Speaking in Sharpe Tongues: Kamau Brathwaite, Margaret Gill, and the Sound of Black Power

You probably have the lights on right now, but I want to take you to a huge city without power. In Kingston, the capital of the Caribbean island of Jamaica, blackouts are part of daily life. There are no sources of fossil fuel on the island. Power outages are inevitable. One day in 1982, the problem of power hit a historian.

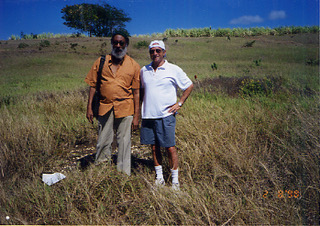

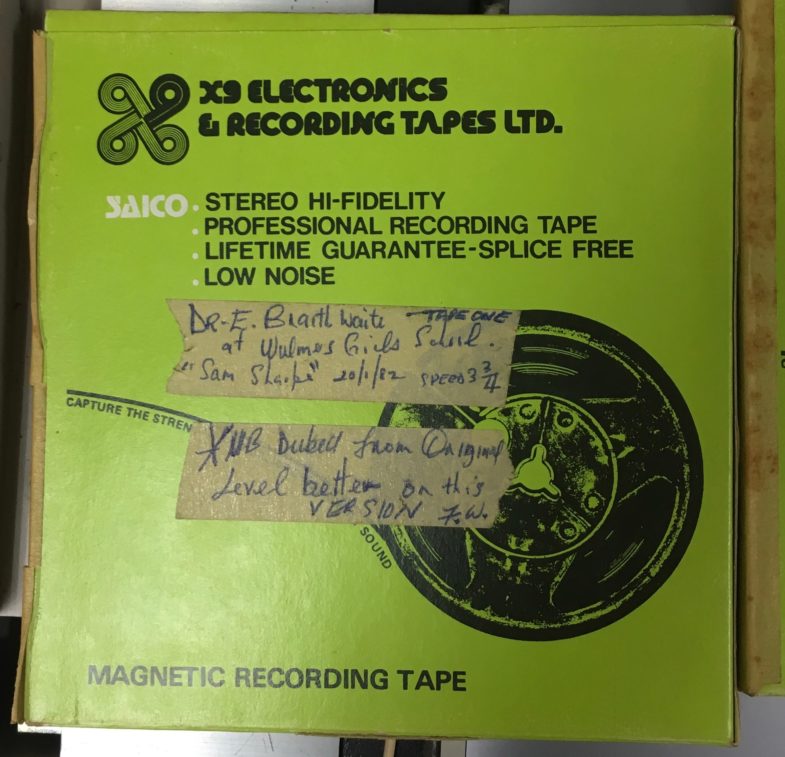

A blackout almost prevented a lecture by Kamau Brathwaite, an esteemed poet and historian from Barbados. The organizers scrambled to relocate. But the best venue they could find was a local girl’s school. People still came. Against the rumble of a generator and surrounded by growing dusk, Kamau’s subject was almost too perfect: it was power. Black power. He was teaching his listeners about the leader of the most successful revolt of enslaved laborers in colonial Jamaica. That man’s name was Sam Sharpe. His revolt led to the end of slavery in the British empire.

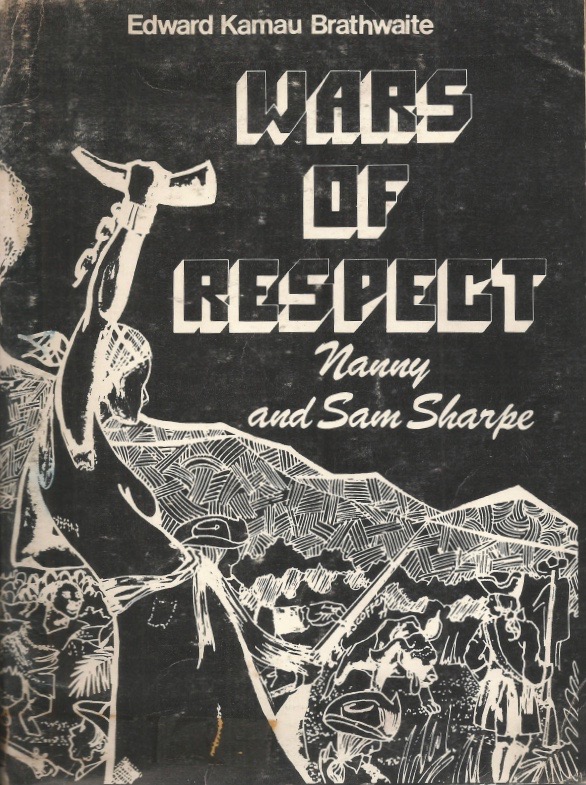

Today there’s no shortage of books about these sorts of uprisings. So you may have heard of Sharpe’s. It’s often called the Christmas Rebellion or the Baptist War. (It began in a Baptist community in December.) But at the time Kamau was writing, not much was said about figures like Sharpe. Even less was said about Sam Sharpe as a genius of resistance. Those subjects were threatening. The government responsible for power outages was also aggressively silencing radical Black leaders. (A prominent historian of Africa and Black Power activist, Walter Rodney, was expelled from Jamaica. And he was assassinated a few years before Kamau delivered his Sharpe lecture. They were friends.)

The suppression of Black leaders wasn’t just a governmental problem. It was baked into histories of the Caribbean. So studies of revolt were eyed with suspicion. And they tended to be one sided. They had plantation owners as all powerful and the enslaved as victims.

“Let me draw your attention to something which white universities and white libraries practice.”

Walter Rodney called historians out for this out a few years before his death . . .

“Go into their libraries and check the Library of Congress Cards. There are no entries on the Africans overseas. There is no such category. Africans who have been ripped from the continent, mysteriously disappear and become negroes.”

Historians had built their opinions of Sam Sharpe on archival records composed by white power. Even though those records erased and skewed evidence. In them, Black leaders were feared. They were also imitators, incompetents. And they mysteriously disappeared.

“Very few of us really know, know, that slaves, Blacks, no things, nums, a hundred and fifty years ago were really capable of so sharply contributing to the world revolution of man, which was then sweeping the western world.”

This is Kamau summarizing the situation on January 20, 1982. It was 150 years after Sam Sharpe was hung just after Christmas and the rebellion ended.

“In the newspapers constantly when people discuss the slave rebellions, you see that they are basing it on no information. And in fact, they probably claim that there is no information despite the research being done.”

But Kamau was in the middle of a sea change in histories of enslavement. It was an exciting time. Archeologists were excavating burial grounds of enslaved Africans and identifying key locations of revolts. Historians were scouring untouched archives. Novelists were imagining new ways of approaching the past. As a poet, not just a historian, Kamau’s contribution was unique. He also wanted to recover the sound of revolt. If we can’t see it in the archives, can we hear it? What is it like to speak like Sam Sharpe?

There would have been a more basic question on everyone’s mind that evening as they listened to Kamau speak. What is it like to lose power? The audience probably remembered when the lights went out. They couldn’t see. They relied on other senses, on feeling, hearing.

Kamau engaged that experience in his talk. He called on his listeners to imagine sounds:

“Now before that though, I’ll give you an idea of how documents can suddenly reveal things, which one would not expect this afternoon in the middle of a power cut.”

Of how documents can reveal not just objects but soundscapes.

“The drum begins to sound soon after the plots are in place, and when the drum sounds, the name of God is also reverberating.”

The loudest cue of the Sam Sharpe rebellion would have been drumming. In 1831, it was illegal for enslaved Africans to drum. Drumming had cultural and spiritual meaning. Beating drums unified the enslaved. It summoned gods. It was synonymous with power. But the drum didn’t sound alone. Sam Sharpe was actually a Baptist deacon, which is why Kamau imagined Baptist songs merging with drums in the early days of the revolt.

“In those hills, the black deacon could not control this congregations. I mean, if they wanted to start humming and breathing and stompings . . . he was alone with them.”

The talk went on for another hour. It covered a lot of ground. But beneath it all was a study of the intertwining of sounds. Sounds pointed to adaptation and to agency, to Black leaders who didn’t behave quite like the history books wanted them to, who were Baptists and Africans. The blending of sounds was a blending of worlds. Sometimes those sounds adapted to each other in surprising ways. Sometimes they were purely opposed. Rebellion sounded like a lot of things at once.

“The process of Creolization, of adaptation one to the other, is taking place. But this radical movement of being themselves, of being African, is very much there.”

At the end of the day, after the school emptied and everyone left for their dark homes, Kamau didn’t just want to study the Sam Sharpe rebellion. He wanted to reconnect to the history of Black power, in poetry. Doing that wasn’t as simple as reproducing some pure, racialized past. It meant finding sounds for struggle. What if a poem sounded like a rebellion?

“Like most of us who become conscious of all the traditions that have created us, beginning with our mother tongue Bajan, Kamau had to wrestle with several religious schema.”

This is Dr. Margaret Gill, a Barbadian poet and onetime collaborator with Kamau. Writing literature in the Caribbean is like standing inside a hurricane, she told me.

“The metaphor that we can use to talk about our literature is the hurricane. . . . Ok, so the hurricane, at the heart of the hurricane there is a stillness, so you can be still and know that I am God, but trust me, on the backend there is hurricane, on the front end there is hurricane, on all coordinates there are fierce winds blowing. So there has to be a struggle.”

In the Sharpe rebellion, sounds turned on each other. They could also bleed into each other. Drum rhythms erupted alone. But they also merged with hymns. In his poetry, Kamau has us tune our ears to the many kinds of struggle. Here’s an obvious example. In a performance of one of his long poems, he used several speakers. One voiced a slave master, the other an enslaved laborer. The master told the laborer what to say:

Voice one: Say what, say pot, say rot, say rat,

Voice two: O’Grady says

Voice one: Say right, say white, say black, say wrong, say right, say white, say black, say wrong, say right, say white, say black, say wrong.

But you can hear a drum rumbling underneath this scene, too. If you remember that drums were instruments of revolt, you might start to sense a struggle. Overtly the master controls speech. Covertly, the drum masters the master. The poem is restaging a revolt in sound.

Struggles don’t always sound so clean. In the Baptist spaces where the Sam Sharpe rebellion began, sounds mingled. Those crossings are struggles in their own way. We hear them in the many ways of speaking a language, or a word. Like this one, a pun:

“It is called Sam Lord. P S A L M. In addition to S A M.”

Sam Lord is a famous Barbadian pirate. But in some regions of the Caribbean, Sam sounds like Psalm. What follows is a twisted Psalm, a Psalm that migrates between languages and cultures:

The lord is my shepherd

he created my black belly sheep.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures

where the spiders sleep [. . .]

thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies

candle, book of confectionary that I will proudly bear

bell that I will break and pour its sound in the veve

breadfruit: casket of my mother

plantain, mortar, slave song

Kamau’s paraphrasing the 23rd Psalm: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want, he makes me to lie down in green pastures. . . . He prepares a table before me in the presence of my enemies.” I didn’t know what a book of confectionary was (it’s a ritual cake). The same with a veve (it’s a voodoo sign). I had to look them up. There are a lot of powers tugging on each other here. Texts. Rituals. It’s a wrestling match. And the poet is its pirate. Sam is boarding Psalm. And another Sam seems to emerge in the process. The master of struggle, Sam Sharpe.

You’ll often hear Margaret struggling with the sound of a single word, too. With a word like “Mother,” which sounds like “Myrrh,” which sounds like the gift of the Magi to the infant Christ. Listen to her poem, which Kamau actually published in his own book, Liviticus:

Myrrh, Bajan for when your mother vex dem,

like your myrrh, a Jesus thing we all go through

and wish to hell we didn’t have to,

a bitter lead, like Rasta justice,

Myrrh, for trembling at the knees, for peace.

“Well that, that must have been influenced by Kamau ’cause he got it in his book.”

Myrrh is a balm. But it comes with all the complicated feelings we feel toward our mothers. It vexes. It’s bitter. It’s something we go through but wish we didn’t have to. Myrrh is struggle, but myrrh is peace. In the push and pull between meanings you can hear an echo of the rebellion. You can also hear a new resonance. Margaret shows us that struggle isn’t just a clash. Or a blending. It has a future. It just might end in peace.

Kamau Brathwaite passed away during a global pandemic. And Margaret almost didn’t make it to his funeral.

“He had a national funeral, and I was asked to bring a tribute. We had a terrible problem here at the time, traffic was two hours it took me for a thirty-five minute drive to get to the church. And when I got there, and I got in the church, I realized I left the book in the car. So had to make up the tribute that I did right?”

The piece of paper she lost said something about peace beyond struggle. About Kamau’s life as a kind hurricane, or a myrrh. She didn’t get to read it then, but she shared some of it with me:

“Kamau took something ephemeral, something elusive, the mere beauty of everything and nailed it to something material, which was our responsibility to each other and the future. This responsibility lay in the conduct of our relationships with each other and our honest exposing of the past, to the future.”

Speaking in Sharpe’s tongues, as Kamau did, doesn’t just mean revolting. It means changing our relationships to each other and to the past. It means moving between sides. It means spanning fields. It means saying two things at once. Sam Sharpe didn’t have one voice. He had many voices, like a pun, a hurricane, or a god.

Today the former British colonies have many of the same struggles they had in 1982. Power is still a problem. But when Margaret was reading her poem, the image of the hurricane came back to me. In the middle of a struggle, the poem discovered stillness. The tug between Sam Sharpe and white power seemed to lead to a similar clearing. Sharpe was murdered, but he paved the way for the emancipation of almost a million enslaved people. The poets that claim Sharpe as an ancestor imagine similar futures.

“Because if you, if you want the future to exist, you want it to be not like now, because if it’s like now, now is a terrible place.”

As we approach Christmas, the season of the Sharpe rebellion, sand from the Sahara still reaches the Caribbean islands, and the poets still bring their “myrrh, for trembling at the knees, for peace.” And, my conversation with Margaret was postponed after Barbados lost power.