Three years ago, I was sitting at my desk in Sheffield, England, pouring over the week’s reading for my Cold War history class. As I read through the article, a single line caught my attention: ‘the Jackson Vanik amendment to the US-Soviet trade bill was passed in 1974 after a national campaign by the Soviet Jewry Movement’. A social movement? A Jewish social movement? A Jewish, Cold War social movement? This was right up my street. How had I not heard of this before? Like any dutiful undergraduate, I turned immediately to Wikipedia. That’s when I discovered Jacob Birnbaum, and the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. I was hooked. That single line led me to my master’s dissertation, my PhD, and this project with the Religion, Race and Democracy Lab.

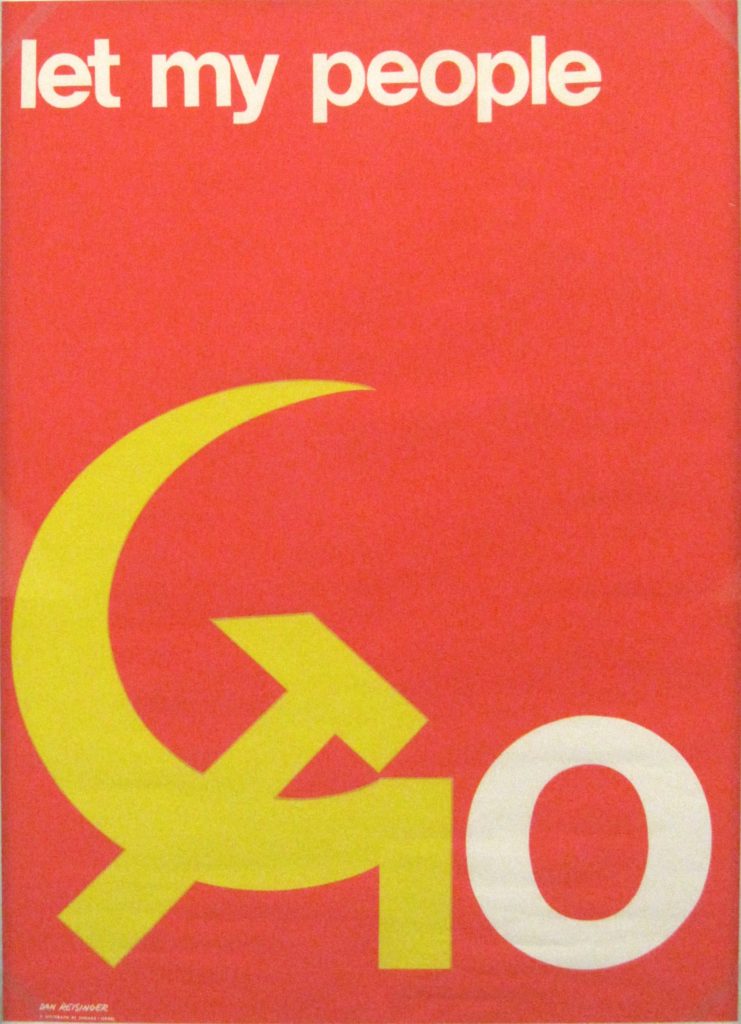

Very quickly after that first day, I realized something—it wasn’t just me who hadn’t heard of the Soviet Jewry Movement. I got used to blank stares from friends and acquaintances. By the time I got to the University of Cambridge for my master’s degree, I had perfected an elevator pitch for any situation: ‘I study the Soviet Jewry Movement, which was an international campaign to advocate for the human rights of Soviet Jews, particularly the right to emigrate’. I told everyone who would listen about Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. I told them that Jacob Birnbaum had founded the organization in 1964, the first dedicated Soviet Jewry movement group in the United States. I told them that his vision was a vibrant, youth-led organization bringing about real political change on an international level, and that for decades, SSSJ kept Soviet Jews in the news with their publicity stunts. I’d show my friends the photographs I’d collected from my archive trips—SSSJ activists dressed as gulag prisoners, baking mocking cakes, holding sit ins.

And I began to wonder, why hadn’t everyone heard of the movement? After all, it seemed to have succeeded in its goal of free emigration for Soviet Jews. It had given Jewish Americans invaluable political experience, it had raised their self confidence, it had brought them together, and then it had been forgotten. No one knew the names of these pioneering activists who had devoted thousands of hours, years, decades even, of their lives to the cause of Soviet Jewry. No one knew the names of the Soviet Jews themselves, the refuseniks who had suffered harassment, discrimination and even imprisonment in order to gain the right to emigrate for themselves and their fellow Soviet Jews. Why not?

This project hopes to help change that. I want to showcase the work of Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry in the vital first ten years of the movement. I want to show how SSSJ’s pioneering activism reflected a rapidly changing world, how it contributed to a worldwide movement. Most of all, I want to tell the story of how the vision of one man and the hard work of a handful helped to galvanize thousands and transform the lives of millions. The story of SSSJ and the wider Soviet Jewry Movement is a vital part of history—Jewish history, American history, and Cold War history. This project hopes to go some way towards making sure it takes its rightful place in this history. Maybe then, one day, I won’t need that elevator pitch.

To view the project, click here.

Get Involved

Learn about forthcoming podcast episodes, newly published projects, research opportunities, public events, and more.

Potential Students