There was something grotesque about what I was doing; I knew that my grandmother – Savta as we say in Hebrew – had survived the Holocaust. And yet, clicking through the Yad Vashem Database of Shoah Victims, I couldn’t help but feel a pang of disappointment when I typed in Savta’s name and nothing came back. While Savta was, of course, one of the many victimized by the Shoah, it was because she was not on that list that I could even exist to look her up in the first place. The disappointment, then, was not about the circumstances of getting on the list but about being on the list at all. The Holocaust is, for many of its survivors and their descendants, a matter of uncertainty. So many things – so many people – have been lost to history. I had hoped, having spent several months circling the gaps in Savta’s biography, to stumble upon the key to her memory in that list. But she wasn’t there. Losing interest, I typed in as many combinations as I could think of that might bring her out: her first name plus her hometown, her last name plus the nearest city, her father’s first name, her mother’s maiden name…

I stared at the screen.

Hana Handelsman Nusbaum.

In front of me, undeniably, was my grandmother’s name, shining in blue. Blue, as in a hyperlink. Blue, as in there was more.

Click.

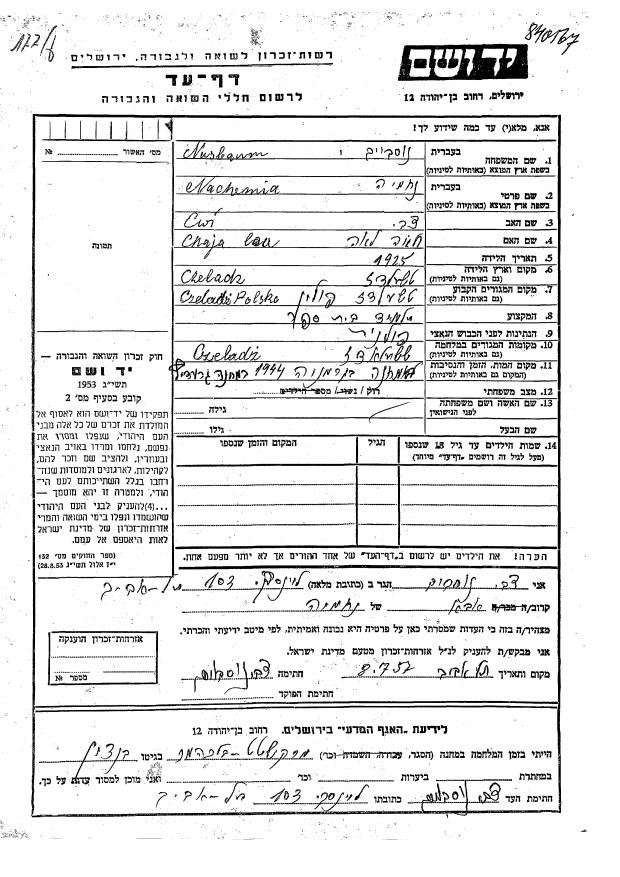

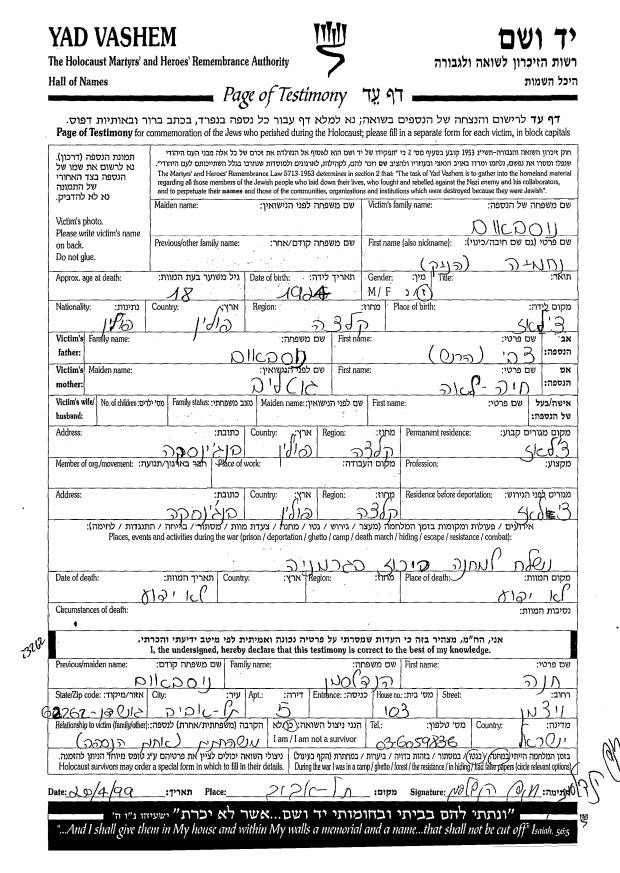

What I found was not, as I initially thought, an account of Savta’s life. She was listed not as a victim but as a submitter: unfolding beneath her name were 26 entries. Handelsmans, Nusbaums, and more. Family members; forms she had submitted on their behalf. Twenty-six people she had known and loved who were taken from her. Murdered. She had given testimony of their lives.

If this project has a genesis, it would be that moment. Looking through the forms, I realized Savta had actually filled them out twice: once in 1957 and again in 1999. While perhaps unusual, in and of itself these double testimonies were not awfully significant; most of them were filled out in exactly the same way. But there was one that was different: that of her brother, Henik.

If this project has a genesis, it would be that moment. Looking through the forms, I realized Savta had actually filled them out twice: once in 1957 and again in 1999. While perhaps unusual, in and of itself these double testimonies were not awfully significant; most of them were filled out in exactly the same way. But there was one that was different: that of her brother, Henik.

Savta always said there was no wisdom to surviving; it was simply fate. Nevertheless, by her account, she never would have survived if it had not been for her brother. When their father was taken away, Henik worked to feed the three of them. Eventually he managed to get a work permit for Savta, a work permit that, when the Nazis rounded up everyone in the ghetto, meant that she was going to go with the other laborers instead of with the rest of the women (all of whom, including her mother, were sent to Auschwitz, and never heard from again). Savta has dozens of stories like this about her brother.

I was surprised, then, looking through these testimonies, that Savta said she did not know where or how her brother died. I had just finished reading her autobiography, in which she states exactly when, where, and how it happened. Looking back through the documents I realized that when she first filled out the forms, in 1957, she had also stated how he had been killed. Why, then, did she say she didn’t know in 1999? She had not forgotten, or else her autobiography, written in 2015, would have contained the same gap. Why did that memory, and only that memory, temporarily disappear?

Answering that question was what moved me to start this project. My plan was to sit down with my grandmother and interview her about her experiences, about her brother, and about that elusive memory. That was easier said than done. Savta and I live 6000 miles apart and, between her inconsistent health, Covid, and many other limitations, I was never able even to attempt that conversation. Most of all—and the reason why the project has always been somewhat of a race against the clock, for the past few years Savta has been struggling with dementia. Sometimes she knows who I am; sometimes she doesn’t. Sometimes she gets frustrated because she doesn’t entirely know who she is. Imagine, in that context, asking her why she misremembered something over 20 years ago.

The project thus became not just about Savta and her memories, but about how my family remembers her and the collective history she embodies. This film is not about telling a Holocaust story – it would take weeks to tell just half of my grandmother’s experiences – but about untangling our complex relationships with memory. It is a film about the necessity of both remembrance and forgetting.

Sometimes we must remember precisely so that others may forget.

Additional Reading

Halbwachs, Maurice. On Collective Memory. 1925. Edited and Translated by Lewis A. Coser. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Novick, Peter. The Holocaust in American Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999.

Ozick, Cynthia. The Shawl. New York: Vintage International, 1980.

Additional Credits

I am deeply indebted to the Religion, Race & Democracy Lab, Light House Studio, and UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art for their support during this project, and in particular to Emily Gadek, Will Goss, Kelly Jones, and Prof. Caroline Rody for their insightful feedback. In addition, I am thankful that the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum allowed me to use footage from their collections in this project; similarly, I am grateful to have discovered and been able to include breathtaking music by Fjodor. I could never have finished this without the help of my family, who were kind enough to not only appear in this documentary, but also to take on roles behind the camera. Most of all, thank you Savta: for your laughter, your love, and your kneidlach. Ze ma yesh.

Get Involved

Learn about forthcoming podcast episodes, newly published projects, research opportunities, public events, and more.

Potential Students