sartre’s remark: “The anti-Semite readily admits that the Jew is intelligent and hard-working; he will even confess himself inferior in these respects. This confession costs him nothing . . .the more virtues the Jew has the more dangerous he will be,” quoted in Gertrude Jaeger Selznick and Stephen Steinberg, The Tenacity of Prejudice: Anti-Semitism in Contemporary America (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 5.

[4] Quoted in Karen Ordahl Kupperman, Settling with the Indians: The Meeting of English and Indian Cultures in America, 1580-1640 (Rowman and Littlefield, 1980), 37.

[5] Edward L. Bond, “Source of Knowledge, Source of Power: The Supernatural World of English Virginia, 1607-1624,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 108, no. 2 (2000): 119.

[6] Jean Calvin, Institutes II.3.5 (1539). Calvin’s Institutes: A New Compend (Westminster John Knox Press, 1989), ed. Hugh T. Kerr, using John Allen’s translation, 61.

[7] John Smith, The General Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles … (London, 1624), reprinted in Philip L. Barbour, ed., Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580-1631) (3 vols.; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1986), 2:151.

[8] Smith, General Historie in Complete Works, 2:161.

[9] Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism, 25447th edition (New York: Vintage, 1994), 52.

[10] Charles Olson, “Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [Withheld],” The Maximus Poems (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 185.

[11] Olson, “Maximus, March 1961 – 2,” The Maximus Poems, 203. On Olson’s image of American Indians see Michael Castro, Interpreting the Indian: Twentieth-Century Poets and the Native American (Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983), 99-114.

[12] See Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), and Samantha Balaton-Chrimes and Victoria Stead, “Recognition, Power and Coloniality,” Postcolonial Studies 20, no. 1 (January 2, 2017): 1–17.

Additional Reading

Bond, Edward L. “Source of Knowledge, Source of Power: The Supernatural World of English Virginia, 1607-1624.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 108, no. 2 (2000): 105–38.

Castro, Michael. Interpreting the Indian: Twentieth-Century Poets and the Native American. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983.

Coulthard, Glen Sean. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Settling with the Indians: The Meeting of English and Indian Cultures in America, 1580-1640. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980.

Reclaiming Native Truth. Research Findings: Compilation of All Research. First Nations Development Institute, 2018. Available: https://www.firstnations.org/publications/compilation-of-all-research-from-the-reclaiming-native-truth-project/

Simpson, Audra. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

Spivey, Ashley Atkins. “Knowing the River, Working the Land, and Digging for Clay: Pamunkey Indian Subsistence Practices and the Market Economy 1800-1900.” PhD Dissertation, College of William and Mary, 2017.

Related Project

Get Involved

Learn about forthcoming podcast episodes, newly published projects, research opportunities, public events, and more.

Potential Students