Sites of Memory

[00:00:03]

[00:00:07] Fountain Hughes My name is Fountain Hughes. I was born in Charlottesville, Virginia.

[00:00:14] Jalane Schmidt Fountain Hughes was an old man when he sat down for an interview with the Library of Congress researcher named Herman Norwood in 1949.

[00:00:23] Fountain Hughes My grandfather was 115 years old when he died. And now I am 100 and one year old.

[00:00:36] Jalane Schmidt Norwood is fascinated that Hughes had lived through the Civil War, which had taken place nearly 90 years before they sat down together.

[00:00:45] Norwood Do you remember much about the Civil War?

[00:00:48] Fountain Hughes No, I don't remember much about it.

[00:00:50] Norwood You were a little young, I guess

[00:00:54] Jalane Schmidt But he wasn't interested in talking about the war, nor was he was interested in talking about famous landmarks like Thomas Jefferson's Monticello estate or the University of Virginia that Jefferson founded. But there was another place he remembered. The place his mind returned to was Charlottesville's Court Square. All through the 18th and 19th century, it was the place where business was conducted, where a man like Jefferson and Madison and Monroe argued legal cases and where property was bought and sold, including human beings

[00:01:29] Fountain Hughes We were slaves. We belonged to people. They sold us like they'd sell horses or cows on the auction bench. Put you on the the bench, they bid on you and the same as bidding on cattle, you know.

[00:01:41] Norwood Was that in Charlotte or Charlottesville.

[00:01:43] Fountain Hughes That was in Charlottesville.

[00:01:43] Norwood Charlottesville, Virginia.

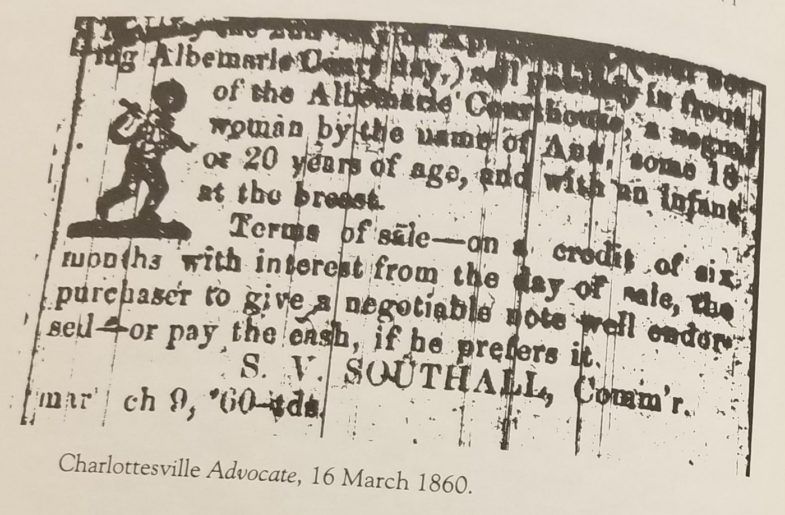

[00:01:46] Fountain Hughes They'd sell you to what they called a n------ trader, have a sale every month you know, at the courthouse

[00:01:59] Jalane Schmidt I'm Jalane Schmidt.

[00:02:00] Kurtis Schaeffer I'm Kurtis Schaeffer

[00:02:01] Martien Halvorson-Taylor and I'm Martin Halv0rson-Taylor. And this is Sacred & Profane. Today on the show, we're going to talk about how Charlottesville remembers that history with our colleague, Jalane Schmidt. Jalane took us on a tour of Charlottesville's Confederate monuments, which featured in an earlier episode. Since then, three of those monuments were removed from the land around Charlottesville's county courthouse. But just a few feet from where those statues stood is an unmarked patch of brick. The location of the auction block that fountain Hughes so vividly remembered.

[00:02:55] Jalane Schmidt I'm sitting here in downtown Charlottesville's Court Square at the corner of Park and Jefferson streets on a park bench in the shade and next to me is Myra Anderson. Myra, can you tell us why we're here? Tell us who you are. Tell us what this space means to you.

[00:03:15] Myra Anderson I am a Charlottesville native. I'm a mental health advocate and poet. And I'm also a descendant of the enslaved families of Monticello, the Hern family. And I'm here in Court Square, which is a place where six of my ancestors were sold in 1829 at the second estate sale of Thomas Jefferson. So I'm literally looking across the street at the very place that they were put on the auction block.

[00:03:58] Kurtis Schaeffer Myra's ancestors were sold to defray Thomas Jefferson's debts. They were among the hundreds of people enslaved at his Monticello plantation during his lifetime and some of the hundreds of people bought and sold in the shadow of the Albemarle County Courthouse in downtown Charlottesville.

[00:04:18] Jalane Schmidt In our last episode, we talked about how the Confederate statues that dominated Charlottesville's downtown were part of America's civil religion. It was these symbols and stories that helped define American identity and public memory.

[00:04:35] Martien Halvorson-Taylor As these statues come down, a new type of public memory is emerging in Charlottesville. Stories that reflect the lives of the majority of the people who lived in the surrounding county at the outbreak of the Civil War, stories that put names to the enslaved men, women and children who built Charlottesville's landmarks. These include the grounds of the University of Virginia and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and stories of their descendants who still live in Charlottesville today.

[00:05:19] Jalane Schmidt Myra and I went to Court Square on a quiet Saturday morning. But even on a quiet day, there were still plenty of people in the square and nearby parks, people walking their dogs. There was a couple getting married by the county sheriff on the courthouse lawn and a steady stream of people pausing in front of a small brick building just across from the courthouse itself.

[00:05:43] Jalane Schmidt So we're standing here right now in front of the number zero building and on the sidewalk here. Among all the buckets of flowers there used to be a do you remember Myra, how there used to be a plaque there in the sidewalk?

[00:05:57] Myra Anderson Yes, that you could barely see because you were walking over. Top of it is that we were talking about that was right there. I mean,

[00:06:06] Jalane Schmidt yeah, it's like no more than like one foot by one foot. I mean, you just, you know, if you walk by on the sidewalk, you wouldn't even see it because it's just set in the bricks, you know? And it said it said slave auction block on this site. Slaves were bought and sold.

[00:06:24] Martien Halvorson-Taylor The corner at Jefferson and Park Streets that has become an informal memorial to the hundreds of people sold in Court Square is just one of several sites where auctions took place. A few yards away is the former site of the Eagle Tavern.

[00:06:41] Jalane Schmidt the largest recorded sale of human beings in Charlottesville at one time took place here, and it was Thomas Jefferson's estate sale. You know, he died in 1826. Very much in debt as executor was his grandson, Thomas Randolph Jefferson, and the way of getting the estate out of debt was to sell its assets and part of its so-called property were human beings.

[00:07:09] Myra Anderson This is the place in 1829 right here where it's Jefferson's estate sold 33 enslaved people, and my ancestors were six of those 33. There was Davy Hern Jr. and then there was actually my grandfather, David Hern. There was Lily Hern, who is my sixth great aunt, and she and her husband also were sold to a professor at the University of Virginia. Her husband's name was Ben Snowden, and then there was Fanny Gillette Hern had already been sold in 1827 sale to a professor at UVA. And so the story goes that Fanny was convincing the people who owned her to come and purchase her husband, too. And that's exactly what happened.

[00:08:13] Jalane Schmidt Myra's ancestors weren't alone in fighting to stay together in 1852. Another enslaved woman in Albemarle County. Maria Perkins wrote to her husband. He, too was enslaved to a different master. Son had just been sold to yet another slaveholder in front of the county courthouse.

[00:08:38] Maria Perkins (reader) Dear husband, I write you a letter to let you know of my distress. My master has sold Albert to a trader on Monday Court Day. Myself and the other child is also for sale. I want to hear from you soon before the next court date. If you can, I want you to tell Dr. Hamilton or your master if either will buy me. I don't want to try to get me. They took me to the courthouse. A man by the name of Brady bought Albert, he is gone. They say he lives in Scottsdale. I'm quite heartsick. I am and ever will be your kind wife. Maria Perkins.

[00:09:32] Myra Anderson Just listening to that letter, it talks about desperation. It talks about despair. It talks about that. The Albert, I'm assuming is the young son has already been sold. Right. It's just it's words cannot like accurately express, like the feeling I get inside, just thinking about that. The one thing that kept them together, the love of family and to think all of that ended up on the auction block. I honestly think is one of the greatest atrocities, and we still haven't come to terms with that in a way that is open and transparent and speaks to the ugly past of what actually happened. We have yet to really unpack that.

[00:10:32] Kurtis Schaeffer Like Myra says, Charlottesville has been reluctant to unpack much of its history. It's been easier to disavow the Confederate monuments. After all, they represent just four years of the town's past.

[00:10:46] Jalane Schmidt It's been harder, however, to confront hundreds of years of slavery and systemic oppression of the black community. But there has been some change. Last year, the University of Virginia dedicated the memorial to enslaved laborers. Names of some of the hundreds of people who labored to build and run the university, including Myra's ancestors, are now engraved in a stone circle within sight of the university's famous rotunda. And Jefferson's former plantation, Monticello, has also taken steps. When Myra was growing up in Charlottesville, she remembers visiting Monticello on a school trip and touring the house. Slavery was never mentioned, even though Jefferson was one of the largest slaveholders in Virginia.

[00:11:35] Myra Anderson My grandmother told me when I was probably in late elementary school that our ancestors were enslaved at Monticello, and honestly, I did not believe her. And the reason the reason I didn't believe her is because we have visited Monticello in school and they never mentioned anything about enslaved. They used the term servants. I didn't think at that point that there were any enslaved people there. And then I thought if they were, surely my teacher would have told me that. And so what is grandmother? She's talking a little bit foolish.

[00:12:10] Jalane Schmidt In the years since, Monticello started the Getting Word Project. It's an attempt to contact descendants of the more than 600 people held in slavery at Monticello during Jefferson's lifetime and to document their family stories. Myra heard about the project in passing.

[00:12:28] Myra Anderson It was only in 2018 I was on a trip to Ghana. I went on the sister city delegation. At one point it was 56 of us. We were introducing ourselves and the historian from Monticello at the time, Niya Bates, was on the trip. And when she introduced herself, I went over to her and I was like, You know, I know there is like a descendants project at Monticello, and I wanted to know if you could get me connected to that because I know my family is connected. My grandmother told me and she was like, Well, who is your family? And I said the Hern family, and she says, "we've been looking for your family." So like, here we are, like 5000 miles away. And we just had this one serendipitous moment that changed my life. When we got back here to Charlottesville, she was like, "you know, there's been books written with your family information in it." And she gave me the titles of books. She connected me with the librarian at the Jefferson Library. And I began to to go up there and learn as much about my family as I could. I sometimes consider myself lucky in the sense that at least I know their names. You hear about individuals being sold and the only perhaps just a like a farmhand or something like this is...it makes the atrocity even greater because we will never know who those individuals are. And so I think there is an opportunity if there was such a space to even bring light to the people that we don't know and hold space for that as well.

[00:14:03] Martien Halvorson-Taylor We've talked about official memorials and what Myra is reminding us of is all of the informal memorials, the sites of memory, the stories of memory that literally bubble up. And you've done a lot of work, Jalane, on how to recontextualize the built memorials of the past or remove them. How do you navigate these sort of memorials and what? What are their futures?

[00:14:35] Jalane Schmidt Yeah. Well, I mean, that's the thing is that in Charlottesville, we love our public history, people are very passionate about it. And there's just a segment of the public that has become very insistent about memorializing especially the number zero building there, the former Benson Brothers building on the corner of Jefferson and Park streets, where that slave auction block was. You know, you go by there and several times a week there are fresh flowers that are there. You know, people are just...they just flock to it. When Maya and I were there, you know that Saturday morning, people were clearly seeking it out and coming there and taking pictures, you know? And at first, when it sprang up in February of 2020, the city, the public works department used to just clean it up. And they've just given up, you know, it's just so repeated and so insistent. And and it shows how sensitive public memory has has become around this specific place. I mean, it's one of many places, but this specific place, the Benson Brothers building as a sort of it's a sort of hallowed ground, you know, and not to be trivialized.

[00:15:43] Kurtis Schaeffer And now it's for sale.

[00:15:45] Jalane Schmidt I know exactly. Right, yeah, so so the place where human beings were monetized is now itself being monetized.

[00:15:53] Kurtis Schaeffer And here's the advertisement for the Benson Brothers building: "The best location in Court Square. This historic and unique property is ideal as an office for a legal, financial consulting or technology company, or it could be renovated and converted to a charming, historic urban residents. The property has several parking spaces and looks out onto the Albemarle County Courthouse. This is an opportunity to purchase or lease a one of a kind historic property on Court Square."

[00:16:25] Jalane Schmidt Yeah, it's definitely one of a kind. And, you know, the best location, you know, for what I guess is the question, and you know, there are a lot of members of the public were just indignant when they when they saw this one, local journalist Jordy Yeager tweeted out What's the going rate for a historically preserved site of human trafficking, bondage and violence in Charlottesville? Apparently, the bidding starts at one million $350000.

[00:16:53] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Yeah. And I guess the point is that the meaning making and the memory making is not going to stop.

[00:17:00] Jalane Schmidt Yeah, I think that's I think that's going to go on. The public repudiation that there has been over the past several years of these Confederate monuments and the frustration with the fact that they the monuments just stayed, you know, for years beyond their welcome. Think that just kind of got channeled toward wresting control over these other sites, you know, like like with slave auction block.

[00:17:24] Kurtis Schaeffer So, Jalane, in the case of the Confederate monuments, it was fairly obvious why we should talk about them in terms of religion. The plinths, for instance, have angels and religious symbolism carved on them. They were installed with clergy attending and giving speeches and blessings. In the case of the auction block, what is the value of talking about religion?

[00:17:45] Jalane Schmidt Yeah. Well, I think, you know, like you mentioned with the Confederate monuments, I mean, it's officially on public land. It is maintained by the city with our tax dollars, you know, and you know, there's this officialdom to it. We can call, you know, civil religion is what it is. You know, public schoolchildren are brought there on field trips, you know, etc. And with the slave auction block, it's definitely it's more of a kind of bubbling up, you know, kind of popular sentiment. This is not something that's been endorsed by the city. I mean, like I mentioned, you know, at first, the City Public Works Department kept clearing away, you know, the flowers and mementos that were left. But I think, you know, people are investing it with meaning recovering, you know, the memory, you know, of the people who were sold there, pulling them further into our community of memory. Let's, let's put it that way.

[00:18:38] Martien Halvorson-Taylor One of the interesting things about these memorials is not simply that they're unofficial, but it's what what people are actually doing. It's how they're actually making meaning out of their renewed sense of their long history, and that people are investing it with ritual in the same way that you would visit a grave and put down flowers. They want to mark something as as significant. And that's religion.

[00:19:12] Jalane Schmidt That's right, and especially, you know, as the past for the past three years, the community's been holding slave auction block vigils, you know, kind of on the eve of the Liberation and Freedom Day commemorations, you know, every year in early March. And so, yeah, and so the community has been drawn as a group and listening to the very stories that we've just been recounting here. You know, and so this is this has been kind of radiating out into the community, and I think it's, you know, kind of planted a different sort of consciousness of the community's history and people have become, you know, more insistent, you know, on on on claiming this. And there's just really a sense going forward that it should be the descendants that should have input. And, you know, a role in steering this discussion.

[00:20:10] Myra Anderson So I think the very thing that's starting to happen and I hope that it continues to happen is making seats lots of them at the table for descendants, people who have been most affected by those atrocities of the past. And so I think if that is the focus as we look at how to commemorate, how to memorialize and what to do in these spaces and if we do that, whatever direction and whatever the outcome is, is going to be good because in a way that in and of itself is redressing something that was not a part of the past by bringing voice to that. That's excellent.

[00:21:07] Kurtis Schaeffer Sacred & Profane was produced for the Religion, Race & Democracy lab at the University of Virginia. Our senior producer is Emily Gadek. Our program manager is Ashley Duffalo. Today's show was reported by Jalane Schmidt. Our guest was Myra Andersen. Our reader was Angie Chatman.

[00:21:29] Martien Halvorson-Taylor Music for this episode comes from Blue Dot Sessions. You can find out more about our work at Religion Lab Dot Virginia Dot Edu. Or by following us on Twitter at the Religion Lab.

The Confederate monuments around Charlottesville’s county courthouse have all been removed, and a new kind of public memory is emerging in Court Square. The streets around the courthouse were the site of hundreds of slave auctions over Charlottesville’s history.

The descendants of the people who were bought and sold in the square are at the center of a movement to bring their stories to the forefront—in essence, to create a new civil religion. Our colleague Jalane Schmidt and descendant Myra Anderson met in Court Square to discuss how the memory of the humans bought and sold in the square is changing Court Square itself, and changing our understanding of Charlottesville’s past.

How to cite this piece:

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K. (Presenters), Schmidt, J. (Reporter), Anderson, M. (Guest) & Gadek, E. (Producer), “Sites of Memory” Sacred & Profane (2021, October 27).

Related Content

The Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia deals with a fundamental problem in the history of slavery and colonialism: how to commemorate the lives of people whose names, as a result of the violent institution of slavery, were not kept for history? How to represent both their presence and the erasure of that presence in the shape of the Memorial? Lab Fellow Sergio Manuel Silva explores these questions, and the connections he sees between the Memorial and the poetry of Pablo Neruda.

Additional Reading

“Getting Word: African American Oral History Project.” Monticello (online). Accessed October 26, 2021, https://www.monticello.org/getting-word.

“Maria Perkins letter.” Wikipedia. August 12, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Perkins_letter.

“Photo essay: Slave auction block vigil.” Charlottesville Tomorrow online. March 10, 2020. https://www.cvilletomorrow.org/articles/photo-essay-slave-auction-block-vigil/.

“President’s Commission on Slavery and the University: Report to President Teresa A. Sullivan.” University of Virginia. PDF file. July, 2018. Accessed October 28, 2021, https://slavery.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/PCSU-Report-FINAL_July-2018.pdf

“The 1827 Slave Auction at Monticello.” Monticello (online). Accessed October 26, 2021, https://www.monticello.org/slaveauction/.

“The Hern Family.” Monticello (online). Accessed October 26, 2021, https://www.monticello.org/slavery/paradox-of-liberty/enslaved-families-of-monticello/the-hern-family/.

Douglas, Andrea, and Jalane Schmidt . Marked by These Monuments, WTJU 91.9 FM, www.thesemonuments.org/.

Garrett, Alexander, “Account of Sale of Slaves from Thomas Jefferson’s Estate.” Monticello (online). January 1, 1829. https://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/2340.

Halvorson-Taylor, M., Schaeffer K. (Presenters), Schmidt, J. (Guest), & Gadek, E. (Producer), “American Idols.” Sacred & Profane (2020, July 20). https://religionlab.virginia.edu/podcast/american-idols/

Schmidt, Jalane, “Humans Were Sold Here: Remembering Slave Auctions in Charlottesville’s Court Square.” Medium.com. March 2, 2020. https://medium.com/@JalaneSchmidt/humans-were-sold-here-e326e28b03ad.

Additional Credits

Special thanks to voice actor Angie Chatman, and to our guest Myra Anderson.