[Music In]

Isaac: I grew up right next to Danbury Connecticut. It’s a pretty small city of about 80,000 people now. Over a century ago Danbury was known as the “hat capital” of the United States, though that industry has long disappeared. It was a fairly boring place to grow up; all the exciting stuff was an hour away, in New York City.

It was only once I was in graduate school that I learned what happened at Danbury Prison during the Second World War. During the conflict, the most extreme objectors to war refused to help the government in any way. They wouldn't work on farms or labor camps to aid the war effort. They would rather go to prison than cooperate. But if the government hopes sending them to prison would silence them. They were wrong. In 1943, a group of 23 predominantly white conscientious objectors, or Cos, staged a prison strike. They were protesting not against war, but against their segregated dining facilities. Some engaged in a work strike, others started a hunger strike. As a result, they were separated from other prisoners in administrative segregation for one hundred and thirty-five days. These were determined guys willing to sacrifice everything for their principles.

Song: When in a correctional clink

They teach you that colored guys stink

Isaac: That’s a cover of a song written by James Peck, an imprisoned activist

Song: We say that this is sham

Must take it on the lam

—Jim Crow must scram.

Isaac: He performed it during the strike on a guitar made mostly out of a mixture of newspaper and ground oatmeal.

Song: World War II Resisters 209

Whenever you go to eat grub

The Negroes you have got to snub

In teaching to hate

They rehabilitate

—Jim Crow must gate.

They say that Hitler is wicked.

Isaac: Eventually the CO’s would manage to win their battle, managing to make Danbury’s prison mess hall the first desegregated dinning facility run by the federal government.. This is nearly fifteen years before events like the Greensboro sit-ins, which led to Woolworth’s department store ending segregationist policies. Here, the tactics that the civil rights movement would use were being pioneered.

What startled me, as someone raised in Danbury, was learning that aspects of prison life at the time had been racially segregated. Growing up in the Northeast, you're taught in school about segregation in the South, but rarely hear anything about it locally. Luckily, I had local sources of my own to turn to for research.

Martha May: My name is Martha May; people also know me as Marcy. I’m a professor of history at Western Connecticut State University. I’m also co-chair of the history department.

Isaac: You’re related to me?

Martha May: Yes, I’m your mother.

Isaac: Having a historian of the 20th century for a mother can be helpful when you’re trying to understand what was going on with a prison in the 1940s.

Martha May: In the depression in the 1930s Danbury is hit very hard, and so New Deal projects like the WPA, or Works Progress Association funding to create a federal prison were very welcomed by the people here. It was constructed as a prison for men, and seen as a kind of state of the art in the 1940s. One of the things that is such an issue for so many New Deal Programs is that there is such caution on the part of the Roosevelt Administration about desegregation of any kind. An so, an overwhelming majority of federal programs treat African-Americans quite differently than they treat white Americans. Historians have argued that it’s Roosevelt’s awareness of his need for the votes of White Southern Democrats in Congress that makes him cautious about any kind of move that might be seen as supportive of racial equality or a challenge to the Jim Crow Segregation that Southerners are insistent on maintaining.

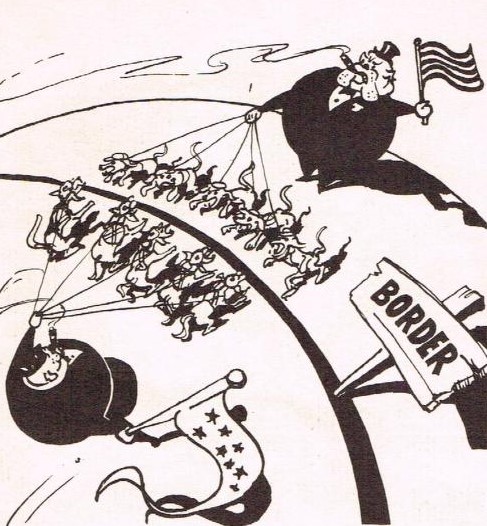

Isaac: With the Roosevelt administration reluctant to challenge segregation, the C.O.s decided to do things themselves. They wanted to force the matter, and their protest was a means of doing that. For the COs, the politics of objecting to war and the politics of objecting to segregation weren’t so different. All politics needed to be held against a standard of divine justice.

McKanan: I’m Dan McKanan, I’m the Emerson Senior Lecturer here at Harvard Divinity School.

Isaac: Dan studies religious activists, like those who protested segregation at Danbury.

McKanan: Within religious tradition you always have some people who are interested in preserving the existing social order, and others who are eager to hold the existing social order up against the standard of divine justice, and to denounce, to call to transformation people who are involved in various kinds of injustice. In the United States progressive religious leaders have spoken out against slavery, they have spoken out against war, they have spoken out against economic exploitation. Any many of the people involved in draft resistance in the World War period drew on all these traditions.

Isaac: Dan says that these various causes mingled together among the Christians that would become COs in the Second World War.

McKanan: In the 1920s and the 1930s ever increasing numbers of social justice-oriented Christians coming to believe that opposition to war went hand and hand with socialism or other approaches to economic justice. So, you had this growing tradition that was making a lot of connections, aware of the connection between economic exploitation and Jim Crow segregation, aware of the challenges faced by African-Americans who were moving into northern cities like New York in the 1920s and concerned with confronting injustice in all its forms.

Isaac: Dan explained how COs, like those at Danbury, saw themselves as engaged in a sort of nonviolent warfare against injustice. Often they had two big inspirations, Gandhi and Jesus.

McKanan: One of the words that had been used historically to describe pacifist action was “nonresistance,” and that word had, was a reference to the New Testament, where Jesus tells his followers not to resist those who oppress them. What Jesus seems to have in mind is a fairly active, creative way of turning the violent assumptions around. To say if someone asks for your cloak to give them your shirt too is clearly not advice to be a doormat and let people walk all over you, it’s advice to creatively transform a situation. But a lot of people heard the word nonresistance and thought it meant being a doormat. Gandhi provided a kind of step-by-step method for being active in the way you resist violence, without resorting to violence yourself. And many of his followers, both in India and the United States, tried to systematize the steps. So you identify an evil, you let the people who are perpetrating that evil know you see what they are doing, you make a specific demand, you give them the opportunity to change their way. Then, if they refuse to change, you engage some internal work of purification, you might do some fasting, you might do some internal reflection, then you take a specific nonviolent action, like a march, like a boycott, in the U.S. context of fighting against Jim Crow segregation, like a sit-in. But these are all part of a step-by-step process, and I think that’s what really got people excited about Gandhianism, that there was a disciplined method that he had to offer.

Isaac: Dan said that the intellectual roots of the Danbury Prison Strike could be traced back to one specific place, a seminary.

McKanan: Union Seminary in New York was focal point for a lot of conservations for how issues of racial justice, economic justice and issues of war fit together. Union seminary, which is closely connected to Columbia University, is located just a few blocks away from Harlem. So, as Harlem flowered as the center, the intellectual center of the American black community, students at Union seminary were keenly aware of that. Union seminary was also the sight of some pretty intense debates about which flavor of social justice work made best sense.

Isaac: Just prior to American entry into the Second World War, when the United States had started to draft men into the army, a group of students began meeting at Union Seminary to discuss how to resist. As seminary students they were exempt from the draft, but they worried a lot about the morality of joining the military. Some decided that World War II was a Just War, and enlisted. Eight Union Seminary students so strongly opposed the war that they opted to go to prison.

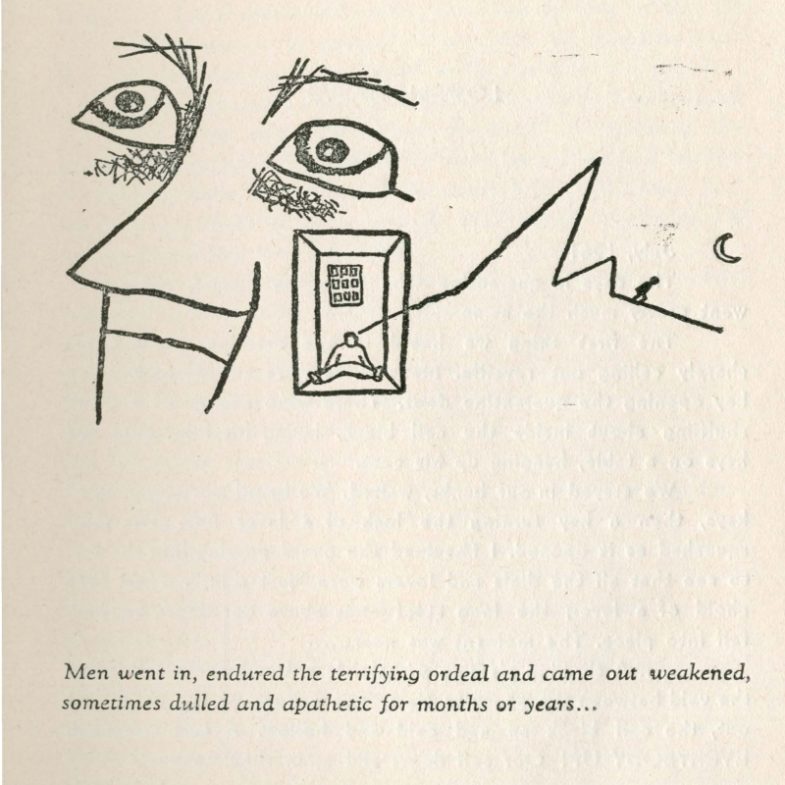

McKanan: White seminarians from relatively privileged backgrounds find themselves in Danbury prison, and they are asked to get into a whites only line, while the black prisoners are in a different lines for meals. So, Don Benedict, one of the eight, decides that he won’t get in that whites only line. He stands in the line for the black prisoners, and the prison guards say, “nope, sorry, you can’t be in this line, you have to be in this other line.” So, he and his friends talk, “what are we going to do about this?” They write letters, and for the entirety of the eight months they are in prison they are sending reports out to pacifist organizations and especially to organizations for mainline Protestant college students, describing in detail their discernment process, and describing in detail what they are experiencing. So, if you’re a Protestant college student in 1940 active in campus ministry on your particular campus you’re reading everything that happens to these eight young men.

And so, after Don is not allowed to get in the blacks only line for lunch he and his friends decide that on International Student Day they will refuse to participate in prison work, and they will engage in a hunger strike, or, a fast really. And the prison warden announces that everyone is the prison is going to punished for their action, trying to divide the non-political regular prisoners from these pacifist activists, who are trying to push the issue of racial segregation. As it happens- and this is in Don Benedict’s retelling of the story- the other prisoners weren’t willing to accept the warden’s version of what’s going on, and demanded that they hear from the students who were engaged in the fasting and the striking to find out, so you have a conversation that starts to spread throughout the prison.

Isaac: This prison strike didn’t achieve its goal, but almost three years later in 1943 another prison strike would. The 1943 strike drew on more than just these white pacifist activists. The largest group of interned objectors to war in Danbury at the time were Jehovah’s Witnesses, an interracial religious group that had few political concerns, but their objection to fighting had landed many of the men from the group in federal prison. By 1943 the Gandhian inspired COs were able to make common cause with the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who simply wanted the ability to worship and live together with their co-religionists. The weight of massive prisoner demand for desegregation, and the potential of negative publicity meant that the CO’s ultimately won, desegregating dining facilities in the prison. But for the victorious CO’s it was only a first step in a long campaign that would continue after they left prison.

McKanan: So, you have a number of people who come out of their World War II prison experience looking for other opportunities to use Gandhian methods to resist Jim Crow segregation. So people who had been shaped by that prison experience- whether it was because they went to prison or simply because the read about in their campus ministry newsletter, had their eyes opened, and got involved in new organizations like the Congress of Racial Equality, that would engage in sit-ins in the north. They would engage in civil disobedience at restaurants than on buses, with the Journey of Reconciliation, which brings some people who had been shaped by this phase of activism into a new way of resisting segregation. And all of that creates a community of people who care about racial justice, who think that Gandhian methods are the right way to bring about racial justice, who are primed to respond when a group of African-Americans in Montgomery, Alabama began the boycott to desegregate their buses in the deep south. Most of the people who participated in the Montgomery bus boycott did not have deep personal connections to the Congress of Racial Equality or to the segregation sit-ins that had been going on in the north, their activist tradition was in their churches and in the NAACP, which was very active in Montgomery. But when those folks took action, and were able to do it successfully in the deep south you have a lot of northern activists who had been waiting for something like that to happen, and this culminates in the Freedom Rides, later in the nineteen sixties.

Isaac: For many civil rights activists, their CO experience was a defining critical fact of their early biography. James Peck, who wrote the song that played earlier, took a leading role in the strike. When it finished, he declared, “It’s over, we’ve smashed them.” Peck would later take part in two campaigns to desegregate busing, the Journey of Reconciliation and the later more famous Freedom Rides. He endured beatings and arrests as part of his efforts.

Bayard Rustin, a key advisor of Martin Luther King, Jr., wasn’t at Danbury during the strike. But he corresponded with imprisoned COs who were striking, which inspired him to resist the draft. Rustin ultimately was sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky, where he organized CO’s to defy racial segregation there.

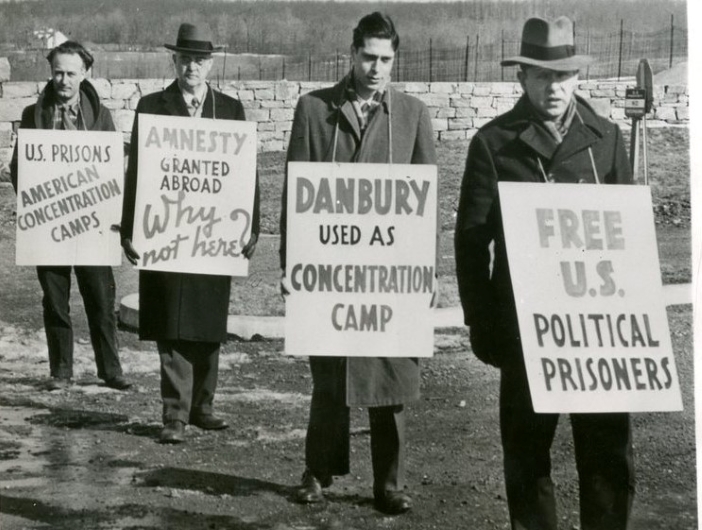

The history of Danbury prison, however, did not stop the minute the strike was successful. Even the conclusion of the Second World War did not mean COs were able to go home.

Lindenauer: This was also a site of a lot of protests post-World War II seeking amnesty for conscientious objectors. I’m Leslie Lindenauer, I’m a professor in the department of history and nonwestern cultures at Western Connecticut State University.

So people returned here because there were still COs imprisoned at Danbury for several years after World War II. But their protesting at that point- people protesting for amnesty for CO’s were mostly protesting at the White House, but they show up here periodically.

Isaac: During the Vietnam war objectors to war were once again housed at Danbury. Leslie says that now Danbury prison is mostly known around town not for the prison strike, but for a far more recent development.

Lindenauer: I know what pretty much everyone knows about Danbury prison, number one, which is that Orange is the New Black, though it’s set in New York state, Piper Kerman was incarcerated here. That she talks about listening to WXCI, which is the Western radio station while she was incarcerated at Danbury.

Isaac: Growing up, Connecticut schools focused a lot on telling me about the Civil Rights activism in South, but ignored the origins of much of that activism, which happened only a few miles from where I was in class. What happened at the Danbury prison shows that the struggle for Civil Rights is not simply a southern issue.